Architectural education has a transforming effect on those who pass through the years of its unique approach to learning. Consider the following:

You’re 18 years old. Did pretty well in high school. Your general learning skills are considered advanced by current standards. You’ve crammed for the occasional final, but you’ve always successfully structured school, extracurricular activities, a so-called social life and maybe a part-time job.

Your future is bright.

Then, during the first day, week or month of architecture school, you are told in one way or another that if you’ve chosen architecture because you want to make money (read, a living), you’re sadly mistaken. A subtler, though more insidious, lesson is one about the worth of your time. These two signals are inextricably linked.

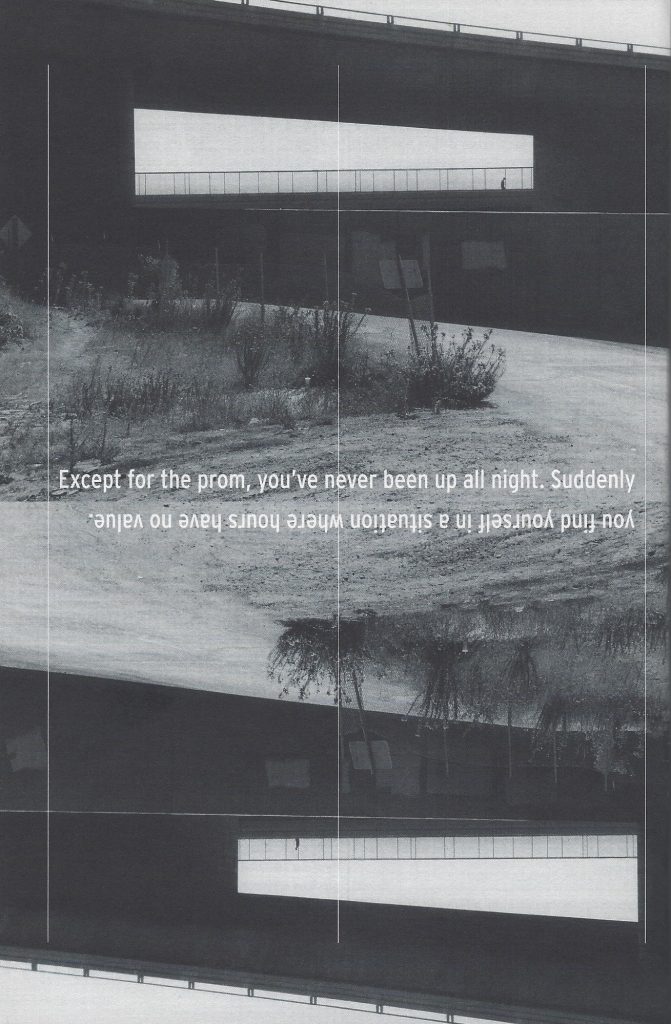

Except for the prom, you’ve never been up all night and certainly not for work or school. Suddenly you find yourself in a situation where hours have no value, yet there are never enough of them. Your time-management habits, which served you well for the first part of your life, are now useless.

The messages (all especially suspect in light of current thinking about how humans work and thrive) are clear. Good design necessitates countless hours. The more time spent the better the result. Your time is of secondary importance to the product. Total devotion is a badge of honor. Classmates who attempt to maintain some form of balance in their lives are slackers.

After graduating, you have poor to no time-management abilities and even less respect for your own time. Still, we practitioners expect you to take seriously the schedules and time allotments we’ve established, based on our contracts and fees. And if the job takes more time than is budgeted? No problem. We’ll (flirting with labor-law noncompliance) put you on salary.

The attitude toward time that students adopt is (or appears to be) profitable to the profession. Every year the schools deliver thousands of intelligent, talented and skilled graduates who are willing to work long hours for poor wages. (The dichotomy of healthy egos and low self-esteem doing battle within the graduate is a subject worthy of closer study.)

Ultimately, the discounting of time reduces the quality of service a profession can deliver. Architectural services are considered more and more of a commodity, and society increasingly insists on both a “deal” and flawless performance. The students who got the message that it’s OK to routinely give away services are those who will, as practitioners, do just that.

When business-school texts have titles like Blur and Faster, it’s time to question what we instill during the early years of the making of architects.

Author Michael Hricak, FAIA, AIACC first vice president/president-elect, has taught and practiced in southern California for the past 20 years.

Photo illustration by Bob Aufuldish.

Originally published in early 2000, in arcCA 00.1, “Zoning Time.”