Founded in 1959, the University of California, San Diego sits on 1,200 acres of prime real estate near La Jolla in northern San Diego. The campus has developed over five-and-a-half-million square feet of buildings in the last twenty-one years, including works by Moshe Safdie, Bohlin Cywinski Jackson, Michael Rotondi, Antoine Predock, and many others. For the most part, the campus has relied on delivering projects the traditional way, hiring architects and bidding out projects to qualified builders.

Unlike other schools in the UC system, UCSD has not had much recent history utilizing the design/build delivery method. An attempt to build housing through a developer design/build process in 2000 ended in disappointment when the University and the chosen developer couldn’t come to financial terms due to accounting rules changes.

In 2003, with construction costs in a rapid and unpredictable escalation and facing a dire need to provide student housing on-campus, the university—led by Campus Architect Boone Hellmann, FAIA, and Director of Housing and Dining Mark Cunningham—set about to try the design/build process once again. To the University’s credit, they sought to do so in a manner that provided the benefits of design/build while making design as important a consideration as costs. Doing so required a method different from that typically used, but upon reflection it is a technique that others would be wise to emulate.

Instead of utilizing the typical bridging documents method (in which the owner hires an architect to take a design through design development before turning it over to the design/build team to complete the construction documents and the building itself), UCSD began by hiring Brailsford Dunleavy with Hanbury Evans Wright Vlattas to perform programming and site analysis in preparation for a true design/build competition to take place. The University short-listed four design/build teams, placing great emphasis on the design team compositions. The teams were Bovis Lend Lease/Harper Construction/AVRP; Suffolk/Sasaki; Facilities Group/Ratcliff; and Sundt Construction/Studio E Architects/ MVEI. Each team was given two and a half months to prepare a proposal.

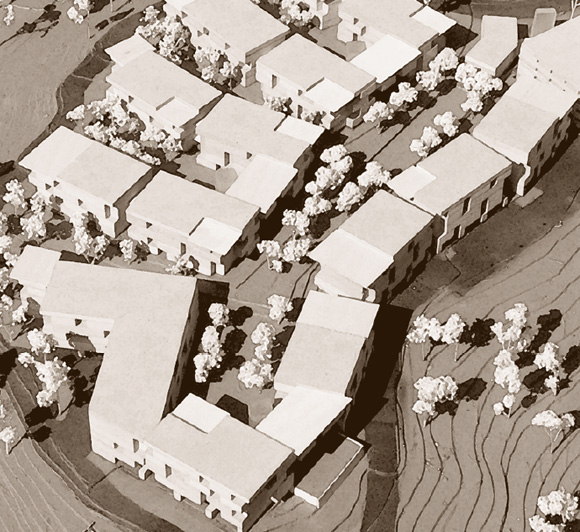

Rather than presenting the design/build teams with design preferences and asking “How cheaply can you build it?” the university gave the teams a budget and asked, “What is the best building you can make?” Each team was also given a sizable stipend for the costs to prepare the submittal. The resulting design and cost proposals were presented to a broadly based selection committee that included students, faculty, housing administration staff, and the design review board for the university. This committee selected the team of Sundt Construction/ Studio E Architects/MVEI. The 800- bed graduate student housing project—now called One Miramar—is currently under construction on the east campus of the university.

Some important outcomes are worth noting:

- The competition was focused on adding value instead of cutting costs. The positive direction of the design deliberations was a refreshing break from the negative premise of most design/build situations. The team was always asking “How can this be done better?” instead of “How do we do things for less?”

- The university was presented four well-crafted and thoughtfully presented schemes from which to choose. Each team made significantly different decisions, which led to very different final schemes. A true choice was available. Importantly, the university’s mindset turned from protecting early design concepts from cost limitations (as is so often the case with design/build) to an open dialogue about what was best for the university, given the available funds.

- A broad and inclusive constituency participated in the process, making for smooth sailing through the large number of reviewing entities at the university. Time, money, and goodwill were all preserved.

- The entire design/build team felt that the process was fairer, gave them control of the outcomes, and produced much better results. Importantly, the teams that did not prevail were compensated for their time.

As the design/build method becomes an increasingly preferred project delivery method, owners—whether they are institutions or private interests—could look to the UCSD model for getting superior results for the expected price in an environment that emphasizes a team approach.

Author Eric Naslund, FAIA, is a principal at Studio E Architects in San Diego. He is the past chair of the AIACC Design Awards Program and currently serves on the editorial board of arcCA. He is an adjunct faculty member at Woodbury University in San Diego.

Originally published 4th quarter 2006 in arcCA 06.4, “The UCs.”