“To a considerable extent, the problem of water in Southern California is a cultural problem. By this I mean that newcomers to the region, who have always made up a majority of the population, have never understood the crucial importance of water. Crossing the desert, they arrive in an irrigated paradise in which almost anything can be grown with a quickness and abundance that cannot be equaled by any other region in America. There does not seem to be a water problem. Nor are they told there is such a problem, for Southern California has always been extremely reluctant to discuss its basic weakness.” —Carey McWilliams (1946)

The freeway, the most famous symbol of Los Angeles, hovers over the landscape like the aqueduct system of ancient Rome. In contrast to the freeway, the water system of Los Angeles, which is much older and fundamentally more critical to its existence, is not as well known. One key reason is that the freeway is a public space and the water aqueduct is not. Daily, thousands of drivers keep their eye on the road and their ear to the radio, listening for SIG ALERTS, warnings of accidents ahead on the freeway. The ritual of the freeway is an everyday activity for residents of Los Angeles. The consumption of water is also an everyday ritual, but one which has been removed from our daily consciousness. This loss of consciousness is primarily due to the removal of the aqueduct from public sight. The ritual of water is no longer a public activity like commuting.

Los Angeles is an excellent example of a man-made desert oasis. Its present day physical form, however — like that of Phoenix, San Diego or other cities in the American Southwest — does not effectively celebrate the water system that nurtures its existence. Most residents thoughtlessly assume that their garden paradise merely comes from “turning on the tap.” In reality, a gigantic system of aqueducts, pumps, reservoirs, canals, and pipes delivers water from 500 miles away. To the average person’s perception of the city, this labyrinth remains hidden from view, except when he receives the monthly water bill or when he has to vote on water-related bond issues. Here, we… will explore the possibilities of externalizing the hidden water aqueduct system into a set of public spaces, activities, and monuments. Potentially, these new public spaces could be the articulated intermediate scale of urban spaces now missing from the Los Angeles landscape. New and existing developments can begin to infill and reorient themselves to the water places, rather than to the scale of the home or freeway.

Using the water aqueduct system as a test case, the goal of our design is to create a set of specific urban sources in and around Los Angeles, which will simultaneously provide utilitarian service, spatial clarity, and ritual places which celebrate a city created from water and sand. The method for this search we can call the design scenario — a process by which statements of policy are translated into three-dimensional architectural or city building programs.

Our method takes the statements of policy and poses the question: What if the information were expressed as architectural spaces or public monuments? The results of this process will generate two types of information. From the first, we can begin to see the effect a policy has upon the physical structure of a place. From the second, we can identify a spatial vocabulary. The following design scenarios look at the potential ritual places that can be created to celebrate both the spiritual and the utilitarian relationship of the city to its water system.

The First Ritual: The Point of Intake

The aqueduct begins hundreds of miles away from the city boundaries. At the Point of Intake, water is pooled from the natural watercourses into holding channels. At one end, the large pumps of the aqueduct lift station draw water up out of the pool, into the pipes of the aqueduct, and on to the distant city. At this point of transference, the water leaves the wilderness, or rural state, and enters the geometry of the city. To many, the lift station can be seen as the gateway to the city. To others, it is the outermost tentacle of the city as it stretches into the countryside.

The lift station, or Point of Intake, also symbolizes the battle for control of water resources, in which there are two participating parties. The first is composed of those who feel they have control over the water because of riparian rights. Since they own land from which the water originates, they feel that they should be in control of its future. The other party usually lives outside the area of the water’s origins and argues that an area’s water resources should not be limited and controlled by the few who own the land at its source. The water should be put to maximum use. They claim the need for appropriation rights. Two hundred years of litigation, legislation, and emotional arguments have been generated by this conflict over the control of limited water resources. This argument is rooted in the historic American conflict between rural virtue and urban intellectualism.

In order to ensure that no other remote region would face the fate of the Owens Valley, the State Legislature passed the County of Origin law in 1931, prohibiting the draining of one area’s water in order to supply other areas. This law helps small counties stop larger municipalities from looting local water resources.

In interpreting the law, the Point of Intake can be seen as the middle ground of the debate. It is proposed that a line be drawn between the intake lift station and the water pool of the natural water system, on which a building called the Basilica of Origin will reside. From this point, the basilica mediates between the values of the rural and wilderness landscapes and the geometric aqueduct lines of city, which terminate here.

In the Basilica of Origin there would be two icons representing the two sides of the water debate: those of the city and those of the county of origin. The basilica would create a place for the debates about balancing water supplies. It would be the formal space where the process of deciding the amount of water entitlement would take place annually.

Each year, lawyers, officials, and citizens from both sides would gather at the Basilica of Origin and act out the ritual of balancing the area’s water resources. This Act of Entitlement would be debated and recorded within the Basilica of Origin at each aqueduct. These basilicas would be created at the Delta, the Colorado River, and the Owens Valley, and each would represent the debate particular to that area of origin.

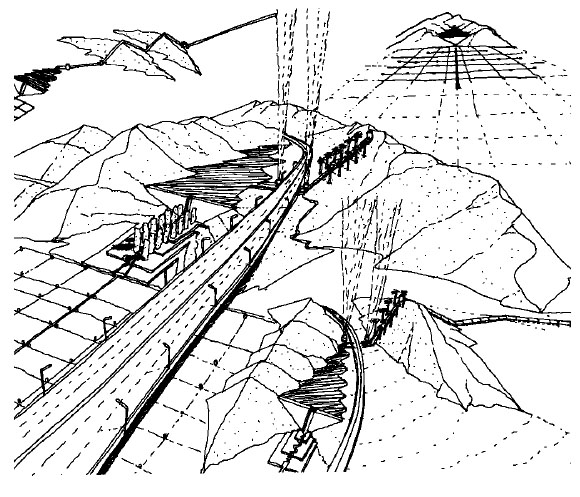

The Second Ritual: Lines of Transport

As it leaves the Point of Intake, tunnels, canals, conduits, and siphons carry the water across the dry landscape of the Southwest. These Lines of Transport tell the story of the land they traverse — a dry landscape marked by broad, open valleys, which lie between high, rocky mountains. The lines of transport zigzag across the desert floor and at times lift their cargo up and over rocky routes. These are the same routes taken by early settlers; today they are followed by travelers on the freeways that parallel the water system. These Lines of Transport act as ritual passageways from the open land and its ridges to the garden cities of Southern California.

The Lines of Transport unleash their power onto the landscape, a power that has been contained and withheld from the parched land it has just passed over. Each line is unique in its technology, its historical moment of construction, and the terrain it traverses. With its own rite of passage, each is perceived differently by the participants of the passage. To some, the Owens Valley Aqueduct represents a period of ruthless political exploitation. To some, the Colorado River Aqueduct represents the collective work spirit of the WPA. Finally, there is the California Aqueduct, which, to those of Northern California, represents the power and the insatiable thirst of the southern part of the state. Whatever the image, lines of transport act collectively as fingers extending the city into the distance, carrying with it the image and characteristics of that city. The symbolic functions of the City Fingers are to demarcate the distance and passage of time across the landscape and to inform the traveler of the past and present effect of the city upon the land, by creating a three-dimensional time line.

This scheme can be realized by visually externalizing the system on the land. During the day, at the bases of these ridges, the lift station can be landscaped with compact stands of trees, creating an oasis that demonstrates the life-giving power of the cargo carried in the lines. At night, when the drive across the landscape can be quite monotonous, the lift station can be lighted to create a focal point in the darkened landscape. The traveler counts off the illuminated ridges, assuring himself, “Only a few more before I get home.” It is a point on the horizon, marking time and distance and extending a fragment of the city into the desert. Thus, the monotonous landscape takes on meaning and texture.

The Third Ritual: Pools of Collection

Each aqueduct delivers its water to a reservoir. Like the water cisterns and fountains of Rome, which collected, stored, and distributed the water from the aqueducts, the Los Angeles reservoirs can represent both urban-entry landmarks and neighborhood fountains.

Located at the outer edge of the city, reservoir pools perform a utilitarian function by distributing the aqueduct’s water to the homes and gardens of the city. They also represent a transition from the linear aqueduct axis of the Lines of Transport to the spreading grid of the distribution system. A transition from the open, expansive scale of the surrounding mountains and desert to the more articulated individual scale of the irrigated city — from wilderness to civilization. Paralleling the terminus reservoir, the major interstate freeways breach the surrounding mountain walls of Southern California and Los Angeles. At this point, where water and traveler pass into the garden, the terminus pool can be developed into a formal entry space. This pool would be emblematic of both the land it is entering and the journey taken to get there.

Like the previous two rituals, these junctures can celebrate each aqueduct differently by representing the unique qualities of the particular system they serve — for instance, their geographic and historical origins. To the east of the city, the Colorado River Aqueduct greets those who have just crossed the desert. To the north, the terminus pool can be formed to greet the traveler who has traversed the mountain pass from the agricultural grid of the San Joaquin Valley. Finally, the terminus pool represents a potential gateway to the presently inarticulated sprawl of Southern California cities.

Spread out over the landscape of the city are Pools of Collection which could articulate distinctly different areas in the environment. As part of the distribution system, each terminus pool passes water into a series of smaller distribution reservoirs. These Pools of Collection are interrelated as parts of a larger distribution system, yet each should be distinct. Physically, they could be seen as landmarks, perhaps as super-scaled fountains like their antecedents in ancient Rome.

The Fourth Ritual: The Grid of Distribution

Fed by the Pools of Collection, the Grid of Distribution transports water to the individual consumer. It further reduces the scale, breaking down into a fine-grained complex of pipes and pumping stations that bring water to each house and garden.

Los Angeles and its environs are created by three overlapping grid systems: one from the Owens Valley Aqueduct, one from the Colorado River Aqueduct, and another from the California Aqueduct. Each is operated by a separate agency, but they are tied together to provide supplementary water as needed. Historically, city development has responded to the grid pattern of each system. At the smaller scales, growth has clustered around the major supply lines of the distribution system. Field patterns of agriculture have become large blocks of residential neighborhoods. At a larger scale, the shape of the cities of Southern California has followed each aqueduct system. The Owens Valley Aqueduct system caused the city of Los Angeles to extend northward from the original pueblo site rather than to the coastline in the west. The Colorado River Aqueduct allowed development to fill in the valley extending from the coastline on the western edge and eastward to Riverside. Rather than follow the Jeffersonian or Spanish grid, the city of Los Angeles and other cities of Southern California follow the Grid of Distribution pattern of irrigation and water distribution.

The Grid of Distribution is the lifeblood of the city. It could be said to represent the dialogue between the natural environment and its man-made settlements. To make its importance evident, Water Parks could be placed throughout Los Angeles and other communities to commemorate the rapport between man’s irrigation system and the ecology of Southern California. Each park would have three functions. The first would be to exhibit the wise utilization of water in a dry climate. The second would be to commemorate the bringing of water to the specific neighborhood. The design of each water park would reflect the origin of its water, such as the Colorado River, for example. The third function of the Water Park would be that of civic landmark. Each park would be site-specific and at the same time regionally tied, thus giving further definition of space to the Southern California plain, devoted not just to the domestic landscape, but to one of community.

The Fifth Ritual: The Private Spring

The homes and gardens on the grid plan of the San Fernando Valley sit like private oases. Faucets, sprinklers, appliances, and other fixtures provide pleasure, life-sustaining fluid, and cleanliness, with minimum inconvenience to the individual. Even in the arid climate, water to quench one’s thirst is never far away. The city is made up of millions of these Private Springs, each catering to individual ritual patterns.

While bathing in a household spring, there is little to remind one of the water’s sources. Actually, the faucet and water fixtures can be seen not only as utilitarian conveniences, but as connections to the community and to the distant landscapes at the end of the water aqueduct. Water in Beverly Hills is actually drawn from the Colorado River or the San Joaquin Delta. Across the street in West Hollywood, the tap water comes from the Owens Valley.

Domestic habits tie into the whole system of water rituals from the Point of Intake down to the individual faucet tap. Therefore, the design of the individual spring could reflect, through its image and usage patterns, the form and significance of the larger aqueduct system. The citizen is reminded daily of his debt to the entire water system. The Private Spring can achieve these ends by:

- Shaping the home and garden into patterns reminiscent of the components of the water system.

- Redesigning water usage fixtures to recall the origin of the water sources, such as a sink shaped like the delta reservoir of the Colorado River.

- Re-adapting the garden to plant material and patterns that utilize and represent irrigation techniques. The Private Spring terminates a long line of water transportation and thus, in many ways, is a representation of all the issues and physical patterns of the water system. If the Private Spring is designed properly, it can be a source within the city from which residents can reflect on the balance of water usage in their city in relation to other rural and urban areas.

Conclusion: Urban Places

The Pools of Collection, the Basilica of Origin, and other points of ritual along the water aqueduct system provide just a few examples of possible public activities that can be associated with the water system in Los Angeles. It is hoped that the design alternatives in this article will stimulate interest in the potential of developing urban places in the arid western city.

These design exercises emphasize that each aqueduct is part of a unique system, constructed to carry out the same tasks: the transportation and distribution of water. Each system must convey water a long distance from its source and also represent its historical and geographical origins. It is this collision between the utility of water transport and its contextual response that creates a set of structures that are simultaneously universal in principle and specific in response to locale. For example, each aqueduct might have a Basilica of Origin, but the articulation of that building would be different for the California Aqueduct than for the Colorado Aqueduct, since the former has its source in the lush river delta, and the latter is located on the edge of the desert.

The aqueduct system of Los Angeles… and the five ritual sections of the water celebration are design elements that provide inspiration for the future planning and shaping of the city and its architecture in the western oasis of Southern California. This exploration, which is not typically part of the architect’s repertoire, redirects traditional elements of architecture into new relationships. The West is a gigantic unyielding landscape: it should be used as an architectural context from which to develop the future shape of the city.

Author William R. Morrish, a California native, is the Elwood R. Quesada Professor of Architecture, Landscape Architecture, and Urban and Environmental Planning at the University of Virginia. He was previously founding director of the Design Center for American Urban Landscape at the University of Minnesota, where he created a nationally recognized “think tank” for professionals, academics, and civic leaders on issues of metropolitan urban design. In 1994, the New York Times hailed Morrish and his late wife, Catherine Brown, as “the most valuable thinkers in urbanism today.” This excerpt from “Urban Spring: Formalizing the Water System of Los Angeles,” originally published in Modulus (The University of Virginia Architecture Journal), no. 17, 1984, is reprinted by permission of the author and publisher.

Originally published 4th quarter 2001, in arcCA 01.4, “H2O CA.”