Walter Gropius was a prefabrication enthusiast. As early as 1910, while employed by Peter Behrens to intern and assist on various AEG projects, Gropius independently invented a system for prefabrication and, it is rumored, presented it to the AEG officials without the permission of Behrens. Behrens immediately dismissed the precocious young Gropius and altogether rejected Gropius’s prefabrication system. But Walter Gropius dung to his dream and tenaciously developed several versions while at the helm of the Bauhaus, while holed up in England during the rise of Nazi Germany, and upon arrival in the United States immediately before the outbreak of WWII. In America, Gropius frequently spoke to members of the architecture profession and building industry, society dames, and art institutes of the need for construction industries to partner with architects and home-sellers to develop a comprehensive nationwide system of building based on prefabrication.

Repeatedly, he prophesied,

On account of an extremely ramified integration, all the competing building industries will come to agree upon a reduced number of standard sizes for component parts of building. The designer and builder would then have at their disposal, say, a box of bricks to play with for adults, offering an infinite variety of such component parts for building which would be interchangeable.

Finally, in 1942, Gropius was given his chance to develop and implement a prefabricated housing system with the General Panel Corporation. It turned out, however, that prefabrication was, and is, not so infinite.

It seems rather natural that a person who ran the Bauhaus at the apex of its engagement with the machine, who designed cars and trains, and who preached a platform of synthesis between art and technology would be enamored with the promise of prefabrication. This theme developed over the years, beginning with his 1910 proposal, to his research into standardized “serial houses” at the Bauhaus in 1921, the Toerten Housing scheme of 1925, the prefabricated dwelling for the Stuttgart Weissenhofsiedlungen of 1927, the Hirsch-Kupfer copper prototype houses of 1931, and finally to the “Packaged House” for the General Panel Corporation. In each case, Gropius advocated the use of panels-made from steel, then copper, then wood- that would be manufactured in the factory, delivered by truck or train, and assembled into a house (or other small building) on the si te. He quickly gravitated to the 4’x8′ panel size, for ease of transportation (two can fit side-by-side on a flat-bed truck and still stay within the width of the standard highway or road) and because he envisioned a strong integration with builders and manufacturers, who were, by the 192os, adopting a 4-inch to 4-foot industry standard.

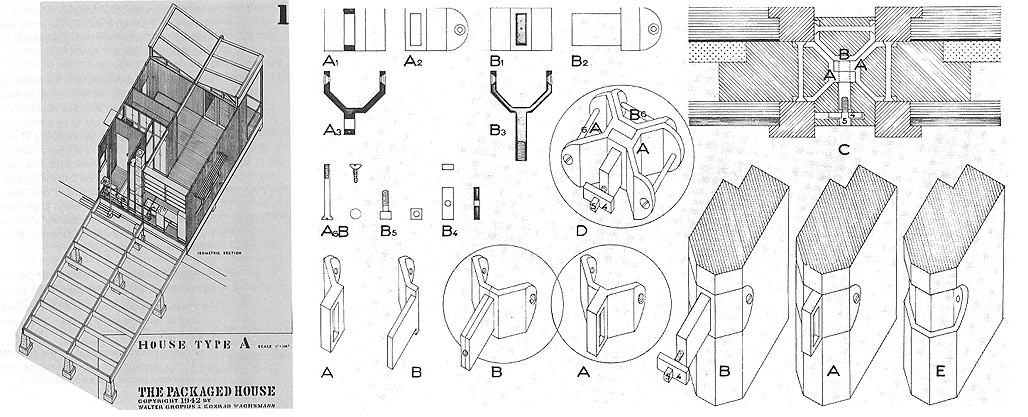

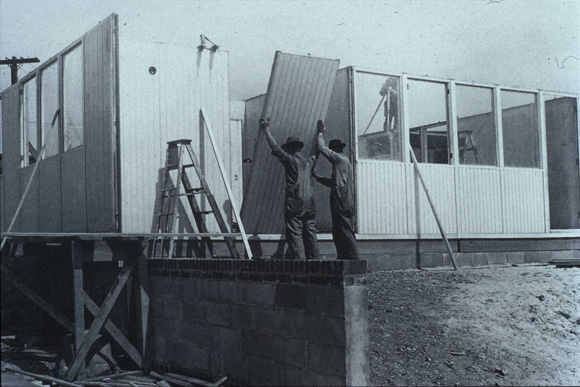

For the General Panel Corporation, Gropius teamed with Konrad Wachsmann, an engineer and designer and a fellow émigré, to develop a complete panel system. The “Packaged House” was to employ ten panel types. Some panels had cut-outs for windows, some could be used as doors, others could be used for walls, floors, or ceilings. The adaptability and flexibility of the panels depended on the ingenious invention of the “wedge connector.” The wedge connector was a small y-shaped channel piece made from a single metal die that could be fitted to other connectors on the same bolt. By inserting the panel edges into the wedge connectors, the panels could be connected side-by-side or at right angles to each other on either the short or long side. The effect, as envisioned by Wachsmann, was that the panels could be deployed in any three· dimensional direction, eliminating the need for any other construction system.

Gropius was against “total prefabrication” as too limiting. He recognized that formal variation is an architectural necessity; that it is what separates trailers, manufactured homes, and other mass-produced buildings from “architecture.” Instead, he turned to the prefabrication of the part, rather than the whole, at a very early stage. The guiding principle, he stated, was “the greatest possible standardization with the greatest possible variation in form.” Panels were a reasonable standardized component, and the wedge connector a perfect means for allowing variation without complicating the system. Restating his preference for the “box of bricks for adults” over trailers and other factory-produced buildings. Gropius claimed that the panel system could “overcome the monotonization of form” that had made previous prefabrication schemes fail.

Nonetheless, examples such as the Packaged House Type A (the first one promoted by General Panel) still show some formal limitations. The maximum free span of any room in a structure made from 4X8 panels is 16 feet. With the modernist flourish of the v-shaped roof, the width is brought down to less than 14 feet per volume. In the factory-produced building, the volume would be determined either by the size of the factory assembly floor or by the width of the truck or highway-generally rectangular with a varying length of r6 to over 40 feet and a tightly controlled width of 8 to 12 feet, with the possibility of double· and triple-wide options if assembled on-site. The advantage of the panel system was supposed to avoid these strict tectonic limitations. Yet, without the use of a column support, which would break the purity of the panel system, the limitations remain.

The equation is actually fairly simple: the larger the module, or the fewer module types and techniques, the fewer the possible tectonic outcomes. So, in an extreme example, if an architect is interested in using only ship· ping containers as a module, the (very large) size of that module and its repetition will only yield a limited set of configurations: end to end, on top of each other, offset cantilever, and the trilithon, or “Stonehenge” configuration. The architect may instead choose a smaller module, such as a panel, with the hope of achieving greater formal variation and tectonic outcomes, but even a modestly sized module will impose tectonic limits based on its size, shape, and assembly. The Gropius example is instructive: the amount of free span and the rectangular shape of the panels would tend to yield 8-foot boxes. Of course, the module could become very small, or the assemblage varied, or one could introduce multiple systems, which would allow for wide formal variation, but doing so contradicts the point of prefabrication in the first place-that is, (inexpensive) expediency and ease of on-site assembly.

Even with advancing technology, limitations are part of the prefabrication game. There are certainly more and more examples of challenging panels on the market these days, with interesting surface forms and textures, but even these should remind architects of the limits imposed by module connection. No matter how gorgeous an interior panel may be, it is only as flexible as its track allows. And, without introducing another construction system or system of enclosure and structure, the panels are still just panels. In the Gropius example, the otherwise brilliant wedge connector makes for a fairly “dumb” box: right-angled connections enforce a strict orthogonality under an 8-foot by 4-foot proportional system.

For Gropius, however, the proportional system and strict orthogonality were in line with modernist doctrine-a distinct advantage of the system. In fact, he saw prefabrication not as an architectural endpoint, as it is often advertised today when we speak of this architect’s prefab or that architect’s prefab, but as a logical system preceding design. To this end, the panel system was an effective tool for promoting modernist sensibilities. Gropius often used his prefabrication system as a required technique in his design studios at Harvard. It was perhaps because of the necessary tectonic outcomes of the system and its strong modernist stylization that the Graduate School of Design became a recognized center of modernist architectural education.

More importantly, though- and especially from today’s perspective-the use of prefabrication as a pedagogical tool also implied that Gropius intuited that even the most elegant system required the trained hand of the architect. Indeed, the more elegant the system, the more architecturally limited it will become, and hence, the more it will require control over constraints to deliver the greatest formal variation. Gropius encouraged other architects to design using his system-an article in Architectural Forum was devoted solely to the range of design possibilities offered by their hands, Richard Neutra among them. While s till quite modern, and therefore stylistically limited, these designs do show configurations beyond Packaged House Type A. In other words, prefabrication may not be infinite, but shines a clear light on the role of the architect in producing what, in the end, is “architecture.”

Walter Gropius remained a prefabrication enthusiast throughout his life, despite the fact that the Packaged House venture did not survive in the postwar housing boom. But, when speaking of it in 1953, Gropius was quick to remind us of the lesson learned, “What is called the ‘freedom of the artist’ does not imply the unlimited command of a wide variety of different techniques and media, but simply his ability to design freely within the pre-ordained limits.”

Author Dora Epstein Jones, PhD, is the program coordinator of Cultural Studies at SCI –Arc and collaborator with Jones, Partners: Architecture in Redondo Beach. She believes firmly in the strength of the architectural discipline.

Originally published 4th quarter 2007 in arcCA 07.4, “preFABiana.”