The following introduction to “Wood, Earth, and Fiber: California,” Chapter 7 of Peter Nabokov and Robert Easton’s Native American Architecture (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1989) is reprinted here by permission of the authors.

Dugout floors and earth banking were insulating techniques used by many Indian groups in California. Twenty years after Drake’s visit, the Dutch engraver Theodore de Bry illustrated this Miwok domicile. He depicted five adults and one child sitting on fiber mats, together with the grass pillows the Miwok called hawi. The building, or kotca, “place where real people live,” is framed with two interlocking forked poles into which poles lean from around a circular floor. The covering material resembles slabs of redwood bark rather than the grass or tule thatching tied with lupine-root cord that ethnographic accounts of later coastal Miwok groups describe. The engraver emphasized the banking of earth insulation—probably fill taken from the slightly excavated floor-that extends part way up the outside walls.

Despite California’s generally temperate climate, the Indians were forced to shelter themselves from chilling fogs along the coast and sweltering summer heat in the valleys to the incessant winter rains of the foothills and the heavy snows of the high Sierra Nevada. These variations in local climate and habitat are reflected in the wide diversity of Indian house types found throughout aboriginal California.

For at least ten thousand years, California became home to a swelling population of emigrant tribes that ventured down the coast or entered from the north and east through mountain passes. On the eve of Drake’s appearance the region held more than 300,000 people—perhaps thirteen percent of the entire continent’s native population. It was also a culturally diverse population—six of native North America’s seven major language groups were represented in California, divided into more than one hundred dialects.

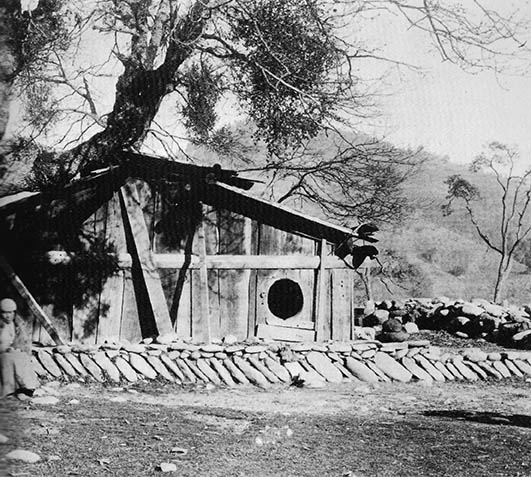

The Indian cultures of California have been subdivided by the region’s leading anthropologist, Alfred L. Kroeber, into four cultural “provinces,” each with representative forms of architecture. Located just below the present-day Oregon state line, tribes of the Northern province lived up and down the Klamath and Trinity River valleys and fished for salmon, hunted deer in the Siskiyou Mountains, dug clams along the Pacific tide line, and gathered plants. Here groups like the Yurok and Hupa built semisubterranean plank houses of redwood or cedar. To the southeast, on the eastern flank of the southern Cascade Range, were tribes like the Modoc and Achumawi, who constructed earth-roofed, semisubterranean dwellings.

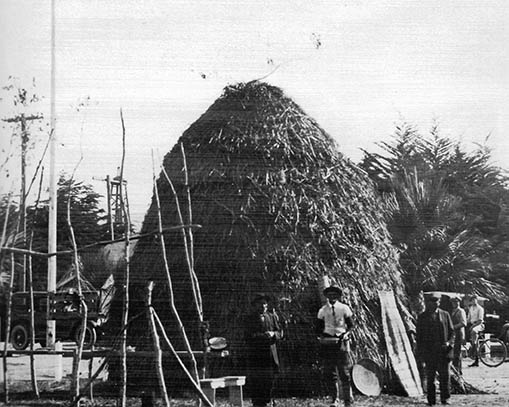

In the Central area, between the Pacific Ocean and eastward to the Great Basin, lived what Kroeber called “tribelets”—small autonomous groups of Miwok, Maidu, and Pomo speakers. Near the sea, their houses were made of brush or redwood bark. In the valleys, they usually built small pit houses. In the foothills they used more carefully constructed conical frames with redwood bark covering.

In the Southern province, bounded on the north by the Chumash tribal territories near Santa Barbara and to the south by today’s Mexico-United States border, simple dome-shaped brush structures were built before the Spanish arrived. Cooking windbreaks, large ceremonial arbors, and mud-plastered sweat baths often were found in their camps. After contact with the Spanish, however, form-molded adobe bricks became prevalent, which were mud-mortared into one-room thatched homes that resembled the Mexican peasant house known as a jacal.

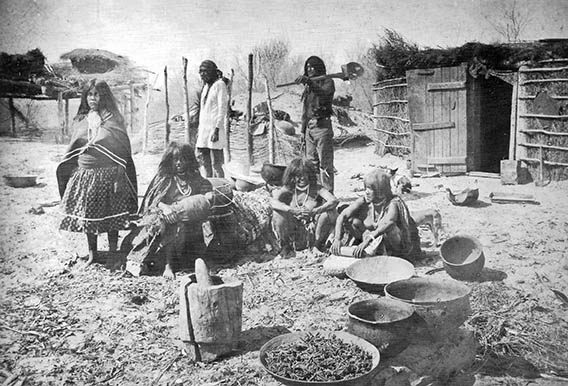

The fourth province stretched along the lower Colorado River basin, and in many respects seemed a world apart. The ways of its people—the Mohave, Quechan, Cocopa, and others—resembled Arizona Indian cultures as much as they did Southern California Indians. This collection of linguistically related tribes grew corn, squash, and beans in the silt-rich Colorado basin in the spring. But they also were fishermen, bird hunters, and proficient gatherers of nutritious mesquite and screw beans. In traditional times these tribes built four-post, sand-roofed houses. Like the smaller groups of the Southern province, however, they eventually adopted the Mexican jacal but walled them with arrowweed-and-daub rather than adobe brick.

Scholars categorize the rich array of California Indians on the basis of their language families and dialect groups. However, the linguistic approach fails to reflect the tribelet’s sense of identity, which was determined more by geographic, family, and local group affiliations. For most California Indians, “home” was the local hamlet and surroundings of one’s tribelet; it was the “central place,” in current archeological terminology, from which one ventured out in quest of seasonal foods.

Part of this collective identity was also the tribelet’s house type. In California, structures included a variety of summer and winter house types, open-air assembly arenas, earth-roofed dance chambers, sweat baths or “sudatories,” menstrual retreats, and a host of spaces reserved for processing and storing food.

California Indians regarded their environment as not only animate but ready to intercede in human affairs, an attitude that probably grew out of an intense awareness of their immediate surroundings. “The boundaries of all tribes,” the amateur ethnographer Stephen Powers wrote in 1877, “are marked with the greatest precision, being defined by certain creeks, canons, bowlders, conspicuous trees, springs, etc., each of which objects has its own individual name … If an Indian knows but little of this great world, he knows his own small fighting ground intimately better than any topographical engineer.”

Peter Nabokov joined the UCLA Department of World Arts and Cultures/Dance faculty in 1996. An anthropologist and writer, Nabokov has conducted ethnographic and ethnohistorical research with Native American communities throughout North America. His research and teaching explore the vernacular architecture of South India as well as his American Indian studies in the Plains, California, and the Southwest.

Robert Easton, AIA, is a fourth generation Californian who has designed and co-authored award-winning books on architecture, including Native American Architecture, designed many houses and commercial buildings, and recently done historical renovation of landmark buildings in Santa Barbara.

From arcCA DIGEST Season 08, “Indigeneity.”