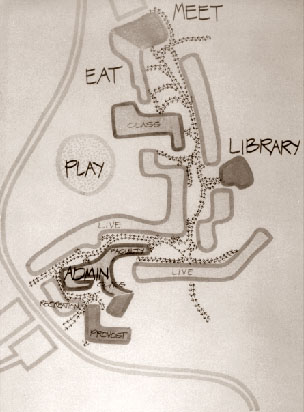

Kresge College is one of ten residential colleges located on the University of California Santa Cruz campus on a heavily wooded knoll overlooking Monterey Bay. Two sides of the site are precipitous, while the other slopes gently to the south. The program called for a residential college to accommodate 325 resident students and an equal number of off-campus commuters. Program requirements included student rooms, a library, classrooms, and faculty offices, as well as dining, recreation, and common areas. Students and faculty requested a “non-institutional” alternative to typical university classrooms and residences, which could be built within a very tight budget.

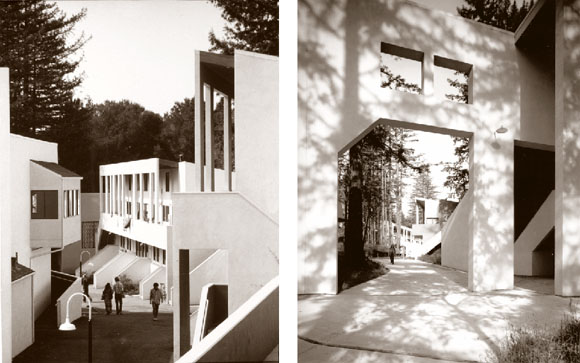

William Turnbull and Charles Moore’s answer to these challenging requirements resulted in small, two-story buildings grouped along a pedestrian pathway sited to respect the trees and terrain. “The street,” wrote Turnbull, “creates a center for the College, a place where people meet. It establishes a unique character and identity, . . . a space which organizes and enriches the life of the college in much the same manner that a street does for a village or small town.”

In Charles Moore: Buildings and Projects, 1949-1986, Eugene J. Johnson cites Kresge as an example of “large-scale planning that seems deliberately to eschew geometric complexities for an apparently relaxed relationship between building and environment. The basic idea of the street that meanders uphill in an irregular path came from a study of streets in Italian hill towns and Greek island villages. These kinds of urban systems, built over centuries by human beings in touch with their landscapes, represented . . . the kinds of environments that people actually wanted to live in.”

The residential accommodations offered students choices about how to live. Instead of the typical double-loaded corridor, the plan called for four-person apartments, each with a living room, two bedrooms, bath, and kitchen. More adventuresome students were given a “do-it-yourself” situation in eight-person groups. Walls, roofs, and basic plumbing and cooking facilities were provided, but the students built intermediate floors and walls of their own design. All rooms were furnished with a modular cube system that allows for unlimited arrangements.

The structures that house special functions are strategically placed markers along the street. The octagonal court at the upper end provides an entry to the town hall space and restaurant. The library is denoted by a two-story gateway. Other public facilities, such as telephone booths, are enlarged to become street markers commenting on the importance of communications in student and faculty life. The college is designed as a mixture of the serious and the playful, a place where educational processes can occur in both traditional and non-traditional manners.

As Robert A. M. Stern describes Kresge in Johnson’s book, “The College turns an earth-colored wall to the exterior to blend its architecture with the surrounding forests and create an enclosure and a suggestion of remarkable secrets for those permitted to enter. Inside, an eclectic array of building forms is disposed to create as richly articulated a stage set for human action as any ever offered by Hollywood. Kresge is a self-contained village within a larger university . . . . Moore aggrandized the laundry and canteen . . . to provide moments of architectural grandeur. An amphitheater, a red-white-and-blue rostrum, two-story dormitories that vaguely resemble roadside motels, administrative offices, shops, and a mailroom—all decorated with strips of neon—and freestanding walls with rectangular openings that visually frame the sky complete the assembly. The buildings are arranged along a grand, thousand-foot-long street—the thoroughfare of the College, intended to serve as its symbolic and functional nexus, the sort of linear quadrangle guaranteed liveliness by the movement of students along it.”

Thirty years later, Kresge is still both a fully inhabited college complex at UCSC and an enduring example of how to site buildings to respect their landscapes and enhance the lives of the inhabitants. “Kresge reminds us,” wrote William Hubbard in Complicity and Conviction, “that student life . . . comprised more than just the room, the library, and the dining hall. Kresge finds ways to use architectural form to acknowledge, even celebrate, those grittier aspects of life like washing, contacts with the outside, transactions with the bureaucracy . . . . When we see how Kresge’s space is articulated with seating areas and gathering places, how the surrounding trees are brought in at certain places, how the spine follows the natural contour of the ground—when we see all this, we realize that this space could be a space only for college students and that it could be located only in a central California forest . . . . Kresge . . . tells us that it could only have happened where it did, could only be meant for us.”

Author Mary Griffin, AIA, is a principal of Turnbull Griffin Haesloop. She served on the AIACC Awards Committee in 2002 and 2003 and will serve as its chair in 2004.

Originally published 3rd quarter 2003, in arcCA 03.3, “Done Good.”