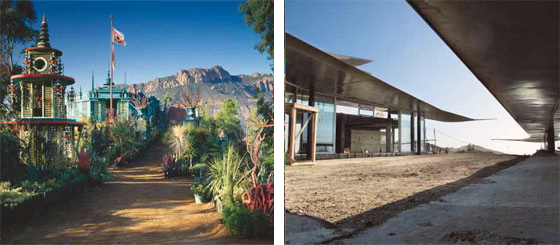

High in the Malibu hills, Tony Duquette’s former Sortilegium Ranch is getting a second life with the arrival of a Boeing 747, reconceived and reassembled as a house. Duquette—“Hollywood’s wild child of design,” in biographer Wendy Goodman’s words—was master of the decorative arts, from furniture to jewelry, costume to architectural design. His legerdemain with recycling was groundbreaking and unparalleled; egg cartons, antlers, and metal pipe all found new existences superior to anything they had known before. His work is an object lesson in reuse: long before architects were keen on green, interior designers and decorators were already hard at work repurposing and re-contextualizing objects. Most of the twenty-one structures of Sortilegium were destroyed by the 1993 Green Meadow Fire, leaving only a few small pavilions. Had it remained intact, the ranch would have be been one of America’s most singular and visionary design compounds.

Wing House is the work of David Hertz, FAIA, who, beginning in 1984, pioneered the use of recycled elements as an admixture in his “Syndcrete” concrete. Client Francie Rehwald, owner of a Mercedes dealership, requested feminine forms for the project; Hertz, well schooled in dramatic, organic form as an alumnus of the John Lautner office, offered the swelling curves of the 747. In the noble California tradition of William Wurster’s Gregory Farmhouse and Frank Gehry’s Whitney House, Wing House is a courtyard compound, each building fashioned from a section of the former aircraft. The lower half of the fuselage will be the Animal Barn, while the upended nose cone forms a forty-five foot tall Meditation Pavilion. Although it will indeed be a building, Wing House will retain enough of its former identity to require FAA registration, so that no one reports it as a downed plane.

A single family house that required $100,000 in materials delivery costs, including Chinook helicopter time and the closing of five Southern California freeways, is not about maximum efficiency in recycling. Yet, while 747s have been recycled before as buildings, this is the first of such buildings that is as much a work of art, as rich and complex an artifact, as the original plane. It is a rare occasion when design lightning and visionary recycling strike twice at the same location; Tony Duquette, who used old satellite dishes to make a lyric pavilion of his water tank, would be pleased.

Originally published in arcCA 10.3, “Design Education.”