In his 2011 article in arcCA, “Architecture and Enterprise: Potential and Pitfalls,” Mark Miller outlined criteria for architects to become innovators and enhance innovation as a professional practice foundation. His recommendations hold true more than a decade later. For this season on Innovation, arcCA DIGEST asked Mark to revisit and expand upon the ideas raised in that article.

The economic conditions affecting architecture in 2011, when I wrote “Architecture and Enterprise,” are mirrored in current economic stresses, and the contextual conditions of the built environment, including sustainability and resiliency, utilization and flexibility, remain challenges. While architecture continues to have an opportunity to provide innovative leadership and substance, to do so in a relevant and useful manner will require greater focus and practice enhancement than characterize the past decade. So let’s consider the Good, the Bad and Ugly issues and opportunities of contemporary and near-future conditions.

The Good: There are new challenges, markets, and opportunities for architects and their firms to be vibrant inventors and innovation leaders. We already have a high degree of training and tools. There are processes in nature and in business precedent to help guide us towards useful innovation. And there is increased recognition among practitioners that more fundamental practice change is needed.

The Bad: The open field of the Good is created by the Bad: a combination of architecture’s continuing negative impact on the environment and the AEC industry’s limited response to fundamental changes in the cultural and business needs that drive the markets for much of architecture. A central impact of these changes is that advancing societies may need a lot fewer new buildings, and may not need many of the buildings that are already in place.

The Ugly: The Ugly is architecture’s weak position in the larger landscape of problem solving, let alone as a resource for useful innovation. Judging from patent activity, new-idea market traction, and a web search for “architecture innovation scholarly articles” (more on this later) true innovation for the built environment has been incremental at best. The broader cultural and business domains that source architecture’s professional services and products have continued to marginalize architects and architecture in favor of other solution sets.

To get to architecture’s potential for innovation, let’s start with the three most significant conditions driving the impetus of need.

Environmental: Traditional building methods and results often remain ill suited to solving much of the built environment’s needs. Buildings continue to consume far too many resources to create and operate, take too long to build, and cost too much compared to viable alternatives. While recent buildings operate—and are occasionally sourced—more sustainably than in the past, these mitigations are a small fraction of their environmental footprint.

Cultural: Architecture must find more effective means to respond to the cultural dynamics of individual needs. One of architecture’s finest traditional values is its ability to reflect and support cultural conditions and narratives. In a slow-paced world, buildings that take years (or more) to create and decades to justify have been effective representations of collective cultural aspirations. But as societies advance economically, cultural experiences are increasingly defined from the perspective of the individual rather than the group. Culture shifts more rapidly and is harder to define at a collective level.

Technological: Virtual realities, digital meetings, and social media create useful and desirable alternatives for the cultural, professional, and commercial experiences that traditionally occur in physical space. They offer much more efficient and personalized means of interaction. Technological advancement has had similar impacts before. The telegraph, telephone, and television all made communications more efficient. Successful efficiencies gained through technology such as the elevator have opened new architectural territories. What is different now is that large organizations no longer demand physical proximity to collaborate. Engaging with physical places, at all, is a choice.

Consequently, as we see in vacant commercial downtown spaces from San Francisco, to Chicago, to D.C. and Atlanta, advanced economies and societies have little demand for (net) new construction. These US cities are projected to remain in this unviable condition for a long time. Even the commercial-development fever that captured Austin, Dallas, and Phoenix may be in jeopardy. Planners, investors and city dwellers probably wish there was a lot less architecture than is there today.

None of these three conditions is likely to reverse for a while, if ever. So, if architecture is to be innovative, it needs to start with accepting these conditions as the baseline rather than as accessory trends.

Addressing the Opportunities

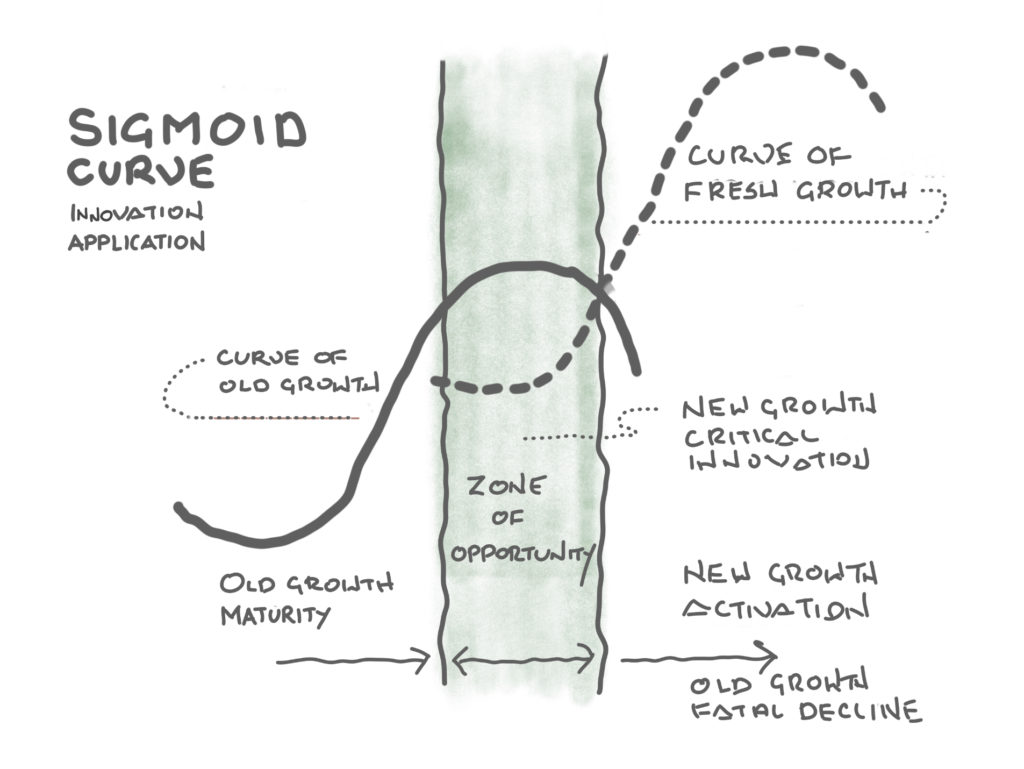

The path for innovators starts with an acceptance of such current and pending changes. It sets out to discover how to harness them usefully. This takes commitment to a new focus. A professional refocusing is intimidating, but it is also natural. An approach to it comes from a natural evolutionary pattern, which is also reflected in business, called the Sigmoid Curve.

The cycle follows an “S” curve defined by an initial parabola of organic growth and optimization. The apex of the curve inevitably turns downward towards decline. There is then a transition period during which new life may be created that can learn from and build upon the existing success of the prior entity before its ultimate decline. This period is the Zone of Opportunity, during which innovation is most relevant and effective. Missing the opportunity phase means decline and death, and extinction results.

The building industry as critical problem solver may be in this transition phase. Judging by the inability of our commercial and institutional buildings to offer, or appear to offer, a healthy environment for collaboration during the pandemic, and—perhaps more indicative—to bounce back after the worst of the pandemic, while business activity has remained at a stable level, it’s a viable thesis that much of the industry is well into the decline portion of the curve. Architecture and effective innovation are not currently aligned.

This misalignment is represented by the Ugly. Need proof? A tangible example of The Ugly is revealed simply through the Google search referred to above. Search “architecture innovation scholarly articles,” and you’ll find that (building) architects (as opposed to “software architects”) are not represented at all. No scholastically meritorious article on (building) architecture innovation is of enough popular interest to appear in a search that bears its name. Is that because we do not participate in significant scholastic research? Or does architecture participate, but the results are just not popular, significant, or relevant? Whichever it is, meaningful “innovation” (as defined by popular “scholarship”) is occurring in the design and construction of products, business practices, and computer science. Not in architecture for buildings.

When I eliminated the qualification of “scholarly” from the search, 20% of the items related to the AEC field. These results were mostly productivity tools for BIM and GIS. Sustainability design and travel site click-bait provide the balance.

I applaud sustainability appearing in this search. It is a critical practice for all fields, especially architecture. In practice, though, sustainability is not necessarily innovation. It is more often a creative application of prior innovation, and a slow one at that. Consider for example the “green roof.” This technique is found in the middle ages if not well before. Modern usage tracks to Scandinavia in the 1960s. (insert reference here)

As for those productivity tools, they do feature considerable software and hardware innovation that help make the practice of architecture more efficient. They surely also open means to make creativity—and at times innovation—more accessible. But, the application of these tools by architects tends towards the practice efficiencies that refine the means to continue practice as-is, with results that may seem fresher, but still follow the More-is-More model that drives the bulk of conventional architecture.

To claw our way towards the Good, let’s start with language: From Websters:

INNOVATION: noun

-

- a new idea, method, or product: NOVELTY

- the introduction of something new

That’s a relatively low bar, and it’s too easy. Novelty does not guarantee much in the way of substance. While there may be nothing wrong with novelty and the creation of the “new” for the sake of “new,” the best of architecture is more than that. Architecture, transcending the basic need of shelter, is most successful when it supports and reflects cultural aspirations.

Re-strengthening the position of the built environment as the host and representative of cultural aspirations could be the goal for innovation in architecture. If it were, then a new method or product should create a new result that either is fresh in its expression of cultural advancement, or enables others to advance cultural goals.

This cultural resonance comes from more than newness, than novelty. It comes from the ability of the innovation to stick in the marketplace of ideas and/or commerce so that it can have meaningful impact in solving recurring, culturally aspirational challenges. This impact over time becomes a measure of its value. In our contemporary and near-future world, the problem set for architecture should respond to cultural challenges that are most acute, which certainly include the environmental, cultural and technical ones noted above.

If my assessment is correct, and the architecture profession is subject to the Sigmoid Curve, then the profession and its innovators have a significant, if perhaps short, opportunity phase to invent the future through useful, meaningful, measurably successful innovation of a new industry curve. To invent along this new curve, innovators should consider replacing much of the investment in declining models in favor of focusing creative energy on the potential for new built environment methods, tools, and product solutions.

A flood of built environment architecture innovations leading an Internet search of scholarly articles and architecture practices would be a good sign of progression along a new curve. Reformation of architecture practices with raw invention, as well as innovative creative and strategic practices at the heart of their work would be an exciting second measure of rebirth and potential growth through increased usefulness.

The opportunities may come for the creative application of research and ideas to better form and operate the built environment in ways that reflect environmental, cultural, and technical change even—or especially—if it means less net building.

Consider the adage, “To a hammer, everything looks like a nail.” Instead of thinking and practicing like the hammer, if architects begin to find alternatives to pounding the world like a nail, the entire concept of problem-solving for the built environment might become way more innovative, way more quickly. If the perspective is shifted, so is the imperative to change.

Other fields realize this. Architecture innovators could benefit from engaging more collaboratively as peers with other fields that are more experienced with innovation and business model changes. Architects could learn much from future-oriented product designers, software engineers, and business managers. Also engaging directly, without a pre-agenda, with cultural and community leaders, constituents, and organizations would provide insight into the relevant priorities that architects could support.

Through this engagement, designers, sustainability specialists, technical and cultural savants, creative thinkers, and financial managers would be able to collaborate to solve problems at the forefront of culture and provide more effective use of architecture with considerable less consumption of the time, resources, and investment at the heart of the ugly and the bad.

Innovation could lead practice to increased value through alternative solutions such as improving the connections between virtual and augmented realities and conventional architecture, to avoid the growth of more low-utilized physical spaces.

Applying innovation to efficiency through digital solutions may also improve the physical spaces that remain. These physical spaces and the associated experiences they support may become more experientially rich. If basic needs are taken care of digitally, the use of physical space is by choice.

This practice would be meaningful, important, and justify the investments required. It would be on a new curve for future success. Though we may be building less, through innovation we would be solving more.

Mark R Miller, FAIA, is an architect and inventor who in addition to forming and leading MKThink, RoundhouseONE, and the newly established Ocean Plant, is the lead inventor for 18 patents in architectural systems, information visualization, and spatial intelligence. He is an occasional contributor to arcCA, including the 2011 piece “Architecture and Enterprise: Potential and Pitfalls” and through the periodic “Mark My Words” column.