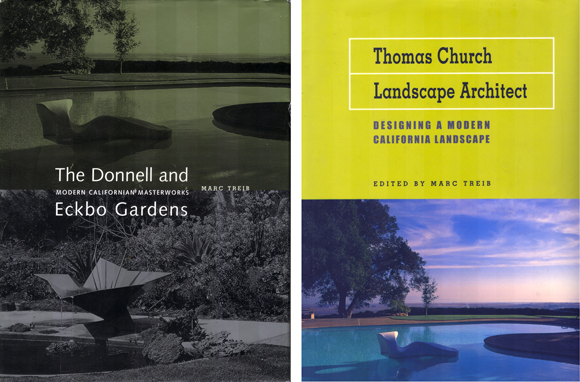

The Donnell and Eckbo Gardens, by Marc Treib, San Francisco: William Stout Publishers, 2005.

Thomas Church, Landscape Architect, edited by Marc Treib, San Francisco: William Stout Publishers, 2004.

Gardens have a long tradition as images of paradise: they represent a perfect world in miniature. The Donnell and Eckbo Gardens and Thomas Church, Landscape Architect examine the transposition of that idea to a place that, for many, already seemed like Nirvana: California in the middle of the twentieth century. The state’s mythic status was in large part the product of its landscape. Its physical beauty and mild climate were unique in the United States, and its abundant natural resources supported an intense version of the American dream of boundless prosperity. Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay Area experienced enormous population growth in the years during and after the Second World War, and the development of single-family housing on a vast scale posed a new question about paradise: How could it be found in the backyard of a middle-class suburban house?

The school of garden design that emerged in post-war California has not been thoroughly explored by historians, and The Donnell and Eckbo Gardens and Thomas Church, Landscape Architect take important steps toward describing and explaining some of the most significant projects of the period. Both books make use of primary-source photographs, drawings, and publications from the University of California’s archives. These images are accompanied by historical essays and, in many cases, by extensive and beautiful photographs of the gardens today. The Donnell and Eckbo Gardens examines the two most iconic designs of the era, Thomas Church’s Donnell garden and Garrett Eckbo’s Alcoa Forecast garden. Thomas Church, Landscape Architect places the Donnell garden in the context of the designer’s long and varied career.

Neither the Alcoa Forecast garden nor the Donnell garden was a typical middle-class undertaking. Each project was designed by one of the most prominent landscape architects in the nation. The Forecast Garden belonged to a series of showcase projects commissioned by Alcoa in an effort to develop new markets for aluminum. Eckbo designed and built the garden on the site of his Los Angeles house; his charge was to demonstrate how stock aluminum parts could be used to create an ideal outdoor environment. The Donnell garden was designed for a wealthy Sonoma County rancher, an heir to the Marathon Oil fortune. Yet, even though the circumstances of their creation were exceptional, both gardens provided powerful sources of imagery for Everyman. The Donnell Garden was featured on the cover of House Beautiful, and the Forecast Garden was documented in a short film broadcast during a weekly ABC television program sponsored by Alcoa. The projects also influenced other designers: each was widely documented in professional and trade journals and in books about garden design.

The Donnell and Eckbo Gardens is structured as two separate essays; each piece presents thorough documentation about the design, construction, and inhabitation of one of the gardens. What’s striking (and what the book doesn’t address directly) are the differences in sensibility between the two projects: they embedded similar ideas about program—low maintenance, high use, and flexibility—in radically different visions of a modernist paradise. The Forecast garden, enclosed on a suburban lot, had an immediate relationship to the family house; Eckbo designed aluminum sunshades to ameliorate heat gain indoors and to create a shady loggia between the building and the garden. The garden’s image and character rested on its use of a new material, aluminum, to create distinct, figured spaces: Its rhetoric said that a garden could be the locus of contemporary technology. The Donnell garden was located in the countryside and physically separated from the house it served. The project’s primary strategy was the construction of a visual relationship between its immediate location and the distant landscape of San Pablo Bay: The garden was a distillation and representation of its geographical context.

The Donnell garden was Thomas Church’s most famous project, but it was not the only one to exert influence on a large audience. Church was a prolific and long-lived designer, and Thomas Church, Landscape Architect, a collection of essays by different authors, documents and analyzes the range of his efforts. Dorothée Imbert’s contribution describes Church’s early career and examines how his education, travels, and working alliances with Bay Area modernists shaped his sensibility. Marc Treib provides a comprehensive review of Church’s mature design work, which included a wide variety of private gardens and some institutional commissions, and Waverly Lowell and Kelcy Shepherd lay out the contents of Berkeley’s Church archives.

Two of the book’s essayists deal explicitly with Church’s influence on popular ideas about garden design. Daniel Gregory describes Church’s relationship to Sunset, which published his designs and his writing and commissioned him to design its headquarters. Diane Harris, who discusses Church’s writing for House Beautiful and his enormously popular manuals of garden design, Gardens are for People and Your Private World, takes the most provocative stand in the book. The only essayist to suggest that Church’s cheerful, relaxed presentation of his ideas about garden design should not be taken at face value, Harris argues that his nonchalant tone masks a subtext: Design is best left to professionals, and fools who wander in alone suffer the consequences.

Thomas Church, Landscape Architect is a valuable resource for future scholars: it provides the kind of comprehensive documentation that raises additional questions. Harris’s willingness to look behind Church’s pronouncements could be profitably extended in other directions. Church often said that his garden designs were driven by program and by the desire to make pleasant places for human use, but the emphatically formalist character of all of the gardens represented in the book make those comments seem disingenuous. Treib and his contributors mention the effortless rightness of Church’s compositions, but they don’t explain what criteria determine rightness. Several of the essays emphasize the difference between Church’s biomorphic and Euclidean design vocabularies, but a careful study of what structures the gardens would probably reveal that both kinds of shapes are mobilized in the service of similar strategies. The next step toward understanding Church as a designer might be analytical studies of the gardens that look for underlying relationships of scale, proportion, orientation, organization, and choreography.

It’s harder to be optimistic about life in California than it was when Thomas Church and Garrett Eckbo did their seminal work: the place is fraught with problems. Despite that, their projects are full of relevant lessons: that new technology means new opportunities for expression; that gardens can express deep ideas about the places we inhabit; and, most of all, that part of our job is to create public consciousness about the power of design to enrich everyday experience.

Reviewer Jane Wolff is an assistant professor at the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University. She studied documentary filmmaking and landscape architecture at Harvard.

Originally published 3rd quarter 2006 in arcCA 06.3, “Preserving Modernism.”