The recent Modernist revival has reached popular consciousness. Television ads regularly feature Modern homes as backdrops for companies pitching new cars, pain pills, and phone services. The mid-century style has even made inroads into commercial developer housing. Is this merely a marketing trend, playing on the nostalgia of late baby-boomers, or is there something more essential at work here? Developers have typically sought to make their product attractive by employing vernacular elements to foster associations with familiar notions of home. Vernacular elements may be purely appliqué, such as face brick and half-timber, or formal elements, such as porches and dormers. Mid-century design has a vernacular of its own, although given the relatively minimal vocabulary of Modernism, its identifiable elements tend to be formal rather than purely decorative; broad expanses of glass and deep overhanging eaves are the product of indoor-outdoor planning, essential responses to lifestyle and climate.

Popular shelter magazines have proselytized this theme, echoing the philosophy of mid-century Modernist designers who argued that style is not the issue: The design, they claimed, serves to support the functional activities of the occupants, and expression is the byproduct of rational problem solving.

Exemplary recent developments in such hotbeds of Modern revival as Palm Springs offer convincing evidence that these concepts are appreciated and, indeed, popularly embraced. That these concepts have been adopted in sizable developments—the July 2005 Architectural Record features two Palm Springs tracts of forty-eight units each and a forty-six-unit development in Phoenix—demonstrate that recent Modernist projects have broached not only the issues of style and form, but planning principles as well. The apparent commercial success of these projects suggests they may well become models for future housing developments at a time when population growth and land values are booming, particularly in the West. What’s more, the architects for these housing projects—Will Bruder in Phoenix and the L.A.-based DesignARC for the Palm Springs projects—subscribe to specific mid-century design models. This suggests not only that Modernist design sells, but, more importantly, that its fundamentals remain viable. As newer projects are commissioned for much needed, moderately-priced housing on diminishing and increasingly precious land stock, design precedents that suit the climate and lifestyle of the West are increasingly valuable resources for designers.

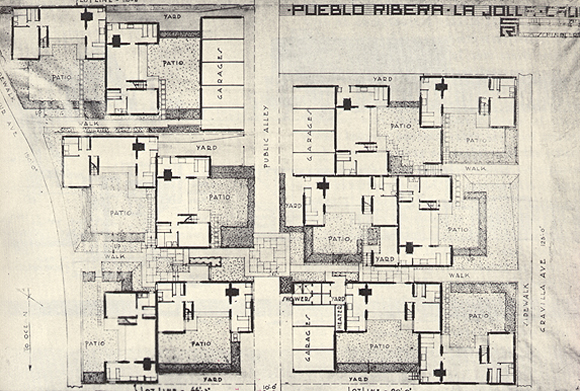

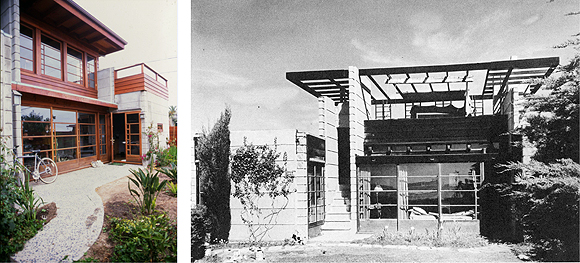

The models cited in the published examples above are from the familiar canon of California Modernists: Rudolph Schindler, co-founder, with Richard Neutra, of California’s European-inspired Modernist vernacular, and A. Quincy Jones, the long-time USC Dean, an inheritor of the style and long-time Eichler architect. The specific Palm Springs design precedents are not as predictable. The Schindler-inspired development, 48@Baristo, drew from the beautiful but somewhat obscure Pueblo Ribera project, a vacation complex in a state of decay since its construction in the mid-twenties near the coast in La Jolla.

Schindler, long considered second best to the more famous Neutra, has more recently received his due through a number of scholarly efforts, including the 1997 William Stout reprint of David Gebhard’s 1980 book, Schindler, which had been available for years only as a brittle paperback. Neutra and Schindler’s work was rooted in the fundamental tenets of European Modernism: economy of means, attention to health, and the ambitious use of modern building techniques. They brought a broad world view that encouraged others, including those who would design mass housing, such as the Eichler architects, to follow a design method marked by formal rigor but one that nonetheless reflected regional traditions.

The revival of mid-century Modernism is encouraging, because it acknowledges necessary economies and reflects regional values. A wholesale adaptation of mid-century technique is difficult; material choices are restricted by rising costs, construction technology is largely limited to conventional practice, and land values cramp the potential for indoor/ outdoor planning. Nonetheless, much of the best design work by the leaders of California Modernism was imbued with formal inventiveness and social purpose, and the products, both intentional and happenstance, have left us models worthy of renewed study when aiming for higher density developments that retain essential regional and modern characteristics.

Schindler’s Pueblo Ribera Courts, completed in 1923, although small (there are a dozen units), is a valuable example for reasons both practical and spiritual. At the scale of the site, the ingenious arrangement of C-shaped units, placed in connected pairs with party walls, ensured privacy for all the residents, despite their proximity. A single driveway bisects the layout, and two garages are tucked behind units on either side, concentrating the area for vehicular use. Access to individual units is by way of walking paths. These techniques, handled here with particular care and efficiency, are familiar and have been replicated elsewhere. What gives the complex its special magic is the degree to which Schindler has exploited the potential living spaces on each tiny lot. Each unit has three distinct types of living space: indoors, enclosed court, and roof terrace; each, as architectural historian Esther McCoy has pointed out, communicating naturally with the others. McCoy further notes that Schindler exercised strict economies of means in construction to support the most commodity from these minimum dwellings, creating light-filled living rooms opening onto private gardens and rooftop terraces with ocean views. The design fulfills Modernist ideals of inventiveness and economy while enriching the resident’s tangible experience of this archetypal Californian setting. Here, McCoy notes, Schindler has captured spaces that allow the owners to indulge in what he called “the vital luxuries of life.”

In the Bay Area, a number of community plans on various scales provide inspiration for reproduction. Joseph Eichler’s subdivisions are continually celebrated for their community values—planning strategies that anticipated PUD concepts. In the Berkeley hills, Greenwood Common is an accidental model of near ideal suburban form. Planned by William Wurster, the development consists of half a dozen homes by notable Modernists including Harwell Harris, Ernest Kump, and Schindler. The original plan called for a seventh home to fit between the others, creating a more or less solid cluster of private residences, unrelated to one another except for their common styles. However, the final piece was never filled in, and thankfully. It became a shared open space, a lawn with trees, big enough for picnics or games of touch football. A path leading from the green through a space between two of the houses allows a stunning Bay view. Even without this gorgeous setting, one can easily imagine the complex at twice the density as a reproducible module for new development, where a recurring theme is the profound desire for community. Greenwood Common suggests that interconnectedness, of social group and within a region, can be created by straightforward formal arrangements. With careful proportioning, the combination of closely spaced units and shared open space can foster familiarity and security.

Today, California is entering a period of extensive population growth. Planners anticipate an additional fifteen million residents in the next thirty years. Many of the new citizens will be middle class or working class, and affordable housing stock will be imperative. The revival of interest in Modernist housing seems fortuitous, if it also inspires renewed interest in the Modern Movement’s core values, which originated to address the housing needs of urban workers.

California Modernism flourished in the mid-century during a profound need for entry-level homes. The benign climate and lack of social tradition engendered a unique vernacular. Planning models, although often limited to small, one-off clusters, still provide meaningful expression and utility. America’s larger scale planning strategies from this period tended to prescribe forms derived from the automobile’s promise of an ever-stretching exurban expansion. Driven in equal parts by cold war fears and the implied moral purity of rural living, academics and leading practitioners alike envisioned a decentralized populace supported by small-scale industry and agriculture. Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City wove suburban and urban building typologies into a continuous fabric of regional agriculture and parklands. Ludwig Hilberseimer, Professor of Urban Planning at IIT postwar, imagined replacing the nation’s core cities with a regional pattern of small industrial parks and strips of cul-de-sac residential plats slung on either side of the snaking tendrils of a vast interconnected nationwide highway network, a vision that now seems remarkably prescient.

Recently, there has been a convergence of opinion among planners, developers, and academics that future growth can best be managed with more traditional urban forms. The key concept is connected space, which means neighborhoods with services and stores within walking distance of home. It also implies connectivity among social strata and age groups. Upwardly mobile families seek separate residences, while new immigrants, retirees, and singles need townhouses and apartments. Planners are responding to the diversity of housing needs with village precedents. Others are proposing reviving down-at-the-heels existing town centers and restoring transit routes ripped out during the car-centric 1950s. The scale of expected growth will require continued greenfield development, as well. Somewhere between New Urbanist ideals and Ludwig Hilberseimer’s new regional pattern lies a viable future course. California’s Modern legacy will almost certainly provide lessons for contemporary designers and planners. Additionally, I expect, we shall need to look back, as our predecessors did, to the sources of Modernism in Europe for typologies that can accommodate the emerging needs, high densities, diversity of residents, and multiple functions implied by our expanding culture.

Author Paul Adamson, AIA, is an architect with the San Francisco-based firm Hornberger + Worstell, Inc. He is the author of Eichler: Modernism Builds the American Dream and is a founding member of the Northern California working party of DOCOMOMO.

Originally published 3rd quarter 2006 in arcCA 06.3, “Preserving Modernism.”