The Berkeley campus is the oldest in the UC system. Established in 1868, its growth has been shaped by three distinct landscape design paradigms: Frederick Law Olmsted’s Picturesque conception of the 1860s; the Beaux-Arts formality of the 1914 plan by John Galen Howard; and the Modernist influence of Thomas Church and others of the mid-twentieth century, characterized by asymmetrical quadrangles and fluid pathways.

A series of planning studies, initiated in 2001 by then-Chancellor Robert Berdahl, has refocused attention on the form and role of the landscape.

The first of these studies, the New Century Plan, expanded the time horizon of the state-mandated long-range development plan, to investigate how UC Berkeley might prepare to respond to the population growth and changing demographics projected for the state over the upcoming decades. The New Century Plan lays out a strategic approach to capital investment, recognizing the importance of the landscape to the educational mission. In the words of the plan, “On our compact urban campus, where space is at a premium, each new capital investment must be designed to maximize its contribution to intellectual community by creating dynamic, interactive places.”

At the same time, an exhaustive seismic retrofit of the campus (the stadium is bisected by the Hayward Fault) garnered state and federal funding and prompted a massive renovation and building program. Together the New Century Plan and the seismic effort prompted a closer look at campus open space.

Campus landscape architect Jim Horner observed that no landscape master plan had been prepared for forty years and managed an in-house study by the University’s Capital Projects unit. The Landscape Master Plan, completed in 2004, cites four complementary elements that comprise the memorable landscape character of the campus: “the natural backdrop of the hills; the sinuous form of Strawberry Creek and its related tree canopy; the broad open lawns of the Central Glade; and the geometry of the neoclassical core.”

The Landscape Master Plan identifies specific areas for renewal and guides the future development in ways that can be attached to seismic projects or stand alone as the campus gradually transforms itself to meet new demands. One such example was the reconstruction of Sproul Plaza in 2004, funded by outgoing Chancellor Berdahl.

Before the master plan was completed, the Getty Grant Program awarded the campus one of its first Campus Heritage Grants to assess the evolution of the campus open space. The Landscape Heritage Plan, completed in 2005, identifies the three important eras of American landscape architecture represented in the campus—the Picturesque, Beaux-Arts, and Modernist—and articulates the symbiotic understanding of their interrelationship:

The landscape gains its power, rather than loses coherence, in the manner the layers meet each other and coexist. As in any symbiosis, something new is gained that no single layer alone could offer.

The question of the relationship among these three existing layers—and between them and future development—has been both deepened and complicated by the plan, which focuses on the Classical Core of the campus, where “[the] overlapping and intertwining of the picturesque, beaux-arts, and modern eras yield a rich and diverse dialogue of formal design languages.” Nevertheless, the name itself—“Classical Core”—reflects the predominance of Beaux Arts influence here.

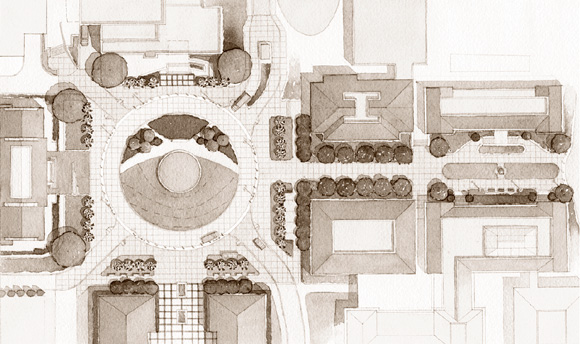

The two Implementation Concepts proposed as examples to inform future design further highlight iconic, Beaux Arts elements. The first of these, the Mining Circle / Oppenheimer Way, “resides within the campus’s [sic] neoclassical landscape type.” In the second, the Campanile Way / Sather Road site, while picturesque and modern elements are identified (Sather Road crossing Strawberry Creek and the plaza of Dwinelle Hall, respectively), the implementation proposal itself is confined to the strictly Beaux-Arts intersection of the two axes.

One member of the University’s Design Review Committee, Landscape Architecture faculty member Louise Mozingo, describes a planning process that for a time clearly favored the Beaux Arts period in its detailed guidelines, as well. As released, however, the plan’s Landscape Guidelines afford a range of possibilities for expression and provide examples of elements representing each of the three historical periods.

What the Landscape Heritage Plan does not do is articulate an attitude about the incorporation of contemporary or future landscape design paradigms. Its repeated calls for “maintaining,” “reinforcing,” and “enhancing” existing conditions may leave little room for other landscape layers, representative of the ongoing evolution of the field. Perhaps no plan can articulate formal guidelines for future conceptions— just as it is impossible today to compose a popular song for the year 2020. What remains to be seen, however, is how open UC Berkeley’s Landscape Heritage Plan is to the possibility of unforeseen enrichments.

Author Tim Culvahouse, FAIA, is editor of arcCA.

Originally published 4th quarter 2006 in arcCA 06.4, “The UCs.”