Jim Jennings (JJ) is an architect in San Francisco. A monograph on his work, Ten Projects: Ten Years is available from William Stout Books. You can view examples of his work at www.jimjenningsarchitecture. com.

Steven Oliver (SO) is President of Oliver and Company, a Bay Area construction company. He is chairman of the Board of Trustees of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

arcCA : How did you two meet?

SO: We were both at UC Berkeley at the same time and pledged a fraternity together, although neither of us ever became active members—in my case because I was on probation three-and-a-half of the four years I was in college.

JJ: Then it was twenty some-odd years later that we reconnected through our mutual association with the California College of the Arts (then called CCAC). I was teaching a design studio with the first group of students in the new architecture program, and I wanted to take them to see work under construction. I had heard that Steve, who was then chair of CCA’s board of trustees, had a ranch where he was starting a site-specific sculpture collection, so we arranged to stop by and take a look.

SO: But first you took them to Healdsburg to see the Jennings and Stout-designed house you had underway for Chara Schreyer.

JJ: Yes, and then we went over to Sonoma to visit the Oliver Ranch. We drove up the driveway expecting to arrive at Storm King; instead we found two laborers and a trailer. They were laying stonework for the main house.

arcCA : Who designed that house?

SO: I had hired Bob Overstreet, with whom I had worked before on some other projects. He was one of the five so-called “Goff Balls” in California—disciples of Bruce Goff who did very individualistic, beautiful design, but quirky. I had always wanted a stone house, so those two laborers Jim saw were at it for thirty-three months.

arcCA : How far along was it?

JJ: I don’t think the windows were in yet.

SO: Right. And to show you how well I had planned the project, the windows FOB on the truck were more than the original budget of the house.

arcCA : They were from Hope then?

SO: Of course.

arcCA : So Jim, how did you end up doing the interiors of that house, if Steve was that far into it?

JJ: While he took us on a tour of the house, he overheard the students talking about the Schreyer House. He asked if he could have the gate code to take a look on his way back to the city.

SO: I stopped by and walked through it. I realized that the calmness of its interior would be a perfect counterpoint to what Overstreet had done for my exterior, so I asked Jim if he would consider working with me. He said yes, and my wife Nancy and I have lived in various environments designed by Jim ever since. Jim even designed the extremely low budget CMU building that acts as our company headquarters.

arcCA : When was that ranch house project finished?

SO: 1989.

arcCA : What was the next thing you did together?

SO: The ranch house was relatively small, with only one guest bedroom and an open plan. I realized we’d need a guesthouse, so I asked Jim to look at a site near the main house that I thought could work.

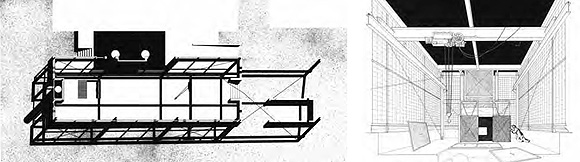

arcCA : This is the project that got a 1992 Progressive Architecture award?

JJ: Yes, although it went on hold for many years and was only recently completed.

arcCA : The idea had staying power, obviously, since it just won a 2006 Institute Honor Award for Architecture. Did anything major change from its original design?

SO: Only that I had the idea that we should incorporate an artist’s work into the construction. I had seen a temporary installation in New York at Barbara Flynn’s gallery on Crosby Street by an artist named David Rabinowitch. He had incised a plaster wall with these narrow cuts where the subtlety of the width and depth of the cuts were its brilliance.

arcCA : Had you thought about getting him involved initially?

SO: Yes, but he went through dealers faster than I could find a way to contact him. It was a blessing that we put the project on hold, because it allowed me the time I needed to finally get him involved.

arcCA : The way he went through dealers makes it sound like he was a bit of a large personality. As someone who works both with architects and artists, where would you rank the two on this subject?

SO: Architects are a distant second. So I asked Jim to go to New York to meet him and get it worked out.

arcCA : While the guesthouse was on hold, you two did a fair amount of other projects together.

SO: We worked together on some mausoleum work at Colma. We also did two projects with CCA ties: the Barclay Simpson Sculpture Studio on the Oakland Campus and a post-fire house in the Berkeley hills for CCA’s chair of graphic design, Leslie Becker.

arcCA : And for yourself, you built a nice house on Telegraph Hill.

SO: That one took seven years to build—longer than Mario Botta’s SF MoMA building, which I was leading tours of at the time as chair of their building committee.

JJ: Technically, that house was a remodel. We took down a four-unit apartment building and saved just one brick, building the new structure in the old building’s footprint.

arcCA : In that neighborhood, you still must have gone through hell with the neighbors.

JJ: It wasn’t too bad. When we held the obligatory neighborhood open house where you show the neighbors (and their lawyers) the model and plans so that they can prepare their opposition for the public hearing, there was some initial rumbling—“I don’t know about this . . .,” etc. Then in walks one of the most distinguished neighbors, Harry Hunt, a real connoisseur of architecture and design who lived across the street. He asked Steve, “Who’s your architect?” and when Steve responded, “Jim Jennings,” Harry said, “Oh, that will be fine.” All grumbling immediately ceased.

arcCA : The result was a Record House.

SO: Yes, but not before it was in Architectural Digest.

JJ: Record almost never names a project a Record House unless they have an exclusive on it.

arcCA : However, they made an exception and selected it the following year, to our knowledge the only time this has happened. Now by this time, Jim, you had worked with Steve as a client and his construction company as a builder for some time. Can you give us an example of the benefits of this familiarity?

JJ: When we were building the Telegraph Hill house, the superintendent, Steve Chambers, was forming up the base of the concrete cylinder that is the central element of the plan. He asked me whether I wanted an 1/8- or 1/4-inch reveal at the glass floor that would be at the top of the cylinder. This was for a detail that wouldn’t be realized for three years. That’s when you see the value of a well-developed client/ architect/builder relationship.

arcCA : So the client lived happily ever after in this wonderful house?

SO: I loved living in the house, but my wife Nancy hated the notoriety. One day I came home and she was showing six French architects around who had figured out where it was and just knocked on the door. She could never say “no” to anyone. There was also tremendous pressure from SF MoMA and others to use it for functions. The pressure of turning down these requests two or three times a week just wore on us. Meanwhile, I was building a TLMS-designed residential mid-rise near the Bay Bridge, which I took Nancy to the top of while it was under construction. While we were standing on the rebar on the top floor looking out at the bay she said, “Why don’t we sell that big-ass house and move here?” We bought half the top floor and had Jim design our new compact setting.

arcCA : Was it hard to find a buyer for the Telegraph Hill house?

SO: No. An attorney called me and said his client had read about the house and would pay me whatever I wanted. I arranged to meet them at the house and was told that the buyer was bringing his financial guru who said “no” to everything, so not to be upset when this unfolded. They pulled into the garage, I rotated their car around on the turntable we built into the floor of the garage and then took them up the red leather elevator to the open-air, glass-floored deck at the top. As we stood there overlooking the Golden Gate Bridge at dusk on what had to be one of only five warm days out of the year when you wouldn’t be blown out to sea, I heard the financial advisor whisper under his breath, “Pay him whatever he wants.”

JJ: Steve called me and said, “The bad news is we’re selling the house, the good news is we’d like to finally build the guest house at the ranch.”

arcCA : When Jim first started working with you, there was only one artist with work installed on the ranch—Judith Shea. How many are there now?

SO: Seventeen. The last of 600 concrete trucks was there last week finishing up the tower that Ann Hamilton created to serve as an interactive performance space.

arcCA : How has your work at the ranch with Jim and the artists affected your “day job” as the head of a construction company?

SO: It’s widened my awareness of the realm of possibilities.

Originally published 1st quarter 2007 in arcCA 07.1, “Patronage.”