From time to time, we continue a discussion begun in a previous issue, in this case arcCA 08.4, “Interiors + Architecture.”

The practice of interior architecture is an act of design that reinforces intimate relationships among individuals, communities, and the cultural artifacts that articulate meanings in and among these relationships. It is an investigation into the critical articulation of space and its social conditions. Elizabeth Grosz, in Architecture from the Outside (2001), writes, “The space of the in-between is the locus of social, cultural, and natural transformations . . . where becoming, openness to futurity, outstrips the conservational impetus to retain cohesion and unity.” In many ways, the idea she espouses echoes the importance of interior architecture, an importance whose main formal attribute is inherently about the in-between. It aspires to the design of space that is open to the possibilities of fluid interaction among multiple individuals and their relationships to the material world.

The notion of intimacy establishes a focused relationship between interior experience and the physical form of interior environments. Though all good design translates abstract ideas into physical form, intimate involvement with architecture provides a way of diminishing the abstract by embracing the specificity of meaning, feeling, and interaction that abstract ideas generate. The realm of interior architecture is filled with an intimate relationship between material artifacts and human behavior. The underlying desire of these relationships creates spaces where we house varied human interactions. It acknowledges that design requires a closeness that refuses to disassociate the human body and the varying states of human experience.

Affect

The connections between human behavior and spatial experience are better understood by investigating the notion of affect. In its common understanding in design, affect is often relegated to the list of secondary concerns. It generally refers to an interior mental state created by the manipulation of the senses and is closely aligned with affectation, which implies notions of trickery, pretext, and fiction.

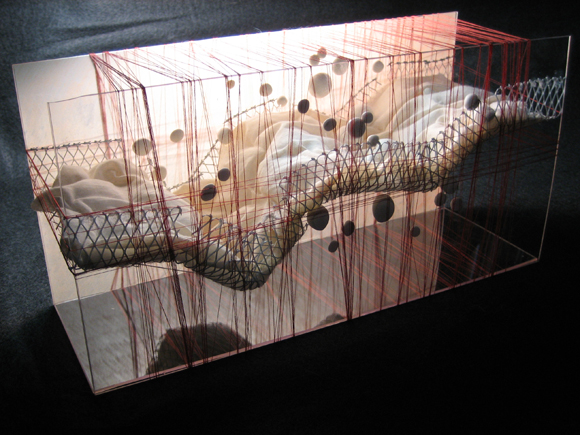

In fact, affect is better understood in its active meaning, as an ability to persuade. Though persuasion may enlist ideas of trickery, it is also an act of convincing. It opens the possibility that design becomes a communicative tool for breaking down preconceptions and establishing new ways of inhabiting space. As the complexity of human behavior and social dealings interacts with the designed environment, influence becomes a tool used to bring meaning to our interior environments. Material affect becomes a rhetorical wrapping of and exposure to sensuality in textures and colors that explore human conditions and translate them into the performative qualities.

Interior architecture becomes an emphatic questioning of the human condition, of social relations, and of our relationship with the material world. It questions how the building of form reinforces these relationships and interactions. The body of knowledge of interior architecture and its educational process enable participants to question the material world of interior space and the social relationships housed in these spaces—to question social norms and their spatial structures and transform them into notions of hidden desire and political action.

Hidden-ness and the Sensual

The technique of questioning and polemic found in the process of design also becomes an important underlying function of the interior environment itself. The function of inquiry of interior spaces relies on their in-between-ness and their hidden-ness. Jane Hirshfield’s essay, “Thoreau’s Hound: On Hiddenness,” eloquently articulates the human desire for knowledge by espousing the importance that concealment and the ungraspable play in the quest for knowledge. She writes, “Homo Sapiens: the name defines a species that wants to know. Yet an odd perversity equally present within us is thirsty for the opposite of knowledge . . . . A fidelity to the ungraspable lies at the very root of being. . . . Concealment does not presume conscious intention . . . . Hiddenness, then, is a sheltering enclosure—though one we stand sometimes outside of, at others within.” The interior realm then becomes a space for both hiding and revealing in our quest for the development of just and ethical design.

Seen from this perspective, interior architecture investigates a long tradition of architectural concern that emphasizes the hidden and ephemeral qualities of space. Volumes become transformed and transformative as new inhabitants occupy and appropriate the physicality of architectural form, structure, and the artifacts of the built environment.

As a social phenomenon, interior spaces are hidden within the textures of architectural form. The social performance within the hidden or intermittently revealed becomes a process that individuals and communities rely upon to uncover how we live, develop social strategies, and integrate these strategies into a larger public world.

The integration of the individual into the public realm relies on the familiarity with the sensual. It is dependent on many forms of sensuality, overtly and covertly. It starts with the body as the generative force behind the development of spatial form. It addresses those issues of design traditionally seen as transgressive to architecture: the sensual, the decorative, the colorful, the thematic. Employing material as a strategy for structuring space, it acts upon the senses and structures social relationships. Effect then becomes a tool of persuasion that reinvestigates the value of normative spatial and social structures.

The Inside In the Outside

Looking at a building from the outside reveals only minimally the possibilities of the lives and social structures that inhabit it. The inquisitive designer stands before an opaque object of inquiry. The profound effects of this form on the supposed lives wandering through the interior spaces are only occasionally revealed, and then often through fantastical desires built upon subjective story telling. When these lives are brought to the street, they are subdued by public appropriateness.

And so the design of interior space must rely on the intimate knowledge of those who will inhabit it. It relies on the transformation of general opacity into the specifically transparent, only to fade back to the opaque upon completion of the project. Paradoxically, then, interior architecture becomes less about closing off a hidden realm and more about opening up the possibilities of how interior space responds to the contextual and social conditions of a site and those who inhabit it.

Author Randall Stauffer is a professor and Chair of the Interior Architecture department at Woodbury University. He has practiced in the interior design profession for the past twenty years and is on the Executive Board for the Southern California Chapter of IIDA.

Originally published 1st quarter 2009, in arcCA 09.1, “Entitlements.”