History & Core Ideas

Jeff Logan: Derek, I want to reflect on the broader background of this practice. How does an approach to design move through three generations of practice?

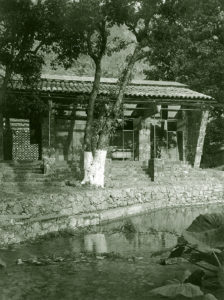

Derek Parker: I have to go back to the beginning. Bob Anshen and Steve Allen were trained at Penn, and they thought their curriculum was dated and artificial. Although they received “mentions” in the Beaux Arts method, they reacted against it. Their own inclination was that how you build should be the key design determinant, within the modernist context. They were focused on revealing the method of construction and solving the problem. You can see this clearly in the early small buildings. For example, at the Silverstone House in Mexico, they worked with what was available. The concrete beams were poured on the floor and lifted onto stone columns. They used materials that were locally available, like stone and wood—very little was brought in.

JL: What about some of the architectural influences?

DP: Frank Lloyd Wright was a strong influence in terms of relating to place and materials. I think Bob and Steve would say they were rationalists. They were not modern in the international modern sense. You see, the International Style, if we mean the strict European modernism, was like the Beaux Arts, in that it could be transplanted anywhere. Bob and Steve were more sensitive to the particulars of time and place. I would say that they were modernists in that they wanted to determine the most efficient way to solve the problem. Even if it was unsaid. There was a sophisticated sensibility in terms of how things are formed and the expressiveness of unique elements.

JL: Do you think the connection to landscape, the temperate California climate relaxed their modernism?

DP: Perhaps. Their being in California was an accident. When they graduated, they received travel scholarships and went to Europe and Asia. They settled in San Francisco because they had taken a freighter here from Japan. They needed jobs to pay their bar bill and get their luggage back. So the climate was just one of many influences. Serendipity played a part too.

JL: As it does in architecture. Looking at this early work, I would say they were focused on the tectonics of architecture as well as the poetics. They seem to have developed an architecture around place, site, materials, and technology. When they started, they were applying these attitudes to relatively small projects. But over the history of the practice those ideas have been expanded to larger projects that are more technologically complicat ed. How did this shift take place?

DP: In lots of ways, really. At its core is the approach I just mentioned, which is flexible. Over time, the people working here were interested in shifting from the small societal unit of the family to working with larger societal institutions.

Firm Growth/Protecting the Maverick

JL: But what was their process?

DP: Bob and Steve created an often contentious dialogue between two people. Steve was thoughtful, a beautiful draftsman. Bob was the talker, an idea a minute. They would fight; they scrapped a lot. It was a noisy drafting room. They would not accept a concept until both of them agreed. It all came from an argumentative discourse. That was their process. We’ve extended that dialogue, but structured it within a constructive design review process so everybody can participate. What that means internally is that no one person dominates. There are groups of teams. The culture of the office is that we all have a voice—we cannot predict where good ideas will come from.

JL: This isn’t a practice that foregrounds a single designer.

DP: No. In the beginning it was really Bob and Steve. When Bob died in 1964, Steve created a space for me to move into. The process became less argumentative, but Steve still encouraged debate. I did not replace Bob; the process changed. There has to be a lot of space, space for change, for new voices.

JL: I want to understand how the design principles evolved over time. How do you think the firm has maintained the core design values but encouraged change?

DP: There was not an epiphany or a great plan. I think it is a self-selecting kind of culture. Big egos don’t do well here, but mavericks do. In this culture we protect the maverick. As the firm grows, we are running a big business; certain things have to be done in a systematic way. But if you are not careful you squeeze out the mavericks and they are at the heart of the firm. They have to be nurtured. The mavericks are the ones who find the poetic spaces.

Connecting History to Today

JL: It is interesting that Bob Anshen was writing in the pages of Arts & Architecture in the 1940s about systematizing the construction of housing, and sixty years later we are still discussing it in the pages of Dwell. Other than nostalgia for the 1950s, what do you think is the lasting architectural legacy of the Eichlers?

DP: The Eichlers are a direct result of what we are talking about. They are part of the mainstream of the firm’s evolution. They are not a branch, but a result of the core principles. How could you build af fordable housing for GIs in this climate using the available technology? It is a societal question and a technological question. What should a modern house be like? They produced a simple, clean house that was in some ways mass produced, not factory-built, but a systematic building process on the sites. They were connected to the landscape; they were housing for California, not New England.

JL: Can you comment on the nature of the Eichler atrium? There is a precedent in the Spanish courtyards, but the Eichler atrium is smaller—in the scale of the composition, and often without any identifiable purpose, except as a landscaped space, a sort of quiet moment.

DP: We never talked about that, but I think you are right. A private space for the family and a place for them to entertain. I doubt it was in the program. We still use atria today as an organizational element in our academic and healthcare work. It is a place for meeting, it works much as it did in the house—the light filled center. Rarely is there a line item in the program for that kind of space.

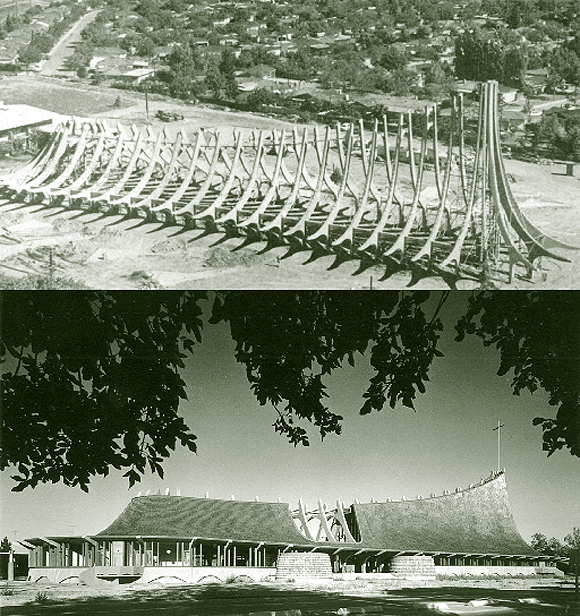

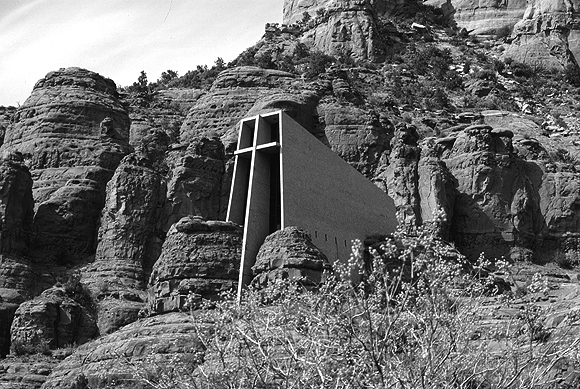

One of the partners from our Los Angeles office used to say that the most memorable places are in the gross and not in the net. They are rarely in the program; they evolve from how you connect the program. At the Central Methodist Church in Stockton those dramatic, but cost-effective, concrete bents provide the structure for the chapel, the community room, and the undefined congregating space in between. Sometimes, outside of an urban context, the poetic moment can be seen from afar. There is great clarity in the solution for the chapel at Sedona. Although distinct from the two buttes, it has an inevitability about it. I think this idea is one of the links between the early work, like the Eichlers, and the work we are doing today.

Contemporary Practice

JL: But the times are so different. How do you see these early principles extended?

DP: At your recent Diablo Valley College, you see an economy of means, every essential element becomes part of the architectural expression and that undefined space is in the generous circulation.

Yes, the times are more complicated. We are also more sophisticated in things like lighting and acoustics, mechanical systems, and the incorporation of technologies that did not exist when Bob and Steve were alive. Another aspect that has changed is the recognition that interior architecture is integral to a successful building. The interior and exterior are equal—it’s all one project. This is especially important in healthcare and academic research environments. The reality is that most of our users—students, patients, researchers, medical professionals—spend most of their time indoors, and they are profoundly effected by those spaces.

Part of the skill of the architect is to create some thing out of nothing—like a good chef. It’s in the amounts and the sequences. That hasn’t changed.

JL: Given the complexity of the large healthcare and education projects, a strong simple idea is central to the development of the architecture. But over time I think it becomes a war of attrition. For example, in healthcare architecture there are so many forces to contend with. If the idea is not clean and simple, it will be challenged and compromised.

DP: I can describe my favorite buildings in a sentence. The idea of the building should be clear and unambiguous. It is very important to have that idea. Then you can maintain that, protect it, and grow it, and don’t let people nibble away at it. You have to be able to answer the question: What is the big idea?

JL: I agree, but it happens at different scales. For example, at the Laguna Honda Hospital Replacement Project, all 1,200 residents will have their own window with a connection to the outside— that is a big idea at the scale of the individual. When designing the site plan, we had to deal with a number of existing buildings that will be in use until the new buildings are completed and occupied. But you don’t want a site plan shaped by the residual effect of soon-to-be demolished buildings— that’s the wrong big idea. In this case the site plan, when built out, maintains an existing strong idea—the residential units on the knolls. The linking buildings will house most of the community functions—they are a metaphorical and physical link—are placed in the valley. The pieces will read as distinct but interdependent. You need clarity at the macro scale, as well as the individual scale.

DP: At the individual scale, light is important for quality of life. At the end of a multi-year process, we are going to be able to say something simple. At Laguna Honda everybody has a window. This was under attack almost daily for two years. We stuck to the idea.

Looking Back/Conclusion

JL: Looking back at the practice, what would you have done differently?

DP: I would have emphasized our connections to the academic community earlier. You seem to be correcting that. My mentors were really Bob and Steve, but yours are more related to your academic experience.

JL: The kind of modernism that I was drawn to was not so much a stylistic one as a social one. That came from Berkeley, and I suppose from Harvard, from Maki and Moneo. Fragmented buildings or buildings that are formed largely by aesthetic forces outside the challenge of the project—that is not what interests me.

DP: We had no training in the social sciences. My thesis was a humongous block of apartments like Unité d’Habitation. The tenants would have been criminals in a month! The firm’s strength has been in projects that have some social context. You know John Dewey said something like, “Health is the first liberty.” If we can raise healthy kids we can educate them. Children are the intellectual capital of society. If adults are healthy, with their basic needs met, they can participate freely in a democratic society. The architect has a central role to play, especially in healthcare, education, research, and working conditions. Our clients are motivated because they are doing something important, something that contributes to the public good. We believe that architecture can help, whether we are healing people or educating them.

Derek Parker, FAIA, RIBA, Chairman of the Board of Anshen + Allen, joined the practice in 1960. Jeff Logan, AIA, Director of Design, joined the firm in 1995. Historically, the firm is well known for being one of the practices that designed Eichler homes and some important modernist churches. More recently, they have been recognized for their academic and healthcare work. We asked them to sit down and discuss the practice and how spaces of reflection found their way into the firm’s work over three generations.

Originally published 4th quarter 2003, in arcCA 03.4, “Reflect Renew.”