As the year began, construction cranes dotted the landscape in Downtown Los Angeles. By midyear, buses, light rail and heavy rail were running extended hours beyond midnight to serve the city center’s several entertainment venues as well as multiple shifts of employees. Despite the general perception, Downtown Los Angeles remains the chief generator of jobs, incomes and revenues for the region. Its crime rate is remarkably lower than that of many other parts of the city. Within Downtown are fascinating places and buildings and a large share of the region’s primary cultural institutions. Revitalization is needed in very specific locations where promising initiatives are already in process, but, overall, an evolving Downtown requires something more like filling in and filling out, repairing, tuning—indeed, a continuation of the processes of city building and place making.

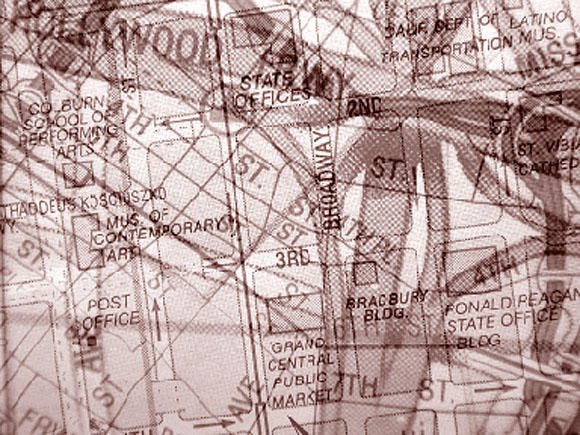

A strategic plan for Downtown was adopted in 1993 and is being implemented through numerous actions. It lays out how to interrelate Downtown’s three main zones, how to provide for continuity and change, how to weave a whole out of parts, how to take catalytic actions and how to establish physical frameworks. It argues the need for leadership in the private sector, which has occurred in the form of a number of Business Improvement Districts (BIDs) and a myriad of non-profit entities. The formation of these organizations has been as important in developing cohesive communities as in creating focused attention to immediate locations. Downtown is a cluster of interconnected special districts and neighborhoods. In the future, as now, Downtown will not be able to be summarized in sweeping terms. Instead, it must be understood more as a complex place of mix, of history and beginnings, of change, of the challenges and difficulties of mega-city urbanity.

The attraction of an urban center is its range of activities, resources and places. The array is more accessible in older cities with rather small blocks and dense building texture than in newer urban centers where wider streets have been sized more for passing cars than for crossing people. Moreover, older streets that were designed for a better balance of foot and vehicular traffic were furnished to create suitably comfortable environments. After decades of neglect, many cities have taken a new interest in such urbanity. The streets of Downtown Los Angeles await this attention: within and between the sub-districts there is little continuity of pedestrian accommodation, and the districts seem disconnected from each other.

Still, much has already been done. The Community Redevelopment Agency required all development during the 1970s and 1980s to include not only sidewalk improvements and uses but also impressive inter-district connections. Among the most conspicuous of these are the steps that join Bunker Hill with the urban terrace below at Bertram Goodhue’s landmark Central Library and the restoration of the Angel’s Flight funicular connecting another side of Bunker Hill to the historic core and to new rail transit. Hill Street has been transformed to better accommodate both buses and pedestrians. Broadway along its historic theater district is being repaved and will soon have new sidewalks and proper street furnishings. Figueroa Street improvements have been initiated and are ongoing. Markers have been put in place to identify landmarks and provide cultural information about them. In a very large Downtown these improvements to the public realm appear dispersed, but they are evidence of a will to establish a more supportive setting for urban life.

The Downtown Strategic Plan was centered on the understanding that only when a substantial resident population was present could the districts provide the services and amenities, necessities and enrichments that comprise urbanity. Just 4,000 people currently live in Downtown, but that will soon change, as a number of new housing projects are underway to satisfy the surprisingly high demand. Conversions to lofts on the east side are so popular that vacancies are filled from long waiting lists. Ira Yellin’s risk-taking conversion of office space to housing above the Grand Central Market and Million Dollar Theater has generated equally great demand. Now other such projects—several in the historic district are in construction and others are in planning stages—are following under the guidance of developer Tom Gilmore, who expects the Downtown residential population to grow to more than 30,000 in the next few years.

At the western edge of Downtown a less urbane, more enclosed housing project is well under construction. It is proving attractive to center- dwellers who continue to aspire to suburban interests. Two other housing projects recently won awards from the AIA/LA Chapter. The Villa Flores, designed by John Mutlow, FAIA, provides additional elderly housing in an area of earlier housing projects on their way to becoming an actual neighborhood— with a park, good services and high access and convenience. A new Downtown Drop-In Homeless Shelter by Michael Lehrer, AIA, (an AIA/CC Honor Award winner, to be featured in the upcoming Design Awards issue of arcCA) augments a spate of housing projects in support of the homeless and those working their way back to self-sufficiency.

The excitement in Downtown during the 1980s and 1990s was new office towers. The best of these, such as the Library Tower by Harry Cobb, FAIA, were not only handsome themselves but adventurous in connecting to their sites. They were programmed to include little retail space inside: their very large numbers of employees have been encouraged to use the restaurants and retail services of the adjacent district. Thus these buildings have been catalytic forces in ways distinct from their internally complete predecessors. Overall, however, office space was over- built, and as banks and other corporate entities merged and remerged, Downtown vacancies soared, with an impact on all other sectors. While that flight may now have reversed course, few observers expect Downtown to retake its position as a primary location for new office construction.

Instead, the excitement of the current moment, beyond the new housing, is the creation of extraordinary cultural destinations. By the mid-90s, Goodhue’s library had been deftly restored by Hardy Holzman Pfeifer as part of an extensive expansion; Lawrence Halprin’s adaptive restoration of the library’s original garden covers a large parking facility below. Nearby, Ricardo Legoretta, Hon. FAIA, and Laurie Olin, Hon. AIA, redesigned Pershing Square, which has periods of high use but is yet to be properly managed. (Still, it includes the range of open space choices needed at the core of the city: its winter carnival ice rink has been a great success, drawing people from vast distances; its summer concerts are important to Downtown workers and residents.) Up the hill, next to the Museum of Contemporary Art, by Arata Isozaki, Hon. FAIA, is Hardy Holzman Pfeifer’s new Colburn School of Music. A substantial conservatory with residential quarters is also planned for the area. Across from all of that, the Walt and Lillian Disney Hall, by Frank Gehry, FAIA, is finally under construction. Just a full block away, the Cathedral of Los Angeles, by Rafael Moneo, Hon. FAIA, is also in construction.

To the south, Staples Center has opened as the court of the Kings, Lakers and Clippers. Its 18,000-seat arena also provides a setting for major concerts. Parking for these venues is insufficient on site, and many have to park at a distance and walk through Downtown. Owners of the properties along these routes have noticed the action, and numerous development proposals fill the air.

Still further south, at University Park, are important additions. Exposition Park has been given an excellent new master plan whose first increments have been realized in a corner park, interior open space reworking, and the California Science Center designed by Zimmer Gunsul Frasca. Great attention has been given to improving the Coliseum, pending the moment that professional football returns to the region. In the meantime, it remains a site for major college football, for soccer and for convocations. The University of Southern California has been trans- forming its campus with a number of new buildings and extensive open-space improvements. USC is now proposing a 12,000-seat events center on Figueroa Street across from the main campus—another site for sports and cultural events.

All of this activity can be placed in a community-oriented framework. The longstanding role of Downtown in support of the downtrodden has continued with the new missions, parks, drop-in and other service centers. The BIDs are developing a business community once again in a position to provide necessary services, to create a habitable public realm and to generate new business activity and jobs. Housing projects are supporting the widest range of needs and interests from the bottom to the top of the economy. And unique destinations are establishing a social mix at the heart of this stretched-out city.

The prospects are encouraging for the future. A new council member for Downtown will soon be sworn in and will inevitably be more interested in the connections between development and community than the current officeholder has been. Disney Hall will become the city signature and encourage surrounding development as well as regional pride. A significant plan for the civic center called “The Ten Minute Diamond” is timely, as a number of new government projects are at advanced stages of planning. Those involved in the planning identify 28 projects going forward in or next to the civic center. Each has a community it serves, and, together, the widest range of communities will have centers of interest that support Downtown.

Throughout its history we have seen comparable periods of intensive development in Los Angeles. Thus we know that such rapid infusions of energy do not by themselves create wonderful urban places. But at this moment more positive expectations may be in order. Architects like Gehry and Moneo, HHP and ZGF, and Mutlow and Lehrer care about urban place and urbanity, not just about object-minded projects. If architects working in all of our Downtowns can rise to this level, we will not once again be left with the bard’s sound and fury of disconnected, self-serving projects. Instead, we will create truly evocative settings for our diverse communities.

Author Robert S. Harris, FAIA, is a professor and urban design consultant. He directs the University of Southern California graduate programs in architecture, was dean of the schools of architecture at USC and the University of Oregon, and has been named a distinguished professor by the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture. In Los Angeles, he has chaired the Mayor’s Urban Design Advisory Panel and the Downtown Strategic Plan Advisory Committee.

Originally published late 2000, in arcCA 00.2, “Common Ground.”