Walk north on Balboa Boulevard in the San Fernando Valley from the commercial hurly-burly of Ventura, and in 200 feet you’re deep in the suburban grid that consumed square miles of chicken ranches and orchards in the 1950s. Today’s landscape looks domesticated, but the light is for a desert, simplifying everything into glare or shadow. By 10 a.m. on this Sunday morning in August, half the slightly milky sky is incandescent and the valley heat is already a material presence. What you need is shelter. What’s available is mostly nostalgic, given that virtually everyone here was, less than sixty years ago, an immigrant, full of longing.

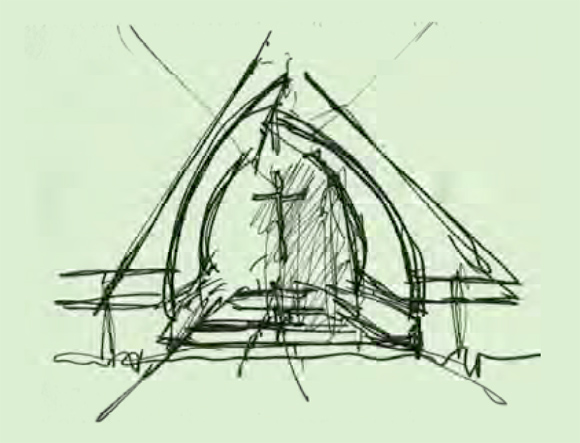

The campus of the First Presbyterian Church, a block up from Ventura Boulevard, replicates the immigrants’ longing and some of their provisional remedies. The original church from 1945 is a vaguely English, half-timbered shed constructed, one parishioner told me, with the help of the actor Edward Everett Horton. Attached to it is a more substantial block of classrooms and offices that implies an abbey cloister. The second church, put up in 1954, suggests its European roots with a shorthand of historical detail applied to the exterior of the simple A-frame structure. There are hundreds of churches like this in the city’s mid-century neighborhoods, evoking comfortable traditions on a framework of everyday modernism.

But it’s too bright to stand outside considering this utilitarian coupling. You want shade.

Step inside the newly remodeled church and what you get is more light. It’s light with a remarkable emotional range and almost always presented—even when it’s artificial—with great subtlety and sophistication. It’s never unmediated light. It’s light that’s passed through something, been cut by asymmetrical openings, allowed to screen on a tilted and curving panel, been half blocked by the overlapping edge of another, let to gather in irregular polygons from fourteen mostly unseen skylights, been reflected onto white oak pews and absorbed by the deep gray of the carpeting and the concrete chancel platform. It’s as if you had taken a platinum photographic print and enlarged it to wall size blocks of tones graduating from not exactly white to not quite black.

And this pervasive, ambivalent light isn’t static. The succession of cool tones modulates minute by minute as the morning sun climbs and follows the ridge of the roof, turning the recesses of the east facing chancel wall into a gallery of monochrome abstractions. A comparable experience—interior light as theology—is in the church paintings of the early 17th century Dutch artist Pieter Jansz Saenrendam. He caught the pale northern light pouring over Gothic pillars and arches from the clear windowpanes that had replaced the stained glass in the stripped and whitewashed naves of newly Calvinist cathedrals. Saenrendam painted the undeceiving light of reform.

The members of the First Presbyterian Church are still getting used to its appearance in their California neighborhood. When an usher, working the unfamiliar controls before the service, extinguishes the spotlights that define the altar in front of the chancel and the opalescent plaster of the 16-foot-high cross that projects into it, the remaining daylight is much less metaphoric. It’s more nuanced in shades of gray, more capable of affirming the physical qualities of the plaster-over-sheetrock of the large side panels, more architectural, and even more mysterious (and less liturgical) in the way it compels attention to its passage over the planes and angles of the chancel wall.

Whatever it might be as neutral space for manipulating light, this sanctuary is a machine for praying in a particular way. With the spotlights back on and the service begun, the worship space reorganizes around the hulk of the black grand piano accompanying the hymn tunes, the six-foot-high video projection screen displaying the order of today’s service, and Pastor Malcolm Laing standing at the ambo reading aloud the words of the Gospel. However diminished, there is a parallel text in the light animating the white panels that bend and clasp over his head.

This luminous church interior deservedly earned the AIACC Honor Award for Design in 2003. Apart from the astonishing beauty realized by principal architects Trevor Abramson and Douglas Teiger, with Michael Cranfill, architect in charge of design, the work took just seven months to complete and cost less than $900,000.

The optimistic lesson of the First Presbyterian Church is that a lyrical, humane modernism is a fit alternative to nostalgia in making sacred spaces in southern California. Hundreds of suburban churches from the 1950s, crowded with shadows, await the new enlightenment.

First Presbyterian Church, Encino, remodeled by Abramson Teiger Architects in 2003, with lighting consultant Bridget Williams, structural engineer Soly Yamini & Associates, and acoustical engineer Martin Newson & Associates. General contracting by AJ Engineering & Construction Company.

Author D. J. Waldie, public information officer for the City of Lakewood, California, is the author of two books: Holy Land: a Suburban Memoir and Real City: Downtown Los Angeles.

Originally published 4th quarter 2003, in arcCA 03.4, “Reflect Renew.”