For this issue dedicated to the City of Los Angeles, arcCA sought views of L.A.’s built environment from a diverse, super-baker’s-dozen of authorities. These are their thoughts, grouped under six arbitrary sub-headings: Getting Better, Getting Denser, Getting Around, Getting Down, Getting Out and Getting About.

What Kind of Paradise?

A native of Los Angeles, David Thurman is an Associate at Moule & Polyzoides Architects and Urbanists in Pasadena, where he was project leader on master plans for Occidental College, New College of Florida, and the Olympic and Soto mixed-use center in Los Angeles. Thurman has written for periodicals such as World Architecture, Center, and Texas Architect, as well as arcCA.

I grew up during a time of tremendous growth in L.A., the 1960s. I recall playing on home construction sites in the hills of South Pasadena and collecting the metal punch-outs from electrical boxes as if they were gold coins. At that time, it felt as though we lived in a quite rural place, happily climbing trees and roaming hidden corners of the undeveloped landscape. This was an abundant natural environment full of giant eucalyptus trees and rolling hills. For most of the time until the 1960s, this could have described many parts of southern California; the idea that it would soon dramatically change was far from anyone’s mind.

The transition from this child’s paradise to a denser and grittier Los Angeles has been a difficult one, probably because no one wanted to admit it was our destiny; no one wants to change one’s own version of paradise. Yet by the time I graduated from high school in 1976, there were signs of extreme crisis. We had over 150 first stage smog alerts in the year that I took up distance running with the school track team. Despite such horrors, the 1976 attempt to integrate the first HOV lane in Los Angeles was a famous political disaster, resulting in the installation (and hasty removal) of “diamond lanes” on the Santa Monica Freeway. Other hopes for transportation relief, such as regional rail transit proposals, had failed in both 1968 and 1974. By the time I graduated from college in 1980, things had further deteriorated, and we had over 200 first stage alerts. It obviously was difficult for people to make concessions to the freedom offered by the automobile and the desire to retreat to the private realm; it would require much more time for public opinion to adjust to the idea of Los Angeles as an urban place. It has taken some rather hopeless years in which Angelenos have suffered the pressures of growth. We have had to weather freeway shootings, riots, excessive pollution, and two-hour commutes in order to realize that there must be a better way to live.

Finally, we have responded. Population growth, pollution, and the cost of housing have encouraged us to build greater density, to seek transit alternatives, and to revitalize our aging downtown. The results are encouraging. By 2002, we had gone though two consecutive summers without a single, first stage smog alert. Our ailing downtown has experienced a renaissance, with nearly 20,000 residential units planned or under construction. Southern California now has a total of seventy-three miles of light rail and subway lines, nearly 700 miles of HOV lanes, and an express bus that inexpensively connects the airport to downtown. There are signs that people are finally aware that long commutes from low-density suburbs are not the only way to enjoy living in Los Angeles.

Although Los Angeles has a long way to go to become a truly integrated urban environment in terms of housing, social needs, transit, place-making, and sustainability, it is striking how far we have come. Thirty years ago, we knew there were problems but were reticent to embrace meaningful solutions. In contrast, today there is incredible optimism and an eagerness to try new approaches. Although my pleasant childhood memories are difficult to forget, it is now possible to imagine Los Angeles as a new and very different kind of paradise.

The Polymorphous Polyvalent Polis or Can Sprawl Spawn Splendor?

Buzz Yudell, FAIA, is a partner in Moore Ruble Yudell Architects & Planners, winner of the 2006 AIA National Firm Award.

L.A. is a sprawling metropolis metastasizing beyond control. L.A. is a fertile and flexible urban network supporting innovation and adaptation.

As in all clichés, there are truths in both statements. L.A. has its share of dysfunction, often observed with schadenfreude. It has its inequalities, its pretensions, and its noir secrets. But its other secret, particularly to those who know our city only in passing, is that L.A. is a rapidly evolving ecology, which supports innovation in the arts, science, and industry, and which accommodates a diversity of patterns of living and working.

The overlay of horizontal sprawl (of some 1600 square miles) on a landscape limited only by mountains to the north and the ocean to the west has allowed the development of a polymorphous urban network. L.A.’s very problems—sprawl, lack of focus, lack of density—are ironically becoming its strength.

The city seems to be at a point of inflection, where local densification is creating viable mixed-use communities within the larger network. Like a neural network, new pathways are formed where energy circulates, and the accumulation of these formations leads to a densification of activity and use. One urbanist has referred to Los Angeles as polynucleated. We are beginning to see that the lack of a single downtown has not inhibited the formation of lively neighborhoods and communities of varying scales, functioning in both complementary and independent fashion. From Pasadena to Chinatown, Los Feliz, Hollywood, Culver City, Mar Vista, Santa Monica, Inglewood, and beyond, densifying neighborhoods are creating greater opportunities for choice in living, working, and cultural life.

Twenty years ago, I wondered how young architects joining our office would be able to afford to live in Los Angeles. By then, they had been priced out of many parts of the city. Yet, in successive waves, they and others found new niches in evolving communities. When priced out of Santa Monica, they found refuge in Venice or Hollywood. When priced out of Venice or Hollywood, they moved on to Culver City or Los Feliz. Now, they might be finding reasonable housing near Mt. Washington, Chinatown, or Inglewood. With each of these waves, more neighborhoods become focal points for densification and cultural amenities.

In addition to the spatial diversity, there is a marvelous overlay of ecological diversity. We recently visited an architect-chef who had found her perfect nest in an affordable rental of a mid-century house, nestled in the hills of Silver Lake with spectacular views and connections to the land. Within sight of this house, we dined with an architect-writer north of Chinatown, whose urban setting allowed guests to drive into his converted factory loft, guided by candles like the lights on an airport runway, to arrive at a dinner set alfresco in this capacious factory. Both of these friends spend part of their time working from home.

The mutability and even the much derided disposability of a great deal of Los Angeles’s “provisional” architecture has allowed fragile and sometimes marginal initiatives to take hold, as well. For years, small entrepreneurs have been able to rent out bare-bones Quonset huts and lofts adjacent to the Santa Monica airport. The derelict lofts of Bergamot Station have become an economical setting for a vibrant art and design center.

Such renewal is happening not only in the more affluent Westside, but is sprinkled throughout the city in such places as central L.A., the site of the new L.A. Design Center by John Friedman Alice Kimm Architects, the “Brewery,” an artists collective north of down town, or the many conversions of early twentieth- century downtown office buildings into work-live lofts.

For years, L.A. has been a place of private opportunity and occasional splendor counterpointed by public apathy and occasional squalor. We’re all aware of the welcome increase in iconic architecture, from the Getty to Disney Hall to the new Cathedral and the Cal-Trans Headquarters. A less known and perhaps ultimately more powerful trend is occurring in the fabric of the city. Throughout the city, we see small and large initiatives in the improvements of streetscapes. Mass-transit, while it sputters, is gaining traction with major initiatives in clean and sophisticated bus systems, which add to the progress of light rail and metro transportation. To the surprise of many skeptics, new zoning initiatives that encourage mixed-use, transit-oriented development are being realized from Pasadena to Hollywood and beyond.

Developers who might never have considered taking on urban infill, mixed-use, or street-oriented retail projects are gravitating to the city in numbers we have not seen before. While the classic urban problems of traffic, environmental quality, affordable housing, good schools, and social and economic equity are all clear and present challenges, Los Angeles appears to have a real chance of evolving into a city not only of private choice, opportunity, and creativity, but of diverse and dynamic public opportunity and urbanism.

Los Angeles: Density with Intensity?

Doug Suisman, FAIA, is principal of Suisman Urban Design in Los Angeles. He is the lead author and designer of The Arc: A Formal Structure for a Palestinian State (RAND: 2005), winner of a 2006 national AIA Honor Award.

From the air at night, Los Angeles is as stunning as a pointillist painting—millions of separate dots adding up to a luminous tapestry. But on the ground, the dots atomize into an often disappointing landscape of parking lots and drive-ins. In Sondheim’s musical, Sunday in the Park with George, a jealous rival points to a painting by the pointillist Seurat and mockingly says: “It has no passion, no life—just density without intensity.” Critics of Los Angeles have often said much the same thing, except they have assumed the density was missing as well.

No more. According to the Washington Post, the 2000 census shows that the Los Angeles urban area is now the densest in the country. At 7,068 people per square mile, L.A. out-densifies metropolitan New York by 25 percent, doubles Washington, quadruples Atlanta. So the density exists—but what about the intensity? Is there passion and life in the streets of Los Angeles? Even with all those people packed together, is L.A. urban yet?

The conventional benchmarks for such urban intensity—tall buildings, tight spaces, honking taxis, and sidewalks packed with people—can be found in certain L.A. districts, but, like Seurat’s dots, they tend to be disconnected (at least for those on foot), leaving stretches of dead space in between. The discontinuity and fragmentation are due in part to the city’s vast expanse (a vastness actually exceeded by New York’s); to the still strong allure of the verdant suburbs and their laid-back lifestyles; and to more than 100 years of nearly hypnotic accommodation of anything the automobile demanded from an entranced population and its civil service engineers. This too is changing.

The land has pretty much run out, as the city hits the walls of the Santa Monica and San Bernardino mountains, and the talk is everywhere of “infill,” which is code for packing more people onto existing urbanized land. The talk is also of “mixed use,” which means there’s a growing market of people willing to live above the store, trade a backyard for a balcony and, god forbid, occasionally take the bus or train.

Does this mean a sudden explosion of intense urbanity? No—you have to go to China for that. It does mean that L.A. is palpably intensifying within its existing frame. While residential neighborhoods are limited to modest increases in density, the boulevards are springing to attention. Typically undercooked, with low-rise commercial buildings and parking, boulevards are sprouting ingenious new building types from three to fifteen stories, well crafted architecture with urban ambitions, much improved signage and streetscapes, and even, in some segments, a bunch of people actually walking around. Where two boulevards cross and produce one of the “nodes” so beloved of planners, bus and rail stations are appearing next to mid-rise apartment buildings with shops, producing a subtle but perceptible uptick in sidewalk activity.

In the big momma of nodes, “Downtown,” several billion tax dollars have produced a credible hub of regional mass transportation. Long neglected, steel-framed, terra-cotta clad treasures on the avenues are being converted into lofts, bolstered by a clutch of shiny new housing soaring to fifteen, thirty, or even fifty stories, either planned or in construction. They’re grounded by streetfront shops and even a new supermarket—the first in a generation.

Whether all of this intensified density and sporadic urbanity means that passion and life will spill onto L.A.’s boulevards in some form other than the scenes in Crash remains to be seen. The next generation of screenwriters will surely let us know—stay tuned.

The Los Angeles River: Our Future

Deborah Weintraub, AIA, LEED AP, is chief architect and Deputy City Engineer for the City of Los Angeles.

The Los Angeles River is a western river, flashy with winter rains, most of the year a dry bed. Flooding and development pressures led to its channelization in the 1930s and to its current condition as an ignored water right-of-way, which passes by the backs of property, offering almost no civic value other than flood control. The alignment of many interests has led to the current effort to master plan a revitalized river through the City of Los Angeles and to reclaim this resource for the region. I am fortunate to be helping to lead this effort.

Touring the Los Angeles River by helicopter is, at this moment in time, the best way to imagine the linear park—the green spine—that would connect the city’s neighborhoods and eventually extend through neighboring cities to the south to the ocean in Long Beach. As the helicopter circles downtown and comes up from the south, the historic Merrill Butler bridges in the downtown reach are spectacular examples of “City Beautiful” infrastructure that have been aesthetically isolated in the barren, concrete-lined flood channel, with railroads and warehouses lining the river. At Chinatown, the open site commonly known as the Cornfields is full of potential as a new state park in a “River District” that could extend from Chinatown to the river to the east, and could recall the origins of Los Angeles, as the city’s first water infrastructure (the Zanja Madre) passed through this area, drawing water from the river.

At the confluence of the Arroyo Seco and the Los Angeles River, the amount of publicly- owned land allows one to imagine greened open space, new housing, and community facilities. A connection across the river here to Elysian Park could join to a bikeway that would extend up the Arroyo to Pasadena.

At Taylor Yards, the remaining rail land adjacent to the river would permit the river to widen, supporting restored wetlands that could provide natural habitat in the heart of the city. Just to the north, you fly over the soft-bottomed stretch of the Glendale Narrows, which already attracts birds and supports in-channel vegetation. The adjacent industrial uses have traditionally turned their backs to the river, but the local residential neighborhoods have understood the value of this piece of nature. A river walk along this area could connect via pedestrian bridges across to Griffith Park and build a green river edge with cafés and lookout points.

Around the corner in the San Fernando Valley, existing open spaces could be reconfigured to address the river and to embrace water during high flows, recreating the natural attributes of the river. As the river passes through mostly single-family residential fabric in the San Fernando Valley, it is possible to preserve this residential fabric and to green the channel and the adjacent easements. Underused commercial property next to the river could be new development facing a reconfigured river walk.

These are just a few of the opportunities being discussed, and, with the cooperation of the Army Corps of Engineers, the Department of Water and Power, the County of Los Angeles, and others, our dialogue has been amazingly open and visionary. The helicopter tour brings home the potential of the riverway to knit the city together, to reinforce existing urban neighborhoods, and to create new river-focused environments that would add richness to our city. We have seen this happen all around the world with other river projects, and our opportunity to transform our waterway is coming.

There is a river in Los Angeles, and in my lifetime it will be transformed.

Richard W. Thompson, AIA, AICP, Principal in Charge of Urban Design and Planning at AC Martin Partners, has lived in an historic fire station in downtown Los Angeles for the last eleven years and has been involved in the revitalization of downtown L.A. for over thirty years.

Unlike its European and East Coast predecessors, and certainly unlike any city in Asia, Los Angeles grew up accommodating the automobile. Its network of freeways, perhaps the greatest in the world, circles its downtown core and radiates to its suburban communities. Ironically, it is the very strength of those freeways that has diminished the importance of downtown Los Angeles as the focal point of business, and certainly as a place to live. As a result, despite its uniqueness as an urban prototype, L.A.’s downtown is strangely like every other downtown across the United States—struggling to redefine its role in a modern urban society where accessibility is defined more by telecommunications than by wheels.

Over the last ten years, L.A.’s downtown has begun to reinvent itself through the convergence of a series of major landmark projects followed by a huge influx of urban housing. While each of the major projects was significant in itself (Staples Arena, the L.A. Cathedral, and the Walt Disney Concert Hall among others), their power to reinvigorate downtown was in their collective change of focus from office to cultural/entertainment uses and in their ability to change the perception of downtown as a destination within the region. This change in perception in turn finally laid the groundwork for downtown to become an attractive location for housing.

In the early 1990s, Los Angeles was experiencing a deep recession. The downtown area was particularly hard hit: its primary real estate focus was on office space, but there was a huge inventory of vacant older historic buildings, and businesses were rapidly fleeing to suburban centers. The Central City Association (an association of downtown business leaders) realized the time had finally come to address two issues: the shortage of housing in the region, particularly in downtown, and the vast inventory of vacant and underutilized building stock already in place. What better way to address both issues than to reuse these older buildings for housing? The idea was not new—other cities have accomplished major revitalization efforts by encouraging housing. But in Los Angeles, this idea had never taken off in any meaningful way, due to added concern with seismic safety and archaic and complex building codes.

A new “Adaptive Reuse Ordinance” was designed to ease regulatory requirements and encourage the conversion of downtown’s vacant building stock to housing. This single regulatory act has largely been responsible for the current boom in residential construction.

Since 1999, almost 7,000 residential units have been rehabilitated or newly constructed. Another 100 projects totaling over 9,400 units are under construction or at the permitting or planning stages. By the year 2015, 26,500 residential units are projected for development in downtown Los Angeles.

City officials have recognized the importance of connections to and within downtown and are preparing plans to invigorate the Grand Avenue and Figueroa Avenue corridors, with more than $5 million in public and private commitments for streetscape, local transit, and other physical improvements.

Regional attractions, urban housing, street retail, and pedestrian-friendly streets are finally arriving in downtown Los Angeles, creating the long-envisioned, around-the-clock vitality of people who actually live there—making that magic where the total is more than the sum of its parts.

Dashboard Reflections

Liz Martin is a founder of A+D Architecture and Design Museum in Los Angeles and principal of alloy projects.

Timing, that’s what Los Angeles is all about, timing. How far is it from Silver Lake Boulevard to Virgil? During rush hour, it could take twenty to thirty minutes to go ten blocks, but on a good day probably five to ten minutes if you’re able to time the lights. Distance has become obsolete in L.A.

Nothing is more fitting to the Los Angeles experience than driving. With its massive freeway system and lack of a decent and accessible transit system, Los Angeles is a region where one cannot survive without an automobile. Yet, with its increasingly overcrowded environment, driving around the southland can prove to be quite a hassle. Nowhere is the argument between car lovers and car bashers more salient than Southern California, a corner of the world synonymous with both the agonies and ecstasies of the automobile age. This is the place where an exhilarating Sunday drive on the curves of Mulholland or Sunset Boulevard can be followed by weekdays spent imprisoned in rush hour traffic. Driving in L.A., you quickly begin to understand the “hidden languages” of driving and gain insight into the “laws of survival” on the road.

Avoid stop-and-go traffic at all costs: it is the reason road-rage was born. Be polite to all those other stressed-out jacks on the road, because they will follow you. And you do have to go home eventually. Is road-rage hyped media or reality? Hmm… a bit of both, but anyone with claustrophobia should not even think about driving in L.A.

For me, if I cannot take the Red Line to my destination, surface roads are the way to go. Once you’re off the freeway, you can catch up on your phone calls, listen to your favorite album, or simply contemplate. Who ever has time to think anymore? I do… and in my car. Dashboard reflections are my favorite L.A. pastime. Driving by those sexy billboards along Sunset Boulevard, I learn almost all there is know about pop culture, current trends, and vanity.

In the early ‘80s, having a trainer was the rage. Gyms popped up on every corner, along with big billboards trying to lure you in as you drove by. Then, with the self-help ‘90s, everyone had a therapist, later moving on to a life coach, but only after a life-changing yoga experience. There was a very brief moment around the turn of the millennium when some folk were getting a personal concierge. I never even understood that one!

Now, driving on Sunset, I’ve learned it’s time to move on to the next vanity experiment, one that will give us all material for dozens of dinner-party conversations to come. It’s time to track down your own personal “hair coach”—fashion astrology at its best. A hair coach’s services look too attractively absurd to resist. I might actually jump on the bandwagon this time!

An Exaltation of Cars

D.J. Waldie is the author of Holy Land: A Suburban Memoir and other books about Los Angeles.

Riding through another L.A. night on an MTA bus that takes nearly two hours to traverse the string of immigrant neighborhoods from Boyle Heights to North Long Beach, I don’t see any of the middle-class commuters the transit authority hopes vainly to lure from their cars.

On the night bus, only tired working people are on display. Unlike motorists at night, who are invisible inside their cars, bus riders travel in the glare of overhead lights that turn the bus windows into showcases washed in hard, greenish yellow.

The motorists outside are oblivious, though, wrapped in their second skin of automotive PVC, safety glass, and sheet metal. They won’t ever see, as I have on the night bus, the civil gesture of the tall, young black man toward the old, white man whose leg he must brush aside to pass down the crowded aisle, a light double tap with the side of the young man’s hand on the old man’s shoulder and a word of excuse answered with a nod, the old man’s mild face half turned to the young man.

We’re the ones always at the periphery of your gaze, if you’re an L.A. driver. We’re the transit dependent who stand in a shelterless cluster of five or six at the intersection where you’ve just turned right on red without even slowing.

As you turn, the most anxious one among us, who had been peering in hope into the on-coming traffic, steps back from the curb, a bulging discount store bag digging a red band into the flesh across the back of the hand she had thrust through the plastic handle (that red line across a numbed hand is the pedestrian stigmata).

And the most resigned one of us hangs back, leaning his left shoulder against anything (a light standard, the stucco wall of strip mall, a struggling tree), his head down and hands jammed into the pockets of a drooping jacket, and the rest of us in anonymous poses of silent attendance on the traffic bunching and flowing in its minute-long systole and diastole as the lights change green to red on the imperial grid of Los Angeles, none of us observing with anything like the exaltation it deserves the glowing arc of bright cars turning left against the flow of traffic, as lovely and self-possessed as the line of dancers in a ballet.

Erik Lerner, AIA, is an architect practicing as a Real Estate Broker in Los Angeles and on the Internet at www.RealEstateArchitect.com.

My house is vibrating. The windowpanes are rattling, the mini-blinds are fluttering, and the floor is bouncing. Elsewhere it might be a passing subway train. Here these are familiar symptoms of an incipient earthquake. Fault-zone conditioned, I prepare to take cover. But the shaking doesn’t come.

Instead, there is the mechanical sound of a helicopter engine outside. In this far-flung town with a low ratio of police officers-to-square miles, aircraft keep tabs on fleeing suspects until the squad cars catch up. But on this night there are no sirens.

The TV picture is flickering to the rhythm of the rotors overhead, distorted by the airborne interference. Viewers worldwide are seeing the same thing as I, except without static: live aerial video of my neighborhood.

It’s Oscar night, and two post-ceremony parties are getting underway nearby. The Vanity Fair party is at Morton’s, down Robertson at Melrose. Elton John is holding his annual AIDS fundraiser at the Pacific Design Center over on San Vicente. The choppers are covering the story.

Crash has won best picture. In the film, a character muses about L.A.’s legendary isolation: “In any real city, you walk, you know? You brush past people, people bump into you. In L.A., nobody touches you. We’re always behind this metal and glass…”

I step out the front door for a closer look. The street is lined with trees and cars. Otherwise, save for a woman and a dog, it’s deserted, as usual. Down at the end of the block, though, the boulevard is bumper-to-bumper with party-bound black limousines. In the distant sky, a caravan of jets floats silently over the vastness toward LAX. A smaller plane buzzes low on its way to Santa Monica airport. Party sounds and traffic noise mix in the air. Over my neighbors’ rooftops, the news-copters hover, collecting celebrity video. Behind them, the silhouette of the Hollywood Hills twinkles with the lights of a thousand houses. Close by, searchlights scan the dark sky.

It’s a cool night in L.A. I button up my coat and start to walk.

L.A. Shortcut

Rana Cho was born in Los Angeles and has called home Seoul, Providence, and Berkeley. She is cofounder and principal of Gingerworks, which provides qualitative research and brand strategy.

Navigating Los Angeles requires a lexicon of intersections, numbers, and cardinal points.

How does one get to this nomenclature? Sunset and Vine, Third and Fig, 710-North, 5-South. It’s shorthand for L.A.’s meridians. Critical while interstate and Port of L.A. traffic increases, no new freeways planned for the next ten years.

Times like these, when time and space seem in short supply, shortcuts are valuable. And what are shortcuts but the reuse and revision of an existing path? One man’s discovery of a shortcut is another’s everyday routine.

During a condo conversion project, local interviews yielded this insight: Koreatown is a wealth of local surface road shortcuts (Olympic, Pico, Vermont) bypassing the heavy 10, 101, and 405 freeways. The major shortcuts, Western and Wilshire, intersect each other in the heart of Koreatown. Streams of Asian restaurants, car lots, strip malls replace freeway scenery. What does an L.A. shortcut look like?

What’s at Western and Wilshire? The resurrected, Art Deco, giant Wiltern. An unearthed subway station. And a white, twenty-two story building so typifying the modern that it has been everything and nothing: a vocational school, bank, numberless small businesses.

Yet, the white building originally commissioned for the Getty Oil Company headquarters sits on Hollywood history: Both Rebel Without a Cause and Sunset Boulevard were filmed here.

This is the intersection of fire during the 1992 Rodney King riots. This is the intersection in dispute during the early ‘80s redistricting of L.A.’s minorities. To the west, Hancock Park, the oldest Jewish community in L.A. To the east, the Alvarado corridor that seems to have a tunnel straight to Mexico. Southward lies Compton, and the 101 blocks the northward ascent toward the hills.

Instead of a shortcut to Hollywood, Santa Monica, or Pasadena, Los Angelenos are finding shortcuts to home by living at the intersection. These shortcuts, once places of passing, are early anchors committing this city to its communal grid.

The shortcut to the future is the present.

Our Los Angeles

Yareli Arizmendi is a Mexican-born actress, writer, and producer who has lived in California since 1983. She played Rosaura in the film Like Water for Chocolate, and wrote, with her husband, Sergio Arau, and Sergio Guerrero, the 2001 feature mockumentary, A Day Without a Mexican, in which she played the lead role of Lila Rodriguez.

—Have you been to Los Angeles?

—The city?

—No, the set.

Welcome to my city, where the people, the buildings, even the sun are willing and able to accommodate the camera. We live in a city dangerously comfortable with constructing realities that “hold” only long enough to trick the eye. We starve ourselves so the lens won’t make us fat, not noticing that in real walking-life we look emaciated. But who cares about the here and now when the camera teases and dangles the key to forever… to immortality?

And so our industry of dreams goes on to colonize the psyches and expectations of people on the receiving end of our images, too far away to hear the deafening sounds of the swing crews striking down the West Wing of the White House—the set, that is.

“Heretodaygonetomorrow” is our mantra. Impermanence lends all who arrive in Tinsel Town permission to build and to destroy, as long as we promise to put up the “next big thing.” In a town that fears the old and used, we applaud and admire those—the plastic surgeons, art directors, architects, advertisers, designers, lawyers even—who can recreate a reality down to its minute, desirable detail, while conveniently leaving out those deemed not so attractive. Experiencing the original, the unaltered rawness of the real, is rendered dispensable: too imperfect for the camera and posterity.

But we, in our quest to “matter,” race against erasure. With little awareness or respect for what has come before, we rush to tag the town with the bold “I was here” that we hope will outlive the next coat of paint. Few make it, cross over into immortality with that one film, book, or scandal that rings the town’s overnight success bell. Entering the Winners-and-We- Know-It Club, they move to the hills, out of reach and out of touch.

And the others, left outside, do we keep trying? Do we desist, or do we go on to make Los Angeles our home, a place to raise our children and grow old? The faint calling of “the flats” grows louder.

Our freeways—that cruel joke Detroit played on us—have rendered Hell-A sprawl, arms and legs that lead too many places and none. But the surface streets, leading someplace, whisper, begging to be discovered. We are their hope. As we debate “should I stay or should I go?” we jump in the car—our weapon of choice—and get off the roads most traveled: the 5, the 10, the 405. Willing to not know where we’re going, we take time to peep behind the walls that line the boulevards and avenues, suddenly discovering where we’ve stood but never really been.

There before me is a monument to a misunderstood L.A.: On the outside, a nostalgic recreation of someone’s Koreatown pagoda, once majestic, now faded, it hardly calls attention to itself. But take the time to go inside and let the color walls blast you awake: yellow, magenta, blue. “La Guelaguetza,” pagoda-turned- Oaxacan-Mexican restaurant, is at home with its fused destiny. And so are we: this is our Los Angeles. The city.

Ripped Open Like a Bag of Potato Chips

Scott Saul, an Assistant Professor of English Literature at UC Berkeley and author of Freedom Is, Freedom Ain’t: Jazz and the Making of the Sixties, is currently working on Just Enough for the City: Black Arts and Black Life after Watts.

Some people love L.A., some people hate L.A.—and then there are those (many L.A.- based artists and intellectuals among them) who love to hate L.A., who find a perverse pleasure in scrutinizing the city’s dark carnival. Between the boosters and the debunkers stand the boobunkers. I think I’m among them.

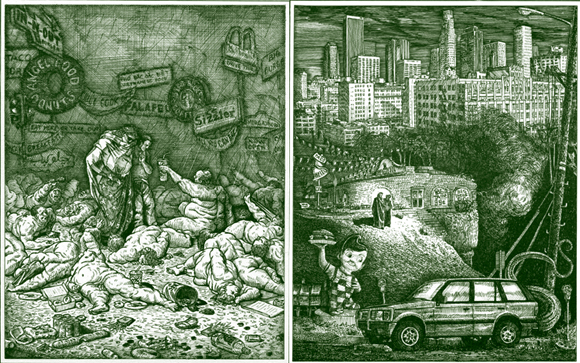

I’m led to such thoughts by Sandow Birk and Marcus Sanders’s recent edition of Dante’s Inferno (Chronicle Books, 2004), which renders the medieval Italian’s descent into hell as a guided tour of a grotesquely noirish Los Angeles. Half-dispiriting, half-hilarious, their Inferno translates Dante’s Florentine dialect into surfer-skateboarder vernacular, taking considerable liberties along the way (e.g., “I saw a sinner who had been ripped/open like a bag of potato chips or Cheetos”). Its narrator—as depicted in Birk’s gloomily detailed etchings, where every cross-hatching seems touched with grime—wears a hoodie, baggy pants, and a perpetually harassed expression, as if he had no idea what he was in for.

What he sees—what Birk’s imagination offers—is a hyperbolic extrapolation of L.A.’s extreme class divides and its dizzyingly commercial landscape. The company of hell’s hypocrites (forced to wear leaden shawls that make them move “slower than a tai chi class”) is dominated by businessmen with briefcases and members of the L.A.P.D. Gluttons writhe naked on a street littered with pizza cartons, doughnut boxes, Big Gulps, and KFC buckets, while the signage of McDonalds, the Sizzler (“all you can eat”), and In-N-Out suggests how they (we?) got in this mess. The giant Antaeus appears as a huge inflatable-balloon Fred Flintstone, ever-cheerfully lowering Virgil and Dante into the deepest pit of hell. The moral of the story—we are amusing ourselves to death—is disclosed to the viewer with a cunning smile.

For all their keen interest in imagining L.A. as literally hell on earth, Birk and Sanders should not be classed with those who bash L.A. from a place of moral superiority: slackerese is not the voice of the high-and-mighty. There are smaller self-critical gestures too: throughout the book, Virgil’s own cloak is decorated with a variety of commercial snippets (the Dodgers logo, “WAXING FACIALS PEDICURES”), and one telephone booth even sports an advertisement for the DVD edition of an earlier Birk project, winking at the artist’s own participation in a culture of buzz.

Will we, like Dante, emerge from our sojourn in this infernal L.A. and, in our wised-up and chastened state, be able to glimpse the stars? I’m hopeful that artists like Birk and Sanders can help us see more clearly the nightmare that Los Angeles has become, is still becoming; and I would like to think that the realms of purgatorio and paradiso will not be too far off, especially for those who suffer most rudely the city’s injustices and inequities. Unfortunately for Angelenos, though, Birk and Sanders will not be our guides to this higher ground. They set their Purgatorio in San Francisco, their Paradiso in New York, leaving boobunkers such as myself to wonder at the limits of our critical imagination.

Getting Out

Jay Mark Johnson is an artist and writer living in Venice, California. His photographs appear throughout this issue.

I can’t seem to keep both feet on the ground in Los Angeles. I’ve been living and laboring here for fifteen years and I still don’t think of it as home.

Part of the problem is the landscape. It’s so sparse. Sure, there was a river, but it was never a Fertile Crescent. Take away the buildings, roads, and irrigation systems, and the basin will return to dry scrub brush, with a thin line of craggy mountains in the distance, perhaps a few damp spots here and there. And a tar pit. Everything else is wide open to the sky. Death Valley by the Sea might be great for the motion picture industry, which loves small apertures, fast shutter speeds, and a clean-swept stage, but it does leave one pondering the rest of the city’s history. Why here?

Another difficulty for me is an unsettling condition that results from the confluence of two greater problems of the built environment. When a dearth of history is combined with unchecked urban expansion, the result is an indecipherable entanglement of street grids and boulevards, of clover leafs and shopping malls, of gas stations, billboards, road signs… How does one make sense of it? How do you navigate through it? Where are the markers on the landscape? Where are the centers? Where is the recognizable skyline?

Try to think of a single image that represents Los Angeles. Blue skies framed by evenly spaced palm trees? Polished pink stars on a pebbly gray sidewalk? An eighty-year-old real estate sign? Those images are all tight “close ups.” Where is the wide shot? Where is the iconic cityscape? Wide, panning shots of L.A reveal its flat, chaotic, brutally routine sprawl. Like a soundtrack composed entirely of background noises, the pieces fall haphazardly together into a singular indistinguishable cacophony. No dialogue. No soloists. No virtuoso. White noise with smog.

In recent weeks, I have traveled to a number of cities that are enduring the world’s most uprooting cases of explosive urban sprawl— Shanghai, Bangkok, Vancouver, and Las Vegas. None of them seems to have a clear idea of what to do. Each of them may in fact be losing both the battle and the war. But each benefits from a distinct character and a readily recognizable identity drawn from a combination of its landscape, its history, and the fantasy employed in the construction of its most prominent new structures.

Like so many of the world’s cities, L.A. has plenty to deal with in addressing the complexities of a runaway metropolis. And the city could definitely benefit from a few well-conceived, even interventionist, urban design projects. But unlike what is accomplished every day in the movie industry, the city is unable to fabricate, instantaneously, a more rich natural setting or a more entrenched history. It might nonetheless employ on the broad urban landscape what it uses to great effect on the giant silver screen: pure artifice.

Tinsel Town needs an improved skyline, more vested urban centers, and a distinguishing posture on its landscape. If in the next few decades it can build up its centers and cut back on its cars while keeping the whole place from going underwater, it might be worth sticking around for. Or at least coming back for the occasional visit.

Shaunt Yemenjian is a graduate architecture student at the Southern California Institute of Architecture. He is particularly interested in studying architecture as a means of shaping and promoting culture. He believes that architecture can be aesthetically pleasing but must first be responsive to be considered great.

Resembling the web-like pattern of inbound flights to an international airport, most U.S. architecture students must first make their way to a major metropolis to pursue higher education. Unlike international travelers, however, students often find difficulty in making it back to their point of origin—physically.

The local practice paradigm has changed over the past twenty years, with advances in modern telecommunications. We now have the capability of visiting sites “virtually,” sharing drawings online, communicating at high speeds with consultants, and so on. These advances have given us the ability to live in Zurich and build in Las Vegas. Adapting this model to domestic practice has allowed more architects to pursue small town commissions without actually having to move back home. In essence, it allows young architects to make their way back to their point of origin—virtually.

Each year, towns like Peoria, Ashville, and Eugene lose aspiring architects to cities like New York, Boston, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. We need not look beyond California for evidence of this phenomenon. At the Southern California Institute of Architecture in Los Angeles, over one-third of the student body (480 students) comes from out of state, and nearly one-half of the students in the architecture program at the University of Southern California (625 students) are not from California. This phenomenon is confirmed by an informal survey conducted on the SCI-Arc campus. Last semester, of seven out-of- state students in studio, six plan to stay in Los Angeles. This semester, seven out of nine plan to stay. SCI-Arc estimates that roughly 70 percent of graduates from the last five years have remained in L.A.

The issue, though, is not the departure of future architects, but rather that many of these small towns end up filling the gap of designers by looking elsewhere—selecting from a pool of “virtually local designers.” Any city, small or large, should not be forced to compromise design quality as a result of an architect’s lack of familiarity with new territory. Responsive design is rooted deeply in its environment, culturally, politically, historically, and otherwise. The challenge we face as young architects is to invest the time and energy in learning about the places where our work will take us, so that design can reflect the community in which we will work. Are we prepared to meet this challenge?

For a young architect, seizing each opportunity to learn, test ideas, and communicate is often the motive behind career decisions. Arguably, major cities are more conducive to these criteria, and so the number of architects returning to their hometowns after an L.A. education diminishes. But as opportunities arise, these “virtually local designers” will be given the responsibility to shape the small town built environment. They may have a bit of catching up—or remembering—to do to discern what shapes the character of a less well-known community.

Let’s not look up in twenty years and wonder whether we are in Peoria or French Lick.

Many Theres Here

Anne Zimmerman, AIA is Principal of AZ Architecture Studio in Santa Monica. She is on the Board of Venice Community Housing Corporation and on the AIA Documents Committee.

Imagine flying into Los Angeles for the first time and seeing the vast, homogenous, lightcolored expanse of buildings and roads, dotted with a pool here and there, some mountains through the smog. Reyner Banham’s Plains of Id… but not really.

Observe more closely, and you see that L.A. is an amazing warren of neighborhoods, with their own character, demographics, amenities, and often charming homes. (Not even counting the separate, unique cities that are within L.A. County but not in the City of Los Angeles: Beverly Hills, Santa Monica, Culver City, West Hollywood, Burbank, Glendale, Pasadena.)

There are so many heres in Los Angeles, you need a guide. Venice, for example, is rapidly gentrifying, although it retains much of its beach funky character, from the Boardwalk to Abbot Kinney to the pedestrian walks and canals.

Jeffrey Valance has his benign, appreciative, artistic view and Larry Sultan his not quite porn view of the San Fernando Valley, but a visit to North Hollywood brings you to a Thai street food market at Wat Thai on Coldwater Canyon near Roscoe. Here, enslaved Thai garment workers fled after they escaped their El Monte sweatshop/jail. Heading south on Coldwater Canyon and Lankershim, you pass a slew of good to very good Thai restaurants in mini-malls before the NoHo Arts District with street banners (!) and a critical mass of small Equity waiver theaters, cafés, and restaurants. You have to love the Emmy statue and courtyard in front of the new Television Arts and Sciences Building.

Leimert Park, often irritatingly referred to in the same breath as South Central Los Angeles, is a part of the Crenshaw district. This area was planned in 1928 with the assistance of the Olmsted Brothers and is an off-the-grid triangular pocket of park, homes, and apartments with a small business area nurturing black-owned and Afrocentric businesses, cafés and music clubs. A drum circle on Sunday afternoon in the park sets the tone. Unfortunately, Phillip’s Barbeque is not open on Sunday!

Atwater Village, nestled between the L.A. River and the Golden State Freeway (I-5), has a business center along Glendale Boulevard with views to the San Gabriel Mountains and Griffith Park across the river. This neighborhood feels like a small town complete unto itself with bucolic homes, businesses, and pace. How wonderful if the L.A. River became more accessible here.

Cesar Chavez (formerly Brooklyn) and First Streets in Boyle Heights are a bustling Latino marketplace. The area has experienced dramatic shifts from multi-cultural and Jewish to Japanese-American to its current Latino multi-cultural community. The Breed Street Synagogue—the last remaining of twenty-seven synagogues in the neighborhood—is being restored. Mariachi Plaza attracts musicians for hire, and there are restaurants galore, including the upscale Serenata di Garibaldi.

Other neighborhoods well worth the wander include:

Chinatown: Cornfield park-to-be, Chinese and Vietnamese restaurant community.

Highland Park: Southwest Museum (Native American treasures), Lummis house El Alisal (arroyo stone).

San Pedro: the Port of Los Angeles, very Jack London, Mexican-style seafood overlooking the port and on weekends Mariachi music at Ports O’Call.

Silver Lake: alternative rock music, cafes, restaurants, vintage clothing and furniture stores, Neutra, Schindler, and more architecture.

With the Lonely Planet Los Angeles, David Gebhardt/ Robert Winter’s Los Angeles: an Architectural Guide, Reyner Banham’s Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies, Charles Moore, Peter Becker, and Regula Campbell’s The City Observed: Los Angeles: a Guide to its Architecture and Landscapes, and a Thomas Guide, you have it made.

Originally published 2nd quarter 2006 in arcCA 06.2, “L.A.”