The twenty-four-hour life of the urban fabric of our communities is affecting not only the natural environment, but human health and well-being. As noted by the U.S. Green Building Council, buildings in the U.S. consume more than 30% of our total energy and 60% of our electricity. The U.S. consumes 5 billion gallons of potable water per day just to flush toilets. A typical North American commercial construction project generates up to 2.5 pounds of solid waste per square foot of floor area. Sustainable design practices can substantially reduce these negative environmental impacts and reverse the trend of unsustainable construction practices, but we must look beyond doing less harm to providing designs that heal the earth.

The California Architectural Foundation challenged architects, students, designers, planners, and all interested individuals to develop solutions to reduce the environmental impacts on our planet, slow urban sprawl, and discover innovative ways to effectively reuse existing resources. The aim of the competition was to examine strategies that not only minimize the footprint created by the construction and ongoing operation of a project but reach beyond to heal the damage inflicted by less sensitive development.

The Brief

The competition sought sustainable solutions for urban infill projects with a zero carbon footprint. The site is an approximately sixty-acre parcel located in Visitacion Valley on the San Francisco Peninsula. Just west of Highway 101, it is bounded by Bayshore Boulevard on the west and Tunnel Avenue to the east. Landmarks in the neighborhood include Candlestick Park on the shores of the Bay to the northeast and the Cow Palace to the west. The area is surrounded by a broad variety of residential, commercial, and industrial uses. Only a short distance from both downtown San Francisco and the high-tech environment of Silicon Valley, there are an abundance of resources available for creative development.

A previous study of this site had yielded a planning overlay that outlines a series of mixed-use commercial and residential overlay zones. A current Planning Department study also outlines a conceptual open-space network, to be taken as a guideline and not a requirement—commitment to public access to open space is the underlying issue. Consideration should be given to the scale of the surrounding community and how the proposed development will enhance the area beyond the immediate boundaries of the site. At the same time, it is expected and desired that this development be seen as a new landmark for all who pass on the nearby 101 freeway. Adjustments to scale and density that are supported by analysis based on the ability to better go “off grid” will be assessed to determine the eco-advantage of the increases.

A typical residential density in San Francisco is approximately 25 dwelling units per gross acre or 50 dwelling units per net acre. To achieve eco-effectiveness at a neighborhood scale, it was anticipated that the site might tend more toward the 50 to 60 dwelling units per gross acre density. A typical project in this area might be required to park the site at a ratio of 1.5 to 2 cars per dwelling unit on site; the competition developer was permitted, as an environmentally friendly designer, to work with a reduced parking requirement of .75 spaces per dwelling unit on site. That requirement could be further reduced with justification and narrative regarding how transportation will be handled through alternative means.

Achieving a “zero carbon footprint” is difficult on an individual dwelling or business scale. It becomes increasingly achievable as the design approaches a neighborhood scale. There is, no doubt, a tipping point where the density of development goes beyond the eco-advantages and slides toward over-development. It was incumbent upon the submissions to find that optimal point and to describe the way in which it can be quantified.

Criteria

Definitions of “sustainable design” vary and are subject to interpretation. To help clarify the most important principles, the AIA Committee on the Environment has developed its “Top Ten” measures for sustainable design, which entrants may use as a loose guideline: “Great design includes environmental, technical, and aesthetic excellence. Stewardship, performance, and inspiration are essential and inseparable.” (See the AIA Top Ten Green Project Metrics at http://aiatopten.org.)

The jury reviewed each submission on the basis of the multi-dimensional impact the ideas offer for re-shaping the way in which we create our communities. While components and systems need not have been wholly drawn from existing technologies, it was expected that the concepts are realizable within the near term. Inclusion of concepts drawn from ongoing research and the application of previously theoretical elements was encouraged. The goal was to stretch the imagination of all who are exposed to the concepts that emerge, leading our profession toward a carbon neutral future.

Eligibility

The competition was open to any California resident (including students who attend school in California, but may not be official residents of California).

Jury

Lance Bird, FAIA

La Canada Design Group, Inc.

Costa Mesa

Mary Griffin, FAIA

Turnbull Griffin Haesloop

San Francisco

Harrison Fraker, FAIA

Dean, College of Environmental Design

UC Berkeley

1ST PRIZE: Commendation Award

($2,500 plus $5,000 to the architecture school of the winner’s choosing, the College of Architecture and Environmental Design, Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo)

“Cascading Energy”

DES Architects + Engineers, Redwood City

Design Team:

Candice Lui

Tracy Wong

Howard Kwok

Chi-Wing Wong

Ginny Yi

Waibun Lee

Rico del Moral

Amy M. Strazzarino

Byron K. Wong

Enoc Lira

Cascading Energy is energy transferred. Wind becomes electricity. Electricity converts to a social vigor. Social vigor sustains an economic life. This new development is about creating, conserving, and sustaining energy in all its forms.

Visitacion Valley is the gateway to the City of San Francisco. At the threshold of this entry is a new architectural billboard declaring to the world that a sustainable urban community is possible and preferable. A dual-pronged approach is used to both generate energy and reduce consumption to neutralize the carbon emissions and environmental impact of the site.

The site tells us what it wants to be. It wants to be tall to take advantage of the high winds. It wants to be compact in design to reduce energy consumption. It wants to pay homage to its past as home of the former Schlage Factory. It wants to be connected to adjacent neighborhoods. It wants to use its open space to unite the community in festivals, to grow its own food, and to filter its own pollutants.

Energy transforms from a physical state to a communal vibrance to a cultural enterprise. The flow continues and energy cascades.

2ND PRIZE: Citation Award

($1,250)

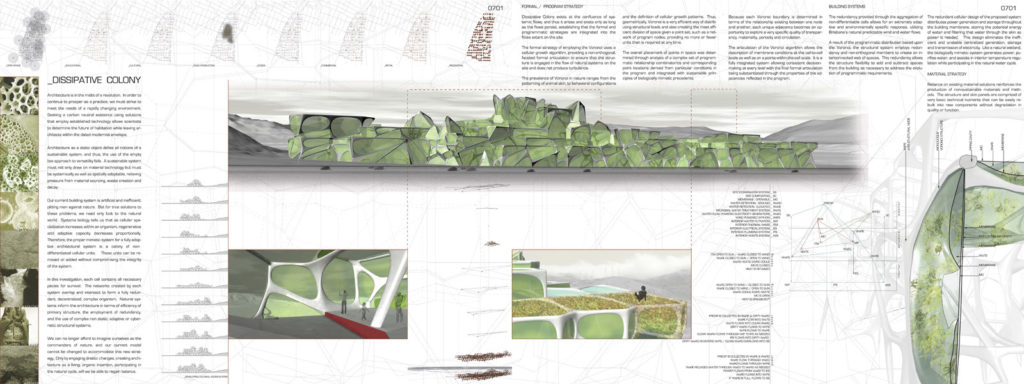

“Dissipative Colony”

Gray Dougherty, Assoc. AIA and Dan Sullivan, Albany

Architecture is in the midst of a revolution. In order to continue to prosper as a practice, we must strive to meet the needs of a rapidly changing environment. Seeking a carbon neutral existence using solutions that employ established technology allows scientists to determine the future of habitation while leaving architects within the dated modernist envelope.

Architecture as a static object defies all notions of a sustainable system, and thus the use of the empty box approach to versatility fails. A sustainable system must not only draw on material technology but must be systemically as well as spatially adaptable, relieving pressure from material sourcing, waste creation, and decay.

Our current building system is artificial and inefficient, pitting man against nature. But for true solutions to these problems, we need only look to the natural world. Systems biology tells us that as cellular specialization increases within an organism, regenerative and adaptive capacity decreases proportionally. Therefore, the proper mimetic system for a fully adaptive architectural system is a colony of non-differentiated cellular units. These units can be removed or added without compromising the integrity of the system.

In this investigation, each cell contains all necessary pieces for survival. The networks created by each system overlap and intersect to form a fully redundant, decentralized, complex organism. Natural systems inform the architecture in terms of efficiency of primary structure, the employment of redundancy, and the use of complex, non-static, adaptive or cybernetic structural systems.

We can no longer afford to imagine ourselves as the commanders of nature, and our current model cannot be changed to accommodate this new strategy. Only by engaging drastic changes, creating architecture as a living, organic insertion, participating in the natural cycle, will we be able to regain balance.

2ND PRIZE: Citation Award

($1,250)

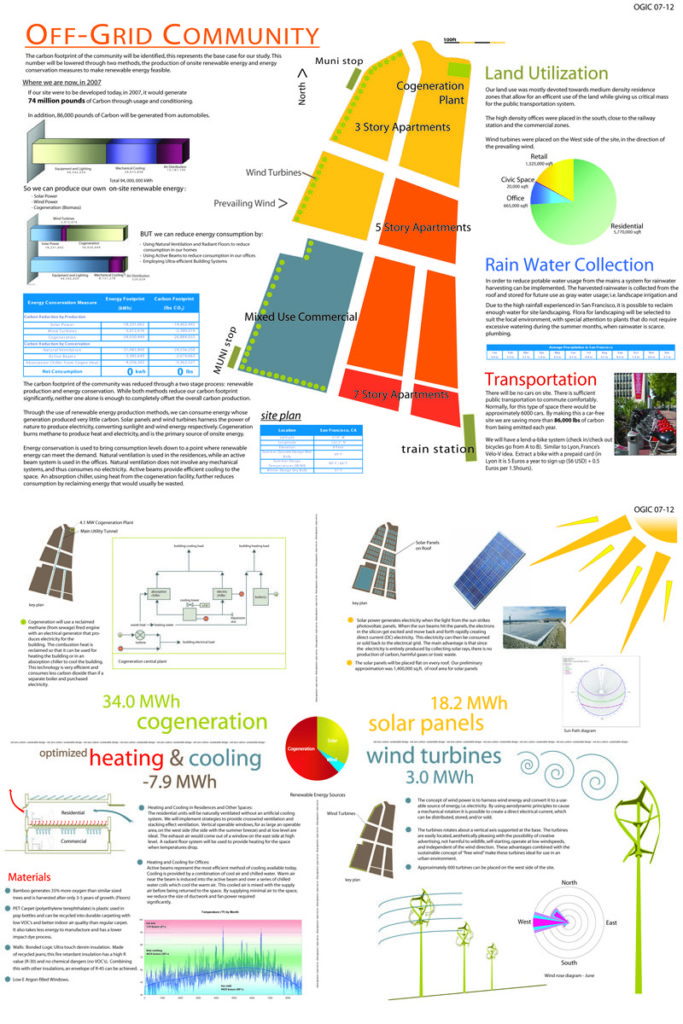

“Off-Grid Community”

IBE Consulting Engineers, Sherman Oaks

Design Team:

Danielle Krauel

Howard Ho

Peter Simmonds

Michael Leung

Neil Alexander

Christie Lyons

Isaac Chambers

Paul Baker

Patrick Wilkinson

Hong Gip (Cannon Design)

Passive Energy Conservation Building Strategies

• South side overhangs.

• High narrow windows to admit more useful daylight.

• Minimizing energy intensive commercial zones.

• Operable windows.

• Openings oriented towards the prevailing summer breezes.

• Taller buildings on the south side provide shading during the summer months.

• Natural ventilation.

Rapidly Renewable and Innovative Building Materials

• Bamboo floors and other finishes.

• Recycled PET Carpet with low VOCs and lower impact dye process.

• Bonded Logic Ultra touch denim insulation, made of recycled jeans.

• Double-paned, Low-E, argon filled glazing.

• Use of recycled and locally sourced materials.

• Reuse existing site materials.

Green Construction Practices

• Modular construction to reduce the waste generated on site.

• Recycling all waste, including day-to-day worker lunch trash.

• Site soil erosion prevention plan.

Promotion of Energy Efficient Transportation

• No inefficient cars will have parking on-site; limited parking provided for hybrid vehicles.

• Lend-a-bike system.

• Easy access to local mass transit such as the MUNI and Cal Train.

• Create an education program to bring green transportation to the tenants.

Efficient Resource Management

• Low-flow fixtures and waterless urinals.

• Rainwater harvesting.

• Drought-resistant flora.

• Gray water reclamation and reuse.

• On-site wastewater treatment before discharging to the sewage system.

• Recycling center.

Originally published 1st quarter 2008, in arcCA 08.1, “’90s Generation.”