Adapted from Practice with Purpose: A Guide to Mission Driven Design, by William Leddy, Marsha Maytum, Richard Stacy; ORO Editions, 2023.

The adaptive reuse and deep energy retrofit of existing structures is the most potent strategy currently available to rapidly decarbonize the built environment, now, when our planet needs it most. Existing buildings can be priceless repositories of both embodied carbon and embodied culture accrued over time, regardless of their conventional historic significance. They are long-term investments made by our communities – valuable resources that would be lost forever if demolished, contributing to the continued unravelling of the cultural fabric of our communities: their embodied history, their societal connections, and their resilience. When new resources are used to replace our existing buildings, the new carbon emissions they generate will contribute to accelerating global climate change during the next six to ten years – a critical period in the history of the global climate emergency. As the Architects’ Journal RetroFirst Campaign declared in 2019, “Where the choice is between demolishing to build new or retaining an existing structure, the default approach should be to retain and retrofit.”1

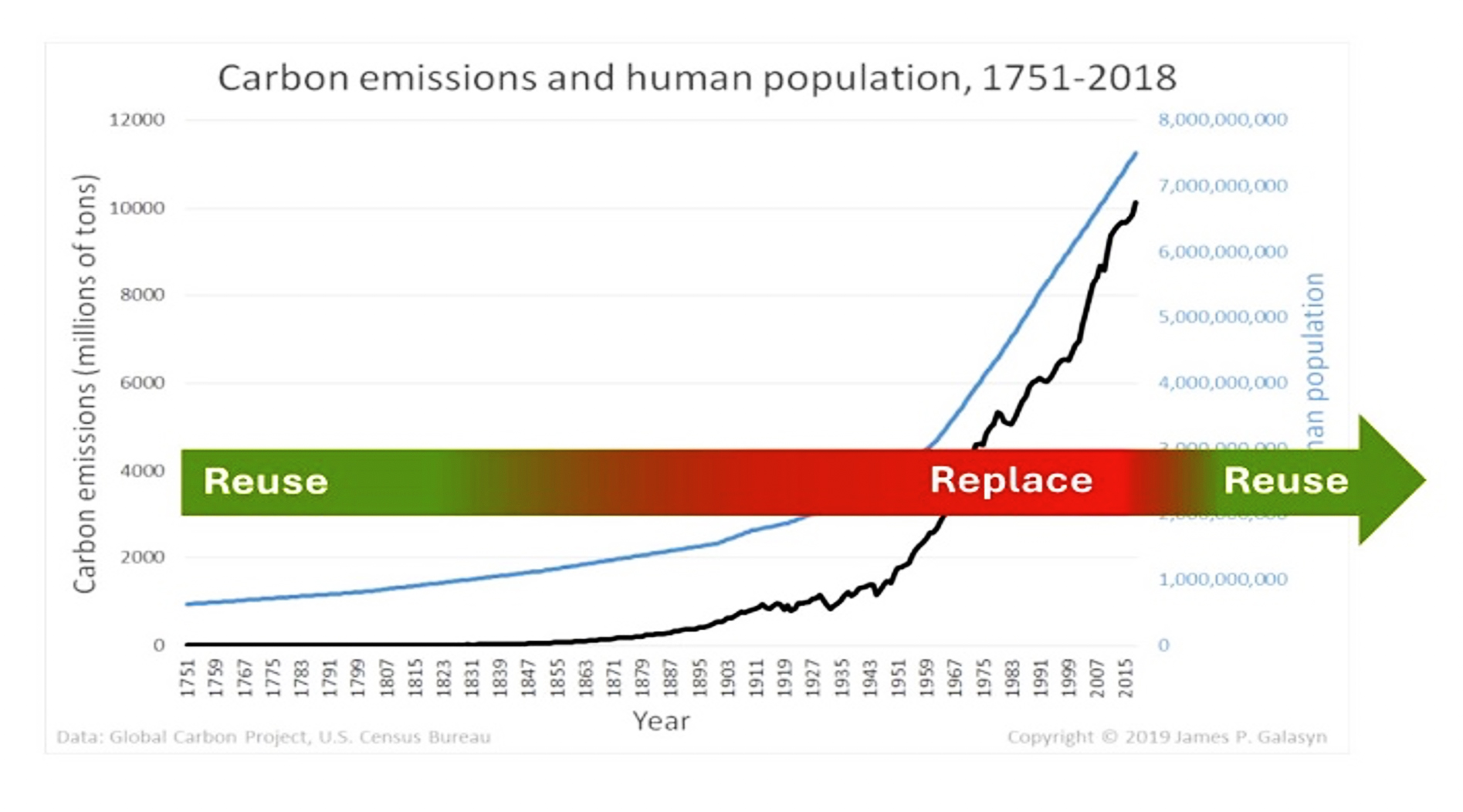

For centuries, a tradition of frugal stewardship of resources preserved, transformed, and reused existing buildings and their materials. The remnants of Roman amphitheaters were transformed into medieval fortresses and then, centuries later, into housing. Indigenous and vernacular architecture, from wood structures in Japan to earth structures in Mali, are rooted in generations of this tradition of stewardship of the land and its precious resources – traditions that have all but disappeared.

Since the dawn of the industrial revolution in 1760, the global population has exploded from seven hundred million to 8.1 billion, a growth rate powered by burning fossil fuels, which in turn fostered a shared delusion – at least among industrialized nations – of limitless natural resources fueling never-ending growth. Now, as we awaken to the post-carbon age, society’s continued extraction, destruction, and profligate exploitation of earth’s resources must be quickly transformed into “reuse, reinvent, and repurpose.”

The enormity of the global climate emergency is so overwhelming that it is difficult to grasp how one individual can make a difference. But architects are uniquely qualified to do just that. We have the design vision and technical knowledge to transform existing structures into high-performance, resilient, zero-carbon buildings. The embodied carbon impact of renovating an existing structure is 50–75% lower than that of constructing a similar new building of the same type and scale.2 Performing a deep energy retrofit of reused buildings doubles the impact of carbon reduction by retaining the embodied carbon value of existing materials, and by significantly reducing operational carbon emissions through high-performance system upgrades and renewable energy resources.

Benefits

Approximately 96 billion square feet of commercial buildings3 and 236 billion square feet of residential buildings exist in the US.4 Adapting and reusing these massive resources offers multiple benefits beyond carbon emissions reductions:

Environmental: Enhanced resource conservation; reduced demolition waste sent to landfill; improved air quality, both internally and externally, due to less impactful demolition and construction processes; and significant energy savings, resulting in greater energy security.

Economic: Increased value of real estate assets; reductions in project public approval timelines; significant savings in construction costs (when compared to a ground-up building) and operational costs; and job creation within local economies, especially in disadvantaged communities. According to the AIA, restoration and adaptive reuse of existing buildings already accounts for over 50% of all U.S. architecture billings– a market that is expected grow in the coming years.5

Social: Improved health and well-being, safety and security; greater continuity of cultural and historical connections, which results in greater community resilience. Only 2% of all existing buildings in the U.S. are designated historic landmarks. But the remaining 98% also have important – if more humble – cultural significance. As markers of the everyday history of our built environments, we should carefully consider the preservation and revitalization of these structures, as well.

Poetical: “Architecture comes into being when a total environment is made visible…We have seen that this is done by means of buildings which gather the properties of the place and bring them close to man.” Christian Norberg-Schulz, 1979.6 Adaptive reuse offers enormous poetical possibilities to develop meaningful dialogues with time in the built environment. In this way, carefully revitalized buildings can viscerally connect us with the past, present, and future of each unique place, communicated through the experience of space, light, and materiality.

Urgency

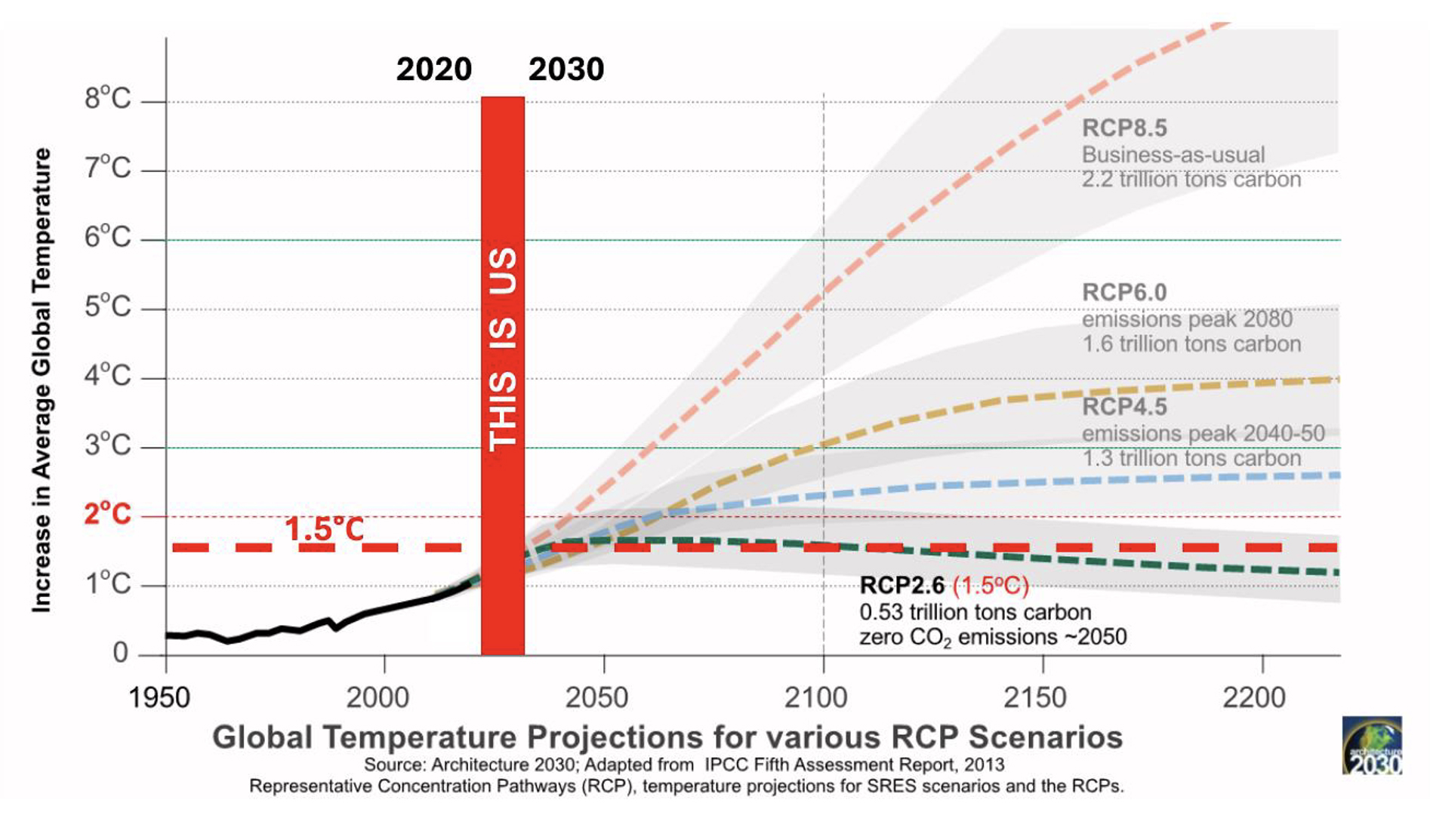

We must not squander the value of this giant embodied carbon bank, and we know that time is running out. 2023 was the hottest year since recording began in 1850. There is growing consensus among leading climate scientists that the goal of limiting global temperature rise to 1.5° C above preindustrial levels – approved by 196 nations in the 2015 U.N. Paris Agreement – is no longer achievable. Last month, the U.N. reported “the first 12-month period to exceed 1.5°C as an average was February 2023 – January 2024, when the average temperature worldwide was estimated to be 1.52°C higher than 1850–1900.”7 This month, in a survey of 380 prominent climate scientists who have participated in past U.N. Intergovernmental Panels on Climate Change (IPCC) reports, nearly 80% foresee at least 2.5°C of global heating, and 50% predict 3°C or more global heating within this century – levels that have been widely described as “catastrophic” to life on earth.8

Agency

We must act now to create a new architectural era of creative reuse, adaptation, and regeneration to help mitigate the worst impacts of the climate emergency. Architects at all scales of practice can be leaders in the rapid decarbonization of the built environment. Here are ways in which we can take meaningful agency on climate action in our work every day:

Champion Change: Embrace the reality of our rapidly changing planet as the greatest creative opportunity of our time. Change our design culture to reflect our own epoch, in which creative repair and regeneration have become a more intelligent option than wholesale replacement.

Evolve Practice: Adopt a “retrofit-first” policy in your own practice. Work to advance creative adaptive reuse as a practical, economical, and compelling alternative to ground-up construction. Learn to leverage the strengths and quirks of existing structures to optimize inspired design solutions.

Convince Clients: Ask your clients to consider adaptive reuse over demolishing and building new. Investigate and analyze the aesthetic, technical, cost, and schedule benefits for reuse, particularly of existing concrete and steel structures.

Dialogue with Time: Treasure what we already have. Explore a creative dialogue with time through the adaptation of existing structures. Preserve, evolve, and connect the cultural and physical history of our communities for future generations. This does not mean adherence to a static and artificial approach to strict historic preservation. Rather, it is a call to dignify, through contemporary design, the living evolution and continuity of existing places.

Shift Policy: Work to change public policy to prioritize retrofit of existing structures at local, regional, and national levels. Collaborate with municipalities and states to mandate deep-energy retrofits of existing buildings at key points in the real estate cycle – including property sale, renovations, and equipment replacement – through public policy and owner incentive programs. In 2023, AIA California successfully advocated for the adoption of key chapters of the International Existing Building Code (IEBC) within California’s Existing Building Code (CEBC). This change is expected to significantly reduce barriers to the adaptive reuse of non-historic existing commercial buildings to residential and other uses.

Change Codes: Promote zero-carbon building codes for new and existing buildings. When codes change, innovations in design thinking and construction technologies will be unleashed. Last year, AIA California and its partner organizations successfully passed the first state-wide embodied carbon building code in the nation. Starting on July 1, 2024, CalGreen will address embodied carbon emissions in construction, remodel, or adaptive reuse of commercial buildings larger than 100,000 sq. ft. and school projects over 50,000 sq. ft. These are important first steps, but the pace of change in our building codes must accelerate to have meaningful and timely impact on rapid decarbonization.

“The crisis is waiting, impatiently, for us to pay attention. To draw the line, the line that separates before and after. That was then, this is now; and now we act differently. We design and build differently. We imagine different futures.” Daniel A. Barber, 2024.9

Notes

1. As Architects’ Journal’s RetroFirst Campaign: Emily Booth, “Join Our RetroFirst Campaign to Make Retrofit the Default Choice,” Architects Journal, September 12, 2019.

2. The embodied carbon impact: Larry Strain, “10 Steps to Reducing Embodied Carbon,” American Institute of Architects, March 5, 2020.

3. 96 billion square feet: Commercial Buildings Energy Consumption Survey (CBECS), U.S. Energy Information Administration, September 2021.

4. 236 billion square feet: Brian Potter, “Every Building in America—an Analysis of the US Building Stock,” Construction Physics, November 2, 2020,.

5. U.S. architecture firm billings for adaptive reuse / renovation: AIA Guide to Building Reuse for Climate Action, April 5, 2024.

6. Christian Norberg-Schulz, Genius Loci – Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture, p. 23, Rizzoli, 1979

7. First twelve month period to exceed 1.5° C global average: UN Climate Action Fact Sheet, “1.5° C: what it means and why it matters”, April 2024.

8. Survey of 380 climate scientists: The Guardian, “World’s top climate scientists expect global heating to blast past 1.5C target,” May 8, 2024.

9. The crisis is waiting: “Drawing the Line: Architecture in the Anthropocene,” Daniel A. Barber, Places Journal, January 2024.

From arcCA DIGEST Season 17, “Adaptive Reuse.”