“The lyrical play between nectar and NutraSweet, between birdsong and Beastie Boys, between the springtime flood surge and the drip of tap water, between the mossy heaths and the hot asphaltic surfaces, between the controlled spaces and vast wild reserves, and between all matters and events that occur in local and highly situated moments, is precisely the ever-diversifying source of human enrichment and creativity.”— James Corner, in The Landscape Urbanism Reader (NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 2008)

“This emergent discipline (landscape urbanism) is not primarily about a sort of landscape gestalt—making cities look like landscape—but rather entails a shift in emphasis from the figure-ground composition of urban fabric towards conceiving urban surface as a generative field that facilitates and organizes dynamic relations between the conditions it hosts.”— Michael Hesel in Landscape Urbanism: A Manual for the Machinic Landscape (London: Architectural Association, 2003)

Landscape is becoming recognized as a powerful medium through which to address the larger environmental, social, and economic issues of our time. Increasingly, biotic systems, ecologies, watersheds, and open space are considered to be as important to the urban environment as infrastructure and built form. The very definition of landscape, popularly associated with the decorative or pictorial, is expanding to include the natural and the artificial, the lawn, the building, the city, the Sequoia grove. Field and void are becoming valued not merely as the residue of city-making, but as the medium of city-making.

Those working in the landscape medium are entering a time of “enlightenment,” brought about by the convergence of several key factors. Designers now have unprecedented access to primary data and web-based mapping sources, and we have the tools and collaborative potential to analyze, model, and represent the complex information available. Globally, a potentially lasting environmental consciousness, born in part of an awareness of resource scarcity, is compelling governments and communities to demand solutions capable of addressing the shifting dynamics of today’s network cities.Yet, no individual environmental discipline—architecture, landscape architecture, urban design, geography, or planning—has proven effective at realizing the landscape’s potential. Clearly, the expanded definition of landscape is too complex for any single discipline. We need a new synthetic practice that can address the complexities of contemporary urban dynamics.

California is the most geographically diverse state in the U.S., with some of the most extreme conflations of urbanism and ecology. Populations are rapidly increasing in coastal cities in earthquake zones where fire cycles determine the dominant ecologies. Within many of these cities, the landscape has become the locus of environmental and social debates. Recent public funding of open space bonds—such as Proposition 84, “Clean Water, Parks and Coastal Protection Initiative”—and large-scale public commissions offer great potential. Support for these bonds proves that open space has become a priority, along with concerns ranging from the need for recreation and walkable/ bikeable cities to regional water planning to the reparation of regional ecologies.

In California today, few open space projects are realized on greenfield sites; the emphasis is shifting to the infrastructural, the marginal, and the contaminated. Projects are more frequently within the post-industrial arena of military base closures, rail yards, brownfields, mining areas, transportation infrastructure, and landfills, which are in ample supply. These sites require a unique set of analytical skills, sensitive planning, and phasing strategies.

Today’s competition briefs offer an indication of the complex demands placed on those who design our urban landscapes. “Multiobjective” and “multi-benefit” have become buzzwords. A park is no longer just “a park”; it must be considered within the spatial context of flows and connections, access and adjacencies. It must be culturally and historically contextual and revelatory. It must address energy conservation, water quality, pollution control, microclimate, and social interaction, while providing habitat and functioning as a component of a regional ecological and urban identity. Projects must address myriad constituents, from soccer teams to birdwatchers, to survive public scrutiny. They must pay for themselves, with lifecycle costs carefully considered, and typically involve complex funding relationships: public/private partnerships, joint powers authorities (JPAs), and foundations. To meet these complex and often-contradictory demands requires a collaborative practice, in which multi-disciplinary teams analyze, synthesize, and ultimately design projects that may have unknown outcomes and forms.

Landscape Urbanism has emerged as the most promising discourse for integrating regional landscape planning and urban design, science and art, form and process. It combines knowledge and techniques from such disciplines as environmental engineering, urban strategy, landscape ecology, geography, and architecture into a practice that is both anticipatory and adaptive.

Landscape Urbanism refocuses landscape architecture’s fundamentals: temporality, scale, ecology, infrastructure, and environmental ethos. It bridges the divisive dichotomies that plague the environmental disciplines—artificial/natural, inside/outside, form/function, human/animal, void/mass—by operating within the spaces between them. Going against top-down, determinist models of design and planning, it investigates the indeterminate and the spatio-temporal. Rather than end-state solutions, it formulates scenarios that can adapt to change and unforeseen forces. This nascent discourse is committed to the generation of “operant” spatiality—the result of a commitment to habitat, biodiversity, infrastructure, water quality, in-situ reclamation, sustainable urban development, and energy generation.Throughout, ecological principles such as succession, normally applied to environmental systems, are applied to political, cultural, economic, and social systems. All are considered vital parts of the urban ecosystem.

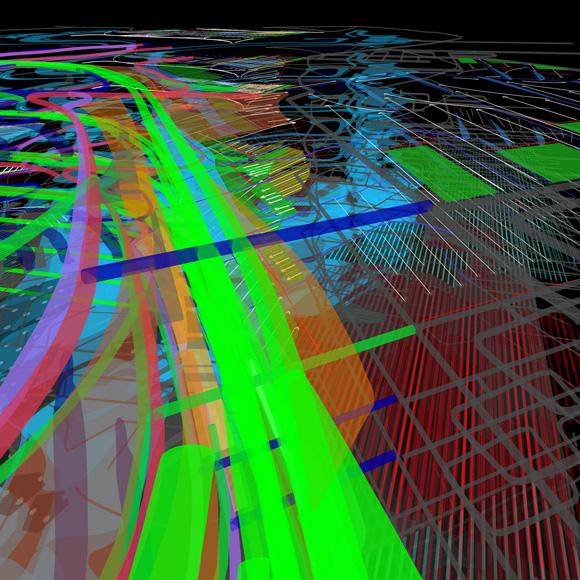

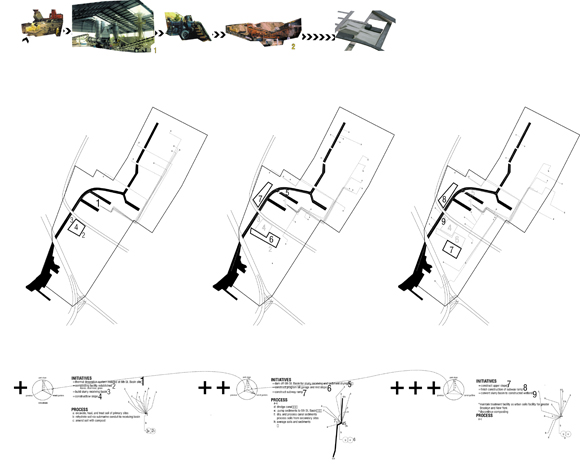

The discourse was first introduced in California at the “Representing the Designed Landscape” conference at UC Berkeley in November 2000, where James Corner, of Field Operations, presented their entry for Downsview Park, a new public park on a decommissioned Air Force base in Toronto. Corner focused on new modes of analysis and representation, highlighting the use of layered mapping and diagrammatic analyses expressing the relationships among programs, ecologies, and development. He showed phased plans and montages of incremental site evolutions, generating adaptive solutions that play out over time. Firmly rooted in the legacy of Ian McHarg’s mapping and overlay techniques, this approach has inspired a new generation of practitioners, educated throughout the world, most notably at the University of Pennsylvania, the AA in London, and the University of Toronto.

It is clear that Landscape Urbanism is the most compelling contemporary model for practice. What is less clear is whether the body politic is prepared to accept the indeterminate and incremental. Public desires are more rooted in the 19th century picturesque than in the processes and “messy aesthetics” of habitat, and politicians and bureaucrats often prefer the quick-win to the incremental or unpredictable.

As landscape architects on the LA River Revitalization Master Plan team, our team prepared time-based scenarios, focusing on the river’s potential as a transportation and wildlife corridor network in which infrastructure, both grey and green, is intertwined in new, symbiotic equilibria, and where the River transforms the City over time. Through over 24 public workshops and countless agency meetings, we found people to be receptive to time-based strategies and less interested in the restoration of the river to its pre-development, “pastoral” ideal. It became clear that community desires were remarkably well informed and supportive of innovative planning and design processes.

California could be a proving ground for an integrated, process-based practice. We must look more readily to the landscape, its systems and processes, as we reverse-engineer our cities to become more sustainable and ultimately more habitable. We are seeing significant shifts in the way we value the urban landscape, born of growing awareness of resource scarcity and the popular realization that a “park is more than just a park,” that our urban landscape is 99.9% time and must be planned to accommodate unforeseen outcomes and transformations. Landscape architects must lead the way, offering new narratives and using the tools that Landscape Urbanism has reestablished for projects of all scales—from the front yard to the urban greensward.

Author David Fletcher is principal of Terrain Landscape Architecture + Urban Design, a faculty member at the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc), and a Lecturer in the USC School of Architecture. He is presently a senior associate for the HOK Planning Group in San Francisco.

Originally published 2nd quarter 2008, in arcCA 08.2, “Landscape + Architecture.”