“Extend the sphere, and you take in a greater variety of parties and interests; you make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens; or if such a common motive exists, it will be more difficult for all who feel it to discover their own strength, and to act in unison with each other.”—James Madison, The Federalist No. 10

Design Mediation

Increasingly, architects, landscape architects, and urban designers find that the work they produce must mediate between development and public interests. This mediating role exists at every scale of development, from the back porch to infrastructure. This essay is the result of an interest I have in expanding the role of this mediating function of design work. I will discuss why and how the skill set at the core of our disciplines, coupled with information and communications technologies, might effectively mediate public dialogue on a contentious development subject. In this case, the subject is the California Delta, a place that is making the news on a more and more frequent basis.

How, or why, is any of this a problem for architecture and its associated disciplines? Our obligation to serve in the public interest gives our professions the authority of an objective platform vis-à-vis the various interests at play. In the context of any design problem, the drawings we produce are produced only after careful synthesis of the dynamic and often contentious interaction of cultural, political, economic, and aesthetic interests. Employing this analytic and representational skill set on a contentious landscape like the Delta, we can envision thoughtful and compelling design proposals at the scales of building, landscape, and infrastructure. These proposals can more fully embed the Delta’s distinctive uses, artifacts and places, historical events, and social practices in an exploration of the future of a changing public and private space.

What I will describe here is how design can reconsider infrastructures proposed through conventional planning processes, and how these infrastructures might become the sites of more complex and varied uses that embody the interests of diverse, often marginalized communities. Moreover, information and communications technologies have made it possible to engage networks of collaborators, interests, and communities tied together not only by geography but also by aspiration. I will describe a web-based forum and evolving archive that might expand community participation in discussions about the Delta’s future.

A Vital Organ

Undoubtedly, the Delta’s future will be characterized by change. As the source of more than half of the state’s fresh water supply, the Delta is vitally important to the state’s economy, and as the state’s population continues to grow, its access to water supplies shrinks. Consequently, a phalanx of community representatives, lawyers, hydrologists, environmental scientists, and civil engineers are studying how to increase the amount of fresh water supplied from the Delta. This is to be done by developing Delta water management infrastructure and, simultaneously, by restoring large portions of its nearly destroyed estuary ecosystem. This strategic marriage of the respective advocates of infrastructure and habitat development has produced a politically powerful coalition.

The agenda of this coalition was reflected most recently in Delta Vision: Our Vision for the California Delta, developed by a Blue Ribbon Panel appointed by Governor Schwarzenegger. Following a list of anodyne goals, the report is explicit in its description of the means to achieve them: state acquisition of easements across private property, improvements to and construction of levees, improvements to water conveyance and storage systems, and ecosystem revitalization projects—flood control, water delivery, and environmental infrastructures. It is less important to ask whether this report is the product of a sufficiently democratic planning process than to ask whether the quality of the landscape and place imagined in such a vision could be improved through the synthetic, mediating skills of design.

Communities, Interests, Internet

If one is to work at a scale as large as the Delta, one needs new ways to engage with the Client. The Delta is a complicated place, with communities and interests that overlap, contradict, complement, and contend with each other. This makes it important to distinguish between what a “community” is and what an “interest” is. The word “community” is often used to describe a collection of people who are tied together by the neighborhoods, towns, and regions in which they live. But communities may also form around shared identities, outlooks, ethics, or other commonly held principles that are not based in self-interest or on geographic proximity.

The great potential of a website is that it might link people who live in far-flung places but who share the same goals and principles. The political influence of a now mature environmental movement is an example of the potential of a community that formed around shared principles, not shared location. But while their historical achievement is certainly an important one, today’s Delta environmental advocates operate in a narrow world of technocratic negotiation. They could use a complementary voice and vision from outside.

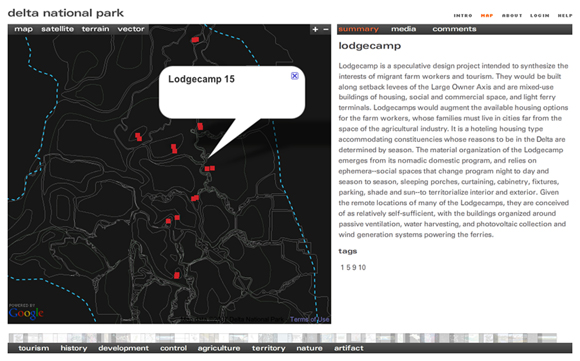

The Delta National Park website can be thought of as a public meeting place in which communities and interests can engage our disciplines. The website operates on three levels; first, it provides information about the Delta through a series of links, images, diagrams, maps, and other forms of description and analysis; second, it contains a series of design proposals at the scales of sub-region, town and settlement, and building; third, it gives registered users the ability to interact with this content in the fashion of Google Earth’s “Community” layer by uploading and situating comments and ideas, images and designs.

Case Studies: Shimasaki Memorial and Lodgecamp

The analysis and design work that I’ve done to date extends across scales from the region to the building. I’ve decided to focus on two building-scale examples in this essay. The Shimasaki Memorial and the Lodgecamp projects present different examples of how and what design might bring together in a broader coalition of interests and communities.

In order to galvanize a far-flung Delta community, one might create a space where the principle of recording ethnic history and the goal of historic preservation might come together. On Bacon Island, which is part of a private proposal for a water development project, there is a farm camp significant in the history of Japanese-Americans. The farm camp was the home of potato farmer George Shima, who in the early 20th century became the first Japanese-American millionaire. In the 2005 draft environmental impact statement prepared for the developers of the project, consultants acknowledged the camp’s significance and recommended that a “PBS-quality” video documentary be prepared as the method of preserving it. Considerable sums of money will be spent to reinforce the island’s levees and construct large pumping stations, but it is unlikely that any money will be spent to physically preserve any portion of the camp.

My proposal for the Shimasaki Memorial expands the program for one of these pumping stations. The proposal preserves a single building from the farm camp and adds a boat landing, an archive of Japanese-American agricultural history in California, and a bathhouse. This proposal illustrates an alternative to the banal design implications of the ongoing technocratic planning processes by affirming that the Delta’s future is not only as a fresh water supply but also as part of an expanding urban network of diverse uses and spaces.

The second case study addresses need rather than desire. It is also an opportunity to explore how time, migration, and exchange might be brought together in a new community of people and a rotational housing type to house them. The shortage of decent migrant and non-migrant farm worker housing is well documented. In 1995, James Gordon and other researchers at the UC Center for Cooperatives estimated that in California alone there was a shortfall of housing for 250,000 farm workers. Migrant farm workers, who by law and logic can only reside in the same location for 180 days, would share their housing with hunters who come to the Delta to hunt waterfowl, and bird watchers who come to watch those same birds, and a more general class of tourist who comes to the Delta to bike, fish, and otherwise recreate.

Sitting at the transition between the agricultural fields and the levee crest, the Lodgecamp is a dense, low-rise, high-density housing type that contains twenty-four housing units in a one-acre area. The units are lifted off the ground, and the ground plane is occupied by parking and an outdoor work area or shaded patio, depending on the user. A kitchen and eating area is suspended below the living and bedroom areas, which, divided by screens and curtains, are contained within an egg crate-like, plywood stressed-skin structure. Directly above the road on the levee crest is a multi-use space that might house distance learning facilities, a day care center, and a walk-in medical clinic at certain times of year, but becomes an Internet café, deli, and social club at others.

National Park or Geopark?

The premise of the Delta National Park is that change is inevitable there, and design can be an effective means to explore the trading of private and public commodities and interests. Similar to the transfer of development rights regulations that exist in both rural and urban contexts, these trading processes could be effective tools for building broader coalitions and making design proposals that are more complex than simply infrastructure or habitat. And while the project is rhetorically called a “national” park, it is in fact more like a geopark, a distinct place under tremendous pressure to change. (Fifty-six National Geoparks in seventeen nations are currently members of the Global Network of National Geoparks assisted by UNESCO, which describes them as areas “with a geological heritage of significance, with a coherent and strong management structure, and where a sustainable economic development strategy is in place.”)

At the scale of the geo-park, I have identified four “exchange authorities.” These are Delta sub-regions that are under specific threat and have unique opportunities to develop trading mechanisms between the various stakeholders whose interests are present there. Their extents are defined by particular geophysical situations, development pressures, and infrastructure needs. The Shimasaki Memorial and the Lodgecamp are located along what I have called “The Large Owner Axis” (see figs. 1 and 5), which is one of the exchange authorities.

The Large Owner Axis traces a north-south line between the two most important existing water-based infrastructures in the Delta, the Delta Cross Channel in the north and the State and Federal Water Projects in the south. It is part of the “Through-Delta Conveyance” option, once considered the preferred alternative for achieving increases in water supply. Recently, however, another water conveyance proposal has emerged to rival the through-Delta proposal. This new proposal would be constructed along the quickly urbanizing I-5 edge of the Delta. Called by the Public Policy Institute of California “Peripheral Canal Plus” in their recently published Envisioning Futures for the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta—the most up-to-date, comprehensive, and readable independent assessment of the scientific, physical, economic and political situation in the Delta—this new (or not so new) alternative runs through the Borrow Pit Exchange Authority (see fig. 5). Although I have done some preliminary mapping of the I-5 edge of the Delta, studying its suburban morphologies, infrastructures, and land uses, the new peripheral canal proposal opens up interesting design territory.

It is not in the best interest of Californians to accept a future Delta landscape that is little more than water and environmental infrastructure. The rapidly urbanizing Delta perimeter will only increase the numbers of people who already look to the Delta to provide various types of recreational diversion. And it is already evident that developers will continue to make planned development proposal forays deep into the below-sea-level polders of the Delta, creating suburban landscapes only vaguely informed by the Delta’s specific geographic qualities.

The Delta website is intended to be a public meeting place where people with varied knowledge, skills, and concerns come to share ideas and opinions about the past, present, and future of this place. A web-based multidisciplinary project that situates alternative proposals for the Delta’s future might be able to do what James Madison was getting at when he proposed to “extend the sphere” beyond the interests of the majority. The Delta National Park website has a spatial and scalable component, and it is not only interactive but collaborative as well. The Delta is too big for an individual to handle alone, and what I’ve produced simply establishes a context for the work of others. The site is now operational at www.deltanationalpark.org, and its public function has begun. Registered users are able to upload comments and contributions, and I look forward to fielding questions and providing direction on possible projects to anyone who wishes to join in producing content for the site.

Author John Bass is an Assistant Professor in the School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture at the University of British Columbia. His research explores contested landscapes, including the California Delta and the coast of British Columbia.

Originally published 2nd quarter 2008, in arcCA 08.2, “Landscape + Architecture.”