On sparsely inhabited Santa Cruz Island off the Southern California coast, there exists a 1900s rancho complete with vineyard, ranch house, and a small, simple chapel. Once a year, a group arrives on the island to celebrate the Feast of the Holy Cross—the island’s namesake. Worshippers arrive on boats and small planes and walk from the shore or dirt landing strip in quiet excitement. In front of the small chapel, a guitarist, singer, altar boy, and priest lead the procession inside. Not all visitors can fit. Some sit on the surrounding hill. Mass is celebrated with singing and music. After the celebration, a procession leads to the ranch house for a fiesta, which culminates this very special day. It is a simple, yet profoundly spiritual, experience.

The worshippers’ spiritual journey begins the moment they decide to participate in the annual ritual—when their mind first anticipates the experience of spiritual reflection and renewal. The preparation, physical journey, and layering of rituals add to the experience of moving away from the everyday world into a spiritual realm. This sacred journey, incorporating elements of ritual, procession, surprise, and transformation, is central to the design of spiritual spaces.

The Spiritual Journey

Recently, I was speaking with a film-director friend about the narrative nature of architecture. “It’s like creating a film,” he said. “You don’t want to reveal the plot at the beginning. Instead, you want to reveal the story slowly, building up to the climax and conclusion, and leaving your audience with a message.” Like the creation of a film, the successful creation of a space that transcends the everyday depends on t his narrative build-up.

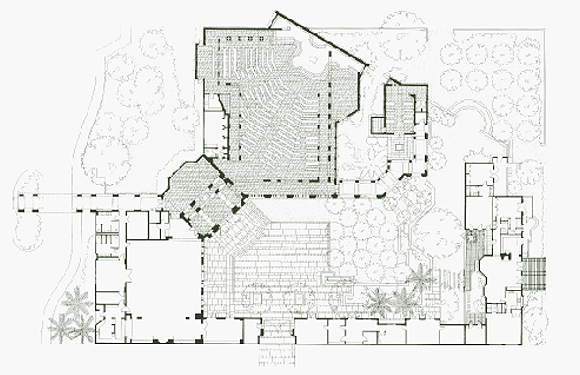

The spiritual journey pertains to all building scales and religious traditions. It is just as relevant for a cathedral, a mosque, a synagogue, or a simple suburban church. A great example of the journey is the Church of the Nativity in Rancho Santa Fe, designed by Moore Ruble Yudell. From the thick front gate, through the landscaped gathering space, into the worship space, the transformative journey is exquisitely choreographed using space, form, detail, and material.

In too many other instances, designers overlook the importance of the transformative journey. Often, the architecture gets simplified into a question of site planning. First, locate the parking lot, then place the vernacular form of the church, mosque, or synagogue. It is as if the designers expect that the space will evoke a spiritual response simply because it is labeled “church,” or crowned with a steeple.

The architect must strive to accomplish more. Trained to design spaces that evoke emotional response, the architect must draw upon the tools of design to create spaces that speak without words. Spaces that, through their spatial vocabulary, can evoke emotions that ennoble the human spirit and provide the proper physical and symbolic setting for worship and reflection. The architect must use these elements to choreograph the sublime experience and bring the worshipper into the spiritual realm.

Sense of Place

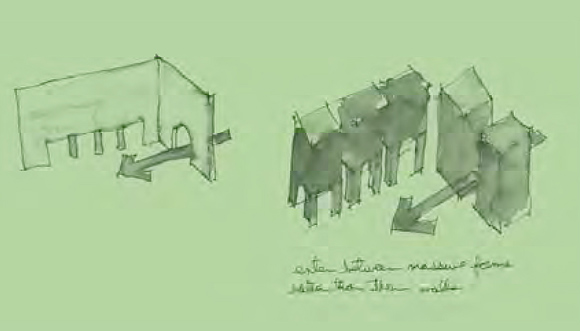

In designing the Church of Our Lady Queen of Angels in Newport Beach, we were confronted with a suburban community filled with new, quickly constructed structures that are mostly lacking a sense of permanence. We designed the church with thick walls punched with holes for doors and windows and partition walls that act like heavy slabs, forcing visitors to move around them in order to enter the worship space. The solidity of the form adds import and awe, identifying the church as a permanent entity within the community. The spiritual journey continues as the worshipper begins the procession toward the sanctuary. That procession elevates the individual’s mental and emotional state, engaging both the senses and spirit.

In designing this path, the architect must still answer the somewhat banal questions of parking, capacity, and egress. But the poetic essence of the procession is attained by choosing materials, colors, textures, sounds, smells, and light effects that reach the soul and initiate its sublime transformation. In the recently completed Our Lady of the Angels Cathedral in downtown Los Angeles, Raphael Moneo extends this procession to dramatic effect, elongating the ambulatory to emphasize the worshiper’s journey.

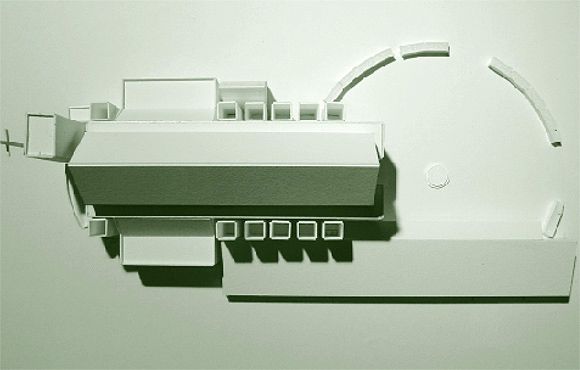

In the suburban context of the Padre Serra Parish Church in Camarillo, California, we orchestrated the procession to begin while still in the car—passing through the specially designed decorative gates. The journey continues as visitors enter on foot into the lushly landscaped plaza, filled with native plants that evoke a Southern California version of the Garden of Eden. The landscaping becomes more lush and the church’s color palette more vibrant as worshipers move through the courtyard and into the sanctuary. In the soon-to-be- completed All Faith’s Chapel at Chapman University in Orange, California, we employ a dramatic use of natural elements to define the procession space. Because of the inclusive mission of this chapel, the design equates nature with the spiritual in lieu of religious symbols.

Within the transformative journey, the architect must create spaces that encourage and celebrate the communal aspect of religious worship. A communal space can be as simple as the landscaped courtyard at the Padre Serra Church, which encourages congregants to share the experience of moving into the spiritual world together. Or, the communal space can be an integral part of the worship space itself. When the Vatican II liturgy recognized the importance of the shared experience of worship in the Catholic faith, it encouraged the movement of the altar to the center of the worship space (a change that we first incorporated into the plan of the Padre Serra Church). In the All Faith’s Chapel, the multi-denominational aspect of the space necessitated a flexible layout, but also one that would allow several religious communities to come together. To create that flexibility, we designed a main worship space as well as a small reservation chapel for individual worship.

Lighting the Way

Since the earliest construction of churches, the manipulation of light has been a prime concern of religious architecture, its effects often being as important as the physical forms it illuminates. Light and enlightenment are the most persistent of sacred and religious metaphors. The potential of modulating light and space can be one of the architect’s most powerful tools in evoking reverence, love, and awe, while at the same time creating the appropriate drama and focus, as well as the variegated textures so important in religious spaces. Le Corbusier, in describing his chapel of Notre-Dame-du-Haut at Ronchamp, said, “The key is light, light illuminates shapes and shapes have an emotional power.”

Daylight should be specifically designed and directed with the precision and attention to detail often reserved for artificial light. At Eero Saarinen’s Chapel at MIT, the sense of mystery comes from the dramatic, yet simple, lighting effect. In the Chapman Chapel, we took great pains to create a balance between the desire for a bright, light-filled, and airy feeling, and the need to create an awe-inspiring effect. Too much natural light would neutralize the effect of the multi-colored, punched-out windows. The solution was to work with artist Nori Sato to create side windows that use light as an artistic material. Even the ambient light in the small chapel is specifically designed to filter through translucent panels, so that the wall appears to glow.

There is a long tradition of the integration of art into sacred spaces, but, in the middle part of the 20th century, that tradition began to be stripped away. Modernism separated the artists from the institutions of religion. Art is now becoming reinvested into these spaces. The artistic vision not only moves a space beyond the realm of the everyday, but also elevates its ability to stir the soul. Art activates the surfaces and forms, creating possibilities for storytelling and symbolism as well as visual poetry. For centuries, religious facilities have been among the world’s greatest patrons of the arts. If art is the pathway to liturgy and through art we become more in touch with God, than art must indeed be an inseparable part of the architecture of the church.

Sacred spaces—whether of religious, artistic, or natural circumstances—are places that touch our soul. The architect has both the responsibility and the creative opportunity to infuse these spaces with a sense of joy, reverence, and reflection and to create a journey that transcends the everyday world.

Author David C. Martin, FAIA, is design principal of Los Angeles-based AC Martin Partners, an integrated architecture, engineering, and planning firm. Founded in 1906 by Albert C. Martin, Sr., the firm continues to shape the Southern California region, creating user-focused, innovative, sustainable, and beautiful landmarks for the 21s t century. David Martin wishes to thank Elizabeth Meyer for her assistance on this article.

Originally published 4th quarter 2003, in arcCA 03.4, “Reflect Renew.”