You hear a lot these days in planning circles about “transit oriented development,” “smart growth,” “transit villages,” “new urbanism.” They all mean denser development near transit, filling in the city so the suburbs don’t sprawl. “Mixed use” comes up a lot—living over stores, walking to run your errands. The other hot topic is “public/private partnerships,” governments and private developers getting together to develop a public benefit use, leveraging public funds or land with the entrepreneurship and risk-taking of a private developer. Pretty much everyone gets behind the ideas of mixed-use infill development near transit and of public/private partnerships. Here is a case study of what can happen when such a project is actually attempted—at least in one case, in one neighborhood, with one developer.

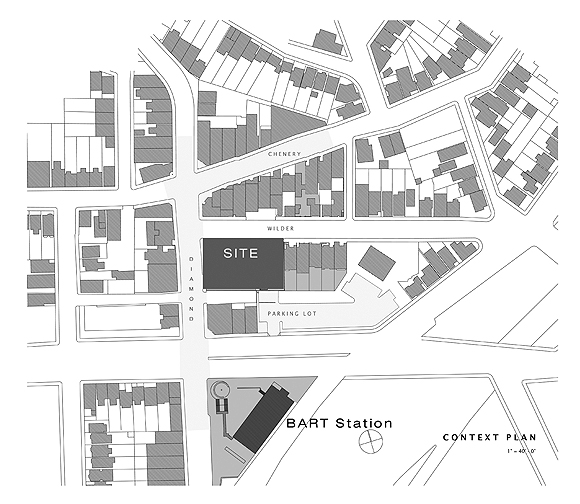

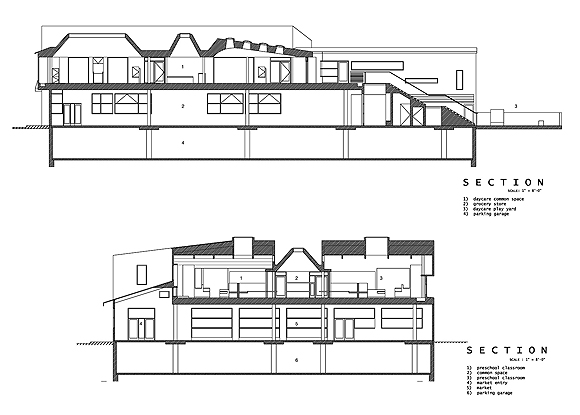

The project is a family-owned, neighborhood-serving grocery store, a new branch library (replacing a tiny leased storefront branch a block away), and fifteen two-bedroom apartments, two of them low income and subsidized by the development. The 16,000 square foot site is a block from a BART station and within a few blocks of five bus lines. It is in Glen Park, the kind of San Francisco neighborhood where the old-timers couldn’t buy their homes today. Most homes are one or two stories over a garage, with some newer developments of up to four stories.

Until a fire in late 1998, the site held the Diamond Super and its popular butcher. The rear two-thirds of the lot contains about 25 metered parking spaces, open to the public, on a month to month lease with the City. The previous owner had entered into this arrangement, because non-customers were using up his lot, and he didn’t want to police it.

After the fire, neighbors deluged the listing realtor with petitions—2,500 signatures—with one message: no chain store. And, in fact, Walgreen’s was keen on the site. In response, the Mayor and Board of Supervisors issued resolutions calling for the return of a neighborhood-serving grocery.

A neighborhood couple formed the Glen Park Marketplace Phoenix LLC to accomplish that goal by purchasing, in cash, the several lots on which the project will be built. The original proposal was to build a full service grocery store with a childcare center on the second floor and in the back, and with a floor of underground parking for store patrons. Right off the bat, this project was unique. The motivations were to provide a grocery store and a childcare center, not to make money. The times were different, and the owner was flush.

The Team

I was the fee developer, meaning that I was paid to assemble the site, develop the program, negotiate the sales of the building spaces, secure entitlements, find financing and insurance, contract with and manage consultants, etc. I put no money into the deal and shared neither profits nor losses.

I had served as the Mayor’s Project Manager for the 300 acre Mission Bay Redevelopment project and Pacific Bell Ballpark, experiences that were of limited use in the development of a grocery store. But the vocabulary and broad categories of tasks—site assembly, real estate transactions, environmental review and entitlement, financing and design were remarkably similar. I had also served on the Planning Commission for four years, which was quite a bit more useful, primarily for giving me insights into what decision makers are looking for in projects and submittals.

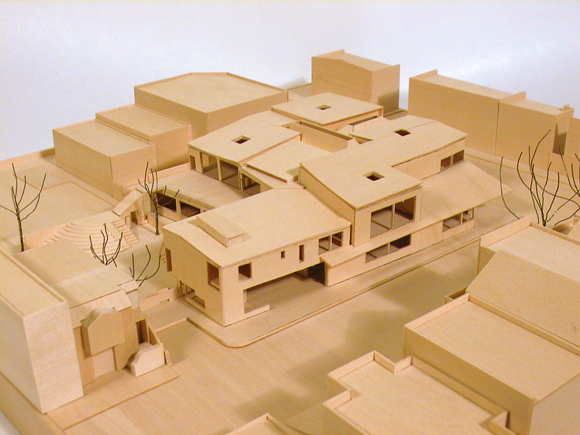

Peterson Architects was chosen to design the project after winning an invited competition among four firms. We liked their design point of view and commitment to making a good pedestrian experience. We also retained a general contractor early in the process.

The owner/investor, the developer, the architect, and the contractor were all San Francisco residents. To give an idea of how atypical this is, I never met anyone working for Catellus, the Mission Bay developer, who lives in the City.

Evolution

I inherited the program of grocery store, childcare, and underground parking. But the program changed pretty fast.

When we bought from the City the adjacent parcel, the Planning Director ordered that we provide the maximum number of housing units and the minimum amount of parking. Two of the housing units are to be affordable to low-income families, subsidized by the developer, under an exaction formula passed by the Board of Supervisors midstream. The formula calls for 10% of the units to be “affordable,” and at fifteen units we had to round up.

Finding a grocer was more difficult than we had anticipated. As often happens, the grocer we selected, Sam Mogannam, came to our attention from a mutual friend he met at a dinner party. Sam and his brother Raphael grew up in the grocery business, having taken over the Bi-Rite grocery begun by their father and uncle at 18th Street between Guerrero and Dolores Streets. It’s the kind of grocery with flowers out front, a deli counter, organic produce, pastries baked by the owner’s wife, and a wide selection of affordable wines.

The project has a third component: a new branch library. In November 2000, voters passed Proposition A, a $106 million bond issue to finance the rehabilitation or replacement of inadequate branch libraries, with Glen Park’s tiny 1,500 square foot branch at the top of the list. I suspected that dealing with the City bureaucracy would add a new level of complexity and brain damage to the process. But we felt that the inclusion of a library added panache to the project as well—and besides, my mother had been a librarian. After a lengthy community review process, the Library Commission in July 2002 approved recommending that the Board of Supervisors authorize the purchase of approximately 9,200 square feet in the project.

Negotiations with the library were long and difficult. One architect works for the Department of Public Works while another is a consultant, the City Real Estate Department has responsibility for the business transaction, the City Attorney’s office sat at the table as the City’s lawyer. Fortunately, the City Librarian, Susan Hildreth, herself took the lead with the Library Commission, community, and Board of Supervisors. Without her, we would have been stuck.

Most of the negotiating was about the extent of upgrades we would build for the library. In retrospect, we and the City both erred in not more clearly defining the elements we were selling the City. Allocation of costs and responsibility for design and financing of such items as heating/ventilation/air conditioning systems, fire sprinklers, bike racks, and even window cranks were hashed over endlessly. Typical of the difficulty of the negotiation was the City’s requirement that we purchase earthquake insurance during the construction period. This insurance is very expensive and has such a high deductible that no private developer would bother with it. The structure of our arrangement with the City was that we build them a shell and then turn over the key, financing the construction and running the risks of overruns, delays, or earthquakes. But the City’s Risk Manager was used to public works projects where the city contracts a builder to deliver a product and pays as it is built, triggering a raft of bidding, diversity, foreign policy, and wage burdens along with insurance requirements. The City agreed to a compromise: we would get earthquake insurance only if it were available at a commercially reasonable rate. But the City refused even to discuss a definition of commercially reasonable. The City wanted the benefits of a private developer taking the risk and fronting the money, while otherwise treating the project like a typical public works project.

From a grocery store with a childcare center and a story of underground parking, the project evolved to a grocery store with a library and housing above. While this made for a more interesting project and one with some hope of financial feasibility, the groundwork we had done to introduce the earlier proposal came back to haunt us. There was a sense of betrayal among some of the neighbors (and more particularly the merchants) over the loss of the previously proposed parking. When I explained at a merchants meeting the infeasibility of the underground parking, a shopkeeper said that feasibility was our problem, not theirs.

Entitlements, Opposition, and Support

So we felt we had a pretty good project and team. The project was designed to meet the community’s needs for a grocery (as evidenced by the petitions and resolutions), housing (responding to the Planning Department’s mandate), and a library (as evidenced by the passage of the library bond and the Library Commission’s action to buy from us). In fact, when a committee representing the Glen Park Association and Glen Park Merchants Association presented us with a document outlining their vision for the site, we responded by asking to recast it as a joint statement and signed on.

Now we needed environmental review, three conditional use permits (for a non-residential use above the first floor, a store larger than 4000 square feet, and any development of a lot larger than 10,000 square feet), and four variances, including one releasing us from the obligation to provide 14 parking spaces for the store and library. (All of the variances and one of the three conditional uses were triggered by the library.)

We applied for the planning approvals in February 2002, and shortly after that the Planning Commission shut down because of an impasse between the Mayor and the Board of Supervisors on appointments. We frantically tried to get a hearing date before the Commission shut down on July 1. Instead, we fell into a five-month delay. During those five months, both opposition and support for the project grew.

By far the biggest issue was parking. We had underestimated the passion for the parking lot that the project would displace. The merchants wanted a lot for themselves—one of the project opponents wrote that, “an informal poll indicates that, at any given time, as many as fifteen to twenty spaces in the village are taken up, not by shoppers or residents, but by the employees of local businesses,” and the Glen Park News reported that, “already, merchants set timers so they can remember to move their cars every two hours.”

The Planning Department’s environmental review staff required a traffic study. We had to hire (at about $50,000) traffic planners to apply the Department’s methodology to assess likely parking demand. This methodology is based on suburban shopping habits and resulted in a finding that just about everyone going to the store or library would do so by car. The planners would not adjust the methodology to account for the existing library which would close, the five bus lines and regional BART station within a block, the City CarShare cars available to be borrowed in the lot next door, the home delivery planned by the store, or the neighborhood-serving nature of the uses proposed.

We learned that the Glen Park BART station is the only one in the system with unregulated on-street parking, so BART commuters drive in from the Peninsula or down from Diamond Heights, park on the street, and ride BART. According to the Planning Department, Downtown Glen Park has 183 spaces without meters or permit requirements. I brought the Director of the Department of Parking and Traffic out to meet with the Merchants Association and he agreed to a raft of measures proposed by the Glen Park Association and the Merchants. Meters, two-hour zones, and increased enforcement are being implemented. Did this help blunt opposition? Not in the least. In fact, they argued that increased parking turnover would decrease pedestrian safety.

The merchants believed that the vitality of the commercial district requires the parking lot. They didn’t see that, overall, the addition of new attractions to the downtown—a neighborhood-serving grocery and library—would increase foot traffic to their stores. Nor were they flexible enough to accept that parking solutions could be off-site. It became clear from the testimony and letters of supporters and opponents of the project that at root residents of Glen Park hold two different visions of the role of their neighborhood and its future. Two comments represent these divergent points of view:

“We moved to the area because of many things it offered but mostly because of the BART station and village proximity and what the village had in the way of shops. I don’t drive at all and do all my traveling on public transportation or by using my feet. The market that was in place before the fire was a large part of my daily schedule. It allowed me to get some fresh produce, small items and great stuff from the butcher shop without having to get a ride from a friend to a larger, characterless store. I grew up in Switzerland and London where this sort of way to shop, small amounts frequently, is much more commonplace.”

“You are driving out Americans in favor of urbanites with politically correct lifestyles.”

Some opponents resented my role as a former public official and thought that there must be some back room deals being made. This suspicion was echoed by the Bay Guardian in a piece entitled “Let Them Eat Books: Pro-development forces battle community interests over Glen Park branch library, condominium.” It says, “Making matters worse was the fact that the Glen Park Marketplace is represented by David Prowler, a high-powered lobbyist who served as planning commissioner and economic development director for Mayor Willie Brown. Such a prominent political connection fueled speculation by project opponents that they were shut out of the planning process.” This after fully thirty public meetings and hearings.

Some of the opponents objected to the height of the building, in part because project opponents posted doctored drawings of the project in storefront windows. At thirty feet in front and forty feet in the rear, the project height matches that of surrounding buildings. If the building looked like the doctored posters, I’d have opposed it myself.

From reading the Bay Guardian, one would conclude that “the community” hated the project. But how can you tell what “the community” wants? The Housing Action Coalition, the Executive Committee of the Glen Park Association, SPUR, the Bicycle Coalition, the Sierra Club, and scores of neighbors came to hearing after hearing to support the project. SPUR called it the “perfect project” and “a planner’s dream.” The San Francisco Chronicle said, “talk about a project with San Francisco written all over it.” When we had a booth at the Glen Park Festival, support and impatience for the project were almost unanimous.

Public hearings regarding different aspects of the project were held before the Public Utilities, Planning, Library, and Parking and Traffic Commissions. Each voted unanimously for the project. Opponents appealed to the Board of Supervisors, who also approved the project unanimously. Opponents then appealed to the Board of Permit Appeals, which held three separate hearings on the project, each about a month apart. The Vice President, Kathleen Harrington, not only voted against the project but also egged the opponents on to sue. (They did.) As she explained her vote in the San Francisco Examiner, she is “a pro-parking kind of gal.”

These hearings required a tremendous amount of outreach—signs posted on the site, letter-writing campaigns, even a storefront open house with models, attended by project opponents as well as supporters and catered by Bi-Rite. The City Librarian arranged meetings with all the members of the Board of Supervisors willing to meet, and she, representatives from the neighborhood, Sam from Bi-Rite, and I made the rounds. Opponents did the same. Bevan Dufty, the local supervisor, and I sat for a Saturday afternoon in front of the site with a sign saying, “Talk to Us About the Marketplace Project.” We had a booth at the Glen Park Festival and handed out 500 brochures, and I wrote update articles for each issue of the quarterly Glen Park News, delivered door-to-door to each household in the neighborhood. Nonetheless, at each hearing, without fail, we would hear testimony that the project was being slipped by the community without input or notice.

The opponents were real bulldogs. The day before the Supervisors hearing, I came to my office and found a swastika on the door. When I told a supervisor’s aide that I doubted it was connected to the project, she told me that, based on the calls they were getting, I shouldn’t kid myself.

We made it through the entitlement process and the appeals in April 2003—over a year after applying for permits— and I devoted my efforts to meeting with lenders, loan brokers, and insurance brokers. I must have interviewed a dozen of each. The lenders had a strong preference for residential condo units rather than rentals and some would not even consider loans on rentals. On the other hand, contractors, architects, and engineers are squeamish about condos because of the history of lawsuits. The project suffered a delay when our mechanical, electrical, and plumbing engineer walked off the job when we wouldn’t indemnify him for everything forever, whether his fault or not.

From a financing perspective, it’s pretty straightforward: you build a building with three elements, sell off the library and grocery portions, and then rent or sell off the housing units one by one. It was trickier to guess what sales prices or rents we could get at a point two years hence. I didn’t like to root for high housing prices, but that’s what it would take to get the thing to pencil out.

In any event, it was the drop in interest rates that kept the project alive. Our consultant, Marie Jones, performed constant financial analysis, and it was always a great pleasure to watch the feasibility look rosier and rosier as we got quoted lower rates. I was surprised by how dynamic the spreadsheets were—changing one assumption could make a really big difference in whether the project made any sense or not. And assumptions were always changing.

Stuck

By the spring of 2003, we were expecting a fall groundbreaking. The entitlements were in place, we had a grip on the insurance question, and construction financing at a great rate—4.45 with one point—had been found. We planned to break ground in October. Then the project hit three roadblocks.

The first blow was the decision by staff at the Planning Department, six months after the project was approved, that they didn’t like the design. We didn’t expect to get pages of comments six months after the Commission approval. According to the calls and memo we received from the department, no fewer than six planners had been discussing the design. We were asked to come in to discuss “just a few tweaks,” which turned out to include removing structural columns holding up the library or removing the outdoor seating at the store, making the building front “less horizontal” (it is thirty feet tall and a hundred feet wide), and making the “very crisp” façade “consistent with the existing neighborhood”—a hodgepodge of Victorians with apartments or offices above small storefronts. We could not see why a building with a grocery on the first floor and a civic use on the second should mimic neighbors of such differing use. Until the planners are all satisfied with the design, no site permit.

Then the owner, strapped for cash for another project, decided he had no choice but to sell the project. And until a new owner was found, cash outlays—all out of pocket—were to stop. No more engineering drawings, no lawyers to review the condo documents, no money to pay the architects to redesign to meet the Planning staff’s objections, no movement on financing.

What really made sale hard was the lawsuit. A group called “Glen Park Neighborhood Group of Concerned Citizens” filed a suit at the last minute against the City for having certified the adequacy of the environmental review on the project. (The Planning Commission, Board of Supervisors, and Board of Permit Appeals had all acted to uphold the environmental review—with the exception of the “pro-parking kind of gal,” unanimously.) The lawyer for the petitioners was a recent member of the Bar, the owner of the video store across the street. At the mandatory settlement hearing, I asked what they would consider an acceptable compromise, what would they like to see built on that site in the center of their community. They were flummoxed—they knew for sure what they didn’t want, but had no clue what would work for them.

For sale, sued, and without design sign-off, in late August the project was stalled.

Lessons

Here are some things I learned:

- First, a big mistake: we shouldn’t have gone public until the program was settled. It didn’t matter how often we described our project once we had submitted the plans, some neighbors felt that we had pulled a bait-and-switch when we took out the underground parking. We had never sought any statements of support for the previous proposal, we had never submitted any applications for it—it didn’t matter.

- We should have done more financial feasibility analysis right off the bat. But if the owner had done any such analysis, the project would not have happened, and it is likely that Walgreen’s would have bought the site.

- Not everyone likes the idea of mixed-use development near transit. Particularly in a predominantly single-family neighborhood, multi-family housing isn’t welcome, whether there are other uses in the building or not.

- Not everybody likes a public/private partnership, either. From the City’s point of view, it required more flexibility and trust than they are used to. From the public’s perception, the partnership seemed suspicious. The Bay Guardian editorialized that “it might set a precedent for more public/private partnerships and for more such suspect ways for private business to nibble away or steal outright a valuable public asset.” From a developer’s point of view, a partnership with the City requires patience, an understanding of complex decision-making dynamics, and the stomach for a very public process.

- Much of the fate of the project hinged on externalities. Some examples:

– During the course of planning the project, construction loan interest rates came down from 7.5% to 4.45%. Thanks to the drop in rates, the project will make money, though not the kind of return most investors would be satisfied with. At the same time, it is the drop in residential mortgage rates that has enabled housing prices to defy gravity to this point and remain buoyant despite job and population loss. If interest rates spike when the housing is completed, sales prices will of course drop.

– Nobody could have foreseen that the Planning Commission and Board of Permit Appeals would shut down for five months because of a dispute between the Mayor and the Board of Supervisors.

– The sale of the project and the hiatus on project spending were caused not by anything intrinsic to the project, but by the owner’s need for cash for another project. And this need for cash was a result of the crash of the stock market.

– Even the war in Iraq has had an impact. Due to increased military demand, the price of lumber has just about doubled.

- The vehemence of the opposition took us by surprise. They organized letter writing campaigns, public testimony, and lobbying. They wrote letters to the editor, posted posters in shop windows, called me names on the street (“neighborhood wrecker,” for example), and filed a lawsuit. They threw up objections based on the process, on suspected toxics, on pedestrian safety, parking, the process, zoning, traffic, height, loading, and the size of the store.

- And one thing I had learned in my years on the Planning Commission came back to me: you can’t solve psychological problems with land use decisions.

- I still ask myself whether the project team should have met more often with the opponents, or even involved a mediator like Community Boards. Should we have tried harder to explain why they couldn’t get what they wanted—a new library and grocery—without loss of the parking and the inclusion of housing? I doubt it would have helped, but it nags me.

- The size of the project was a real challenge—too big to slip under the radar, too small to absorb all the fixed costs of environmental review, legal fees, design, elevators, and time, which would be about the same for a project triple the size.

- It’s important to keep clear about the goals of the development and to revisit them from time to time. It may seem apparent that the goal is to make money and move on; the reality is more complex. The developer has to weigh speed, risk, complexity, quality, and the desire to create a neighborhood- enhancing legacy. In this case, all but the legacy goal would have justified dropping the library out of the program.

- I’ll take the blame for pushing the envelope of the design. I wanted a clean, modernist building, one with high-quality materials but which looks like what it is—a building built at the beginning of the 21st century to contain a grocery, library, and housing. I brought Peterson Architects loads of architecture books with yellow stickies showing buildings or parts of buildings I liked. I brought dozens of photos of new Dutch architecture. I should have paid more attention to what the neighbors, planners, and housing market want. When a city planner said that the building design looks like a factory in Holland, it was meant as a criticism.

- More surprising to me was what in some cases appeared to be the lackluster engagement of City staff. Response times were lengthy. Although the Planning staff and Commission were supportive of the goals of a library, market, and housing, the conceptual support often didn’t translate into any apparent interest in actually moving the project along. At the last minute, an anonymous Planner went to Supervisor Aaron Peskin, alleging that the Planning Department had somehow screwed up the review of the proposal, causing a three week delay in the library sale. I came to realize just how spoiled I had been when I worked in the Mayor’s Office managing the ballpark and Mission Bay. Big projects, with big developers and the Mayor’s personal engagement, got a great deal of departmental discipline.

Conclusion

The lawsuit has been dropped. In October, the project was sold to a loft developer who chose not to extend my contract. Peterson Architects are off the job. But the builder who bought the project hoped to break ground by May.

Author David Prowler was the City of San Francisco’s Project Manager for Pacific Bell Ballpark and Mission Bay. He is now a developer and development consultant. A version of this article appeared previously in the newsletter of the San Francisco Planning and Urban Research Association (SPUR).

Originally published 2nd quarter 2004 in arcCA 04.2, “Small Towns.”