David Erdman: In your and your peers’ work, I see a clear intention to render different systems but not let any one become isolated. Often, each is assigned a different materiality and geometry—one for an urban scale, another for the scale of the body. Those different “orders” are never allowed to totally gel. I think about your Sixth Street House and how you were drawing in earlier projects, where the edges are blurry due to a layering of different scales. This layering seems to be a meditation on boundaries and space, on inducing fullness by making those orders less legible. I suspect our generations share this intention, but in different ways.

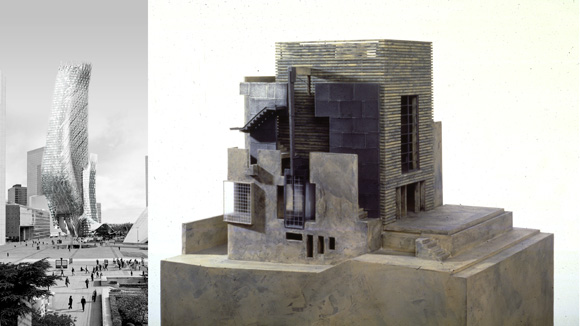

Thom Mayne: But with Sixth Street, I was attacking the singularity of the thing, and it led immediately to an idea that the elevations were radically different and dealt with the contingency of a particular place. It was connected to an urban idea, a potential for radical difference of things.

Erdman: There seems to be an assumption that working with effects is an effort to reduce multiplicity and limit design to singularities. I can’t say with certainty what the specific effect of a project will be, but I can make sure I’m working with a number of different orders and qualities. The similarity between us is that there’s an intentional murkiness between these orders; the difference may be that they’re more pushed together in our generation than they were in yours, perhaps because of ways of modeling and drawing.

Mayne: It seems, with your work, that the method itself is a connective tissue. Whether it’s Maya or whatever tool you’re using, it changes the equation. That has had a huge effect on your generation. There’s the smoothing or the connectivity that comes out of the computational mathematics.

Erdman: Initially, yes, but it’s evolved. The more recent obsessions with effect, mood, and atmosphere require different materialities—not necessarily literal materials but often more abstract formations. For example, I’m only interested in “interaction technologies” or “luminosity” because they provide other dimensional ecologies that work on the material stuff I’m organizing in the space. Immaterial and material play off one another, and because they can’t be coordinated within the same software or the same dimensions—some operating in four or more—they are difficult to organize exclusively using Maya. You have to look at them in many ways, often prototyping at full scale.

When Greg [Lynn] and Sylvia [Lavin] and Neil [Denari] brought us out here to teach, many of us focused on these almost rote, “demonstration” projects—often installations. They offered a way to get our hands on technologies that a small practice mightn’t otherwise acquire; and they provided a theoretical territory in which to explore the design implications of LA’s technological assets. Did your early development among colleagues in LA have a similar progression?

Mayne: When we did that it was very small projects, but somehow they were immediately affected by material and tectonics and their role. But it was quite conventional, almost nineteenth-century. I was looking at Diderot. There was definitely a commonality at a mechanical, material, tectonic level among the people here. It was challenging the simplicity and the crudeness of the construction that takes place, and how to protect your artistic capital in this part of the world. And it also probably came from the tradition of Schindler and Gregory Ain and a group of people we all rejected but who were still there somewhere rattling around in our brains.

Your generation started in a much more conceptual territory, and it seems to have the opposite problem. I accepted a simple, generic palette, and I find my architecture spatially, organizationally, and other places. You guys: the materials haven’t been invented yet to accommodate your formal language and your aspirations, the desires you have that come with the nature of that language.

A lot of you put larger demands on the conceptual part of your work. You aren’t in any way burdened with those types of realities or even the potential of those realities. That’s going to limit the type of work—installation versus small-scale versus large-scale project—but it probably should. Something important about being 30 to 40 years old: your job description is establishing your intellectual, conceptual, artistic priorities. That’s your job.

Erdman: Did you feel that way yourself?

Mayne: Absolutely. In your 20s, you’re a kid still and you’re just—you’re trying to establish what the project is. In your 30s, it’s still very possible that your practice is not primary, which makes sense pragmatically, because nothing important is going to happen—in this country, especially—until you’re 50 anyway, or 45, if you get lucky. But the commissions will be farther apart and they’re going to be smaller scale, what people trust you with in terms of investment. And your job is to do your research.

In your 40s, you’re in transition. You’re emotionally more frustrated. You’re probably exhausting those ideas that are operating only on paper. And you should be ready— in terms of your energy level, your accomplishments, where you are in your artistic, intellectual project, in your research—to start testing. Teaching’s probably becoming quite different in terms of the questions you ask. It’s probably not as much first-principle; it’s now much more in sync with where you are in your work life and becoming a bit more pragmatic because of that—more synthesized, typological projects that are paralleling, possibly, your practice, but much less investigations into broad theories that don’t even relate to building.

It seems impossible to get out of that when you’re young, to win a major competition at 35—which can be, by the way, a horrible thing. As many times as it’s made careers, it’s ended careers, because you’re not ready. The Koreans talk about making opportunity, and when you get an opportunity, you have to be prepared to utilize that opportunity. You had to have gone through these stages in some fashion to be able to utilize it.

Erdman: In L.A., there’s a legacy of people going fully through the evolution you outlined, whereas on the east coast it seems very few fully make it through that cycle.

Mayne: New York—I’ve been a transplant there my whole life, because of the architectural scene—living there now, I’m starting to realize it’s a centralized city, power-wise, and commodity capital is so powerful that it’s extremely difficult, especially for architects. Young architects get consumed by it. It’s the city of Warhol, and it just swallows you up.

But L.A., for whatever reason, is still an institutionalized anarchism, it allows for a certain creativity and freedom and autonomy. Two powerful things in my generation were seeing architecture as an autonomous activity and that autonomy as connected to resistance. Not the resistance and autonomy of modernists in the manifesto. A much more calculated, much more personal, private, diminished objective. But still absolutely connected to resistance. It’s still incredibly important, the political nature of architecture, part of my practice and my person. I would have said it’s a little different in your generation.

Erdman: It’s a big difference. There’s been a kind of apolitical posture . . .

Mayne: And with that goes the resistance. There’s nothing to resist. I think that’s going to change. Every generation develops at its own rate, and part of that development isn’t psychological or personal. It has to do with the general environment, and maybe in some simple way it has to do with what’s going on right now with the current political scene, with Obama, that he seems to be bringing in large numbers of young people who go up to your age, the 20 and 30s who, if they haven’t been disgusted by government, find it totally irrelevant. And he seems to be galvanizing a whole new group of people.

The thing that changed me the most— when I hit, say, 50, I was with Richard Weinstein and we were walking and talking and looking at this and that, and he turned around and said, “Thom, you’ve finally done it. You’ve connected the social act and the aesthetic act.” For him, that’s the definition of architecture. And it was for me, too. I felt it was like the first building I had ever done, the first time I’d actually affected society. I did something that could shape behavior, that in some small way . . . Forget the modernist—I’m not talking about it in those terms, that architecture’s going to change the world. We’ve been there. But, in fact, in some way it can change somebody’s life.

For architects, there’s a huge amount of serendipity involved in your development, which you have no control over. It’s been frustrating, because I’m a person who would like to have control over my own destiny. Something takes place that will completely change the responses you as an architect need to make to resolve the problem. At that point you’re going to have to say, “No, I’m not ready. These aren’t my interests, so to move from this project to that project is actually going to harm me, because the distance is too great, and I need some sort of a ramping up to maintain who I am.”

At 45, I was so pissed off I could barely talk to anybody, because I was ready to do that work. And now I look back and say, “Actually, really, I wasn’t quite ready to do what I thought I was ready to do.” I was thinking about it in design terms, and maybe that was correct. But I wasn’t thinking about the complexity it takes to accomplish a project on a certain scale, which takes an organization that you’ve built up so that it’s not you anymore, it’s your culture. It’s you as a thought leader, with the authority and the strength and the talent to bring people together and multiply your ability to deal with complex problems.

I’m working on this project in Paris right now with a group of people who are taking big pieces of it, and I went over and did a charette. We had to make a huge amount of changes. And I came back and—I don’t mean to be bragging—I was really proud of myself, because I got a lot done in five days, and I was able to solve a huge amount of stuff. I can get my arms around a vast project that has thousands of variables, and I was joking with my wife, “Damn, I actually learned some shit all this time.”

David Erdman was the principal of servo’s Los Angeles office before establishing david clovers in 2007 with partner Clover Lee. His work has been exhibited at the Centre Pompidou, MoMA, San Francisco MOMA, Artists Space, and Biennales in Venice, Korea, and Beijing. He teaches at UCLA and is currently the Cullinan Visiting Critic at the Rice University School of Architecture. He is in conversation with Thom Mayne, FAIA, founder and principal of Morphosis.

Originally published 1st quarter 2008, in arcCA 08.1, “‘90s Generation.”