Imagine the proverbial tabula rasa for designing a new twenty-first-century university campus. Infuse it with a mission to explore the very nature of human health and existence and then place it in the largest underdeveloped parcel of what is arguably America’s most beautiful city. Throw in a few public agencies, neighbors, civic leaders, philanthropists, university regents, administrators, faculty and students, and then decide what it should look like. The biggest challenge in the design and construction of

UCSF’s Mission Bay campus may very well be the process of getting there.

A recent comparison of real estate development was made between Chicago and San Francisco. One city, notorious for great architecture, celebrates the end product—the built environment resulting from development. The other, notorious for extreme views (political and physical), is very concerned about the social environment that may or may not lead to development. In this San Francisco context, a new campus with aspirations for great architecture is rising.

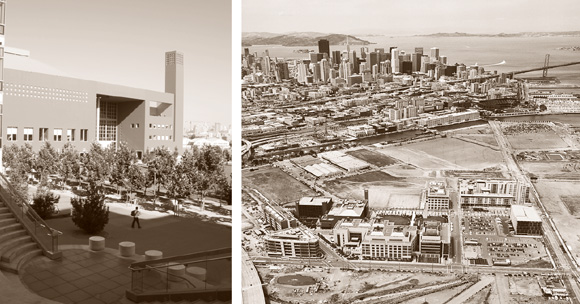

The new forty-three-acre UCSF Mission Bay campus is situated on former rail yards about fifteen blocks south of San Francisco’s financial district, with the bay to the east, the Potrero Hill residential neighborhood to the south, and an elevated freeway to the west. The campus is to become one of three primary locations, among more than two dozen other sites, which UCSF occupies throughout San Francisco. Could this new campus forge an identity for UCSF, a university at the top of the nation’s academic medical centers, but historically outside the general consciousness of higher education due to the absence of undergraduate programs and sports? How much would architectural design and campus planning impact the formation of identity? How would the Mission Bay campus relate to UCSF’s other sites?

Starting from a blank slate is a powerful moment. Most of our urban architectural opportunities arrive steeped in surrounding context. While significant form generators for the Mission Bay campus include technologically complex biomedical research laboratory programs, defined massing envelopes, and the unique quality of San Francisco light, the question of architectural identity relative to the degree of overall uniformity looms large. Do we build a Stanford quadrangle of stylistic singularity, or a new and improved Columbus, Indiana, the twentieth century’s architectural petting zoo?

The answer for UCSF has evolved from soul-searching introspection. To be expressive of its health sciences mission, principles of collegiality, cohesiveness, and connectivity were identified to guide design. The competition-winning campus master plan — by Machado Silvetti / Chong Partners — diffused boundaries with the surrounding neighborhood, consistent with UCSF’s community service role, being not only in, but also of, the city. Design has proceeded with diverse international and local architects working within a framework of principles, materials, and massing guidelines not unlike the individual and collaborative art of biomedical research.

Seven buildings of more than 1.5 million square feet and a 2.5-acre green have been completed in the past four years, with another now in construction and two more in design. Buff-colored travertine clads most exteriors. Eighty-five-foot-high façades offer a range of interpretation of the classical base-body-cornice composition, from literal to abstract.

Prominent entrances punctuate all buildings, and exceptions to rules abound. Laboratories of refined travertine with tinted windows— by Zimmer Gunsul Frasca with SmithGroup; Cesar Pelli with Flad; and Bohlin Cywinski Jackson—march along in contrast with the decidedly “happy” Golden Gate Bridge orange, blue, yellow, and fuchsia community center, by Legorreta with MBT. A 760-bed student apartment complex, by SOM with Fisher Friedman, features four wings and two pavilions of varying heights framing courtyards that participate in a linked network of major and minor open spaces designed by Peter Walker and Partners.

At the main pedestrian entrance stands a parking garage by Stanley Saitowitz, clad in translucent glass panels arrayed to communicate “health sciences university” in its referential DNA fingerprint. Under construction is a cancer research building with stepped and interlocking labs and offices by Rafael Vinoly with Gicklhorn-Lazzarotto, which forms the symbolic northeast cornerstone of the campus. In the six years since ground was broken, several key decisions have transformed UCSF Mission Bay from the originally feared “academic Siberia” into a new center of gravity.

Rapidly establishing critical mass proved essential, enabling the principles of connectivity and cohesiveness to play out not only architecturally, but programmatically as well. In the fast-moving world of biomedical research, physical proximity still trumps the Internet for collaboration.

Another key decision was to borrow the lab “neighborhood” floor plan—wildly successful at the main Parnassus Heights campus—as the building block for Mission Bay. An integrated public art (Serra, Balkenhol, McMakin, Borofsky, Larner, Isermann) and architecture program is creating an aesthetic environment intended to stimulate the duality of art and sciences in biomedical research. And despite the programmatic and economic imperatives to maximize research square footage, early investment in a community center and large public green has formed the heart and soul of the campus, as well as the welcome mat to the surrounding city and UCSF’s other campuses.

It is this linkage with faculty, students, and staff at other UCSF sites that is perhaps the biggest challenge today. The insulated, inward-focused academic campus is relegated to urban planning’s history books. As decisions are made on the best interdependent use of its many sites, UCSF is exploring how to become a new model of the urban, interconnected, multi-site university.

Author Steven Wiesenthal, AIA, is Campus Architect and Associate Vice Chancellor for Capital Projects and Facilities Management at the multi-campus University of California San Francisco (UCSF) and Project Director for the university’s new 43-acre, 2.6-million-square-foot Mission Bay campus. From 1991 to 1999, he was Associate Vice President for Architecture and Facilities Management at the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center. Prior to 1991, Wiesenthal was an architect and planner with Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, where he designed and managed projects for Dartmouth College, UCLA, Penn, and Harvard.

Originally published 4th quarter 2006 in arcCA 06.4, “The UCs.”