At the height of the first Covid-19 lockdown, a generally uncertain time, I applied to a research fellowship at EHDD architecture with an ambitious proposal: to build a tool for identifying a path to Climate Positive on every one of the firm’s new projects. For the first two years I worked for EHDD, I worked from my living room in New Haven, Connecticut. The uncertainty of everyday life at that time was compounded by the uncertainty in the project itself: the idea might have been ambitious, but it also had no clear path to success. Despite this, we kept working at it. Two years of blood, sweat, and spreadsheets later, the tool is available to everyone as a web application called EPIC—the Early Phase Integrated Carbon assessment.

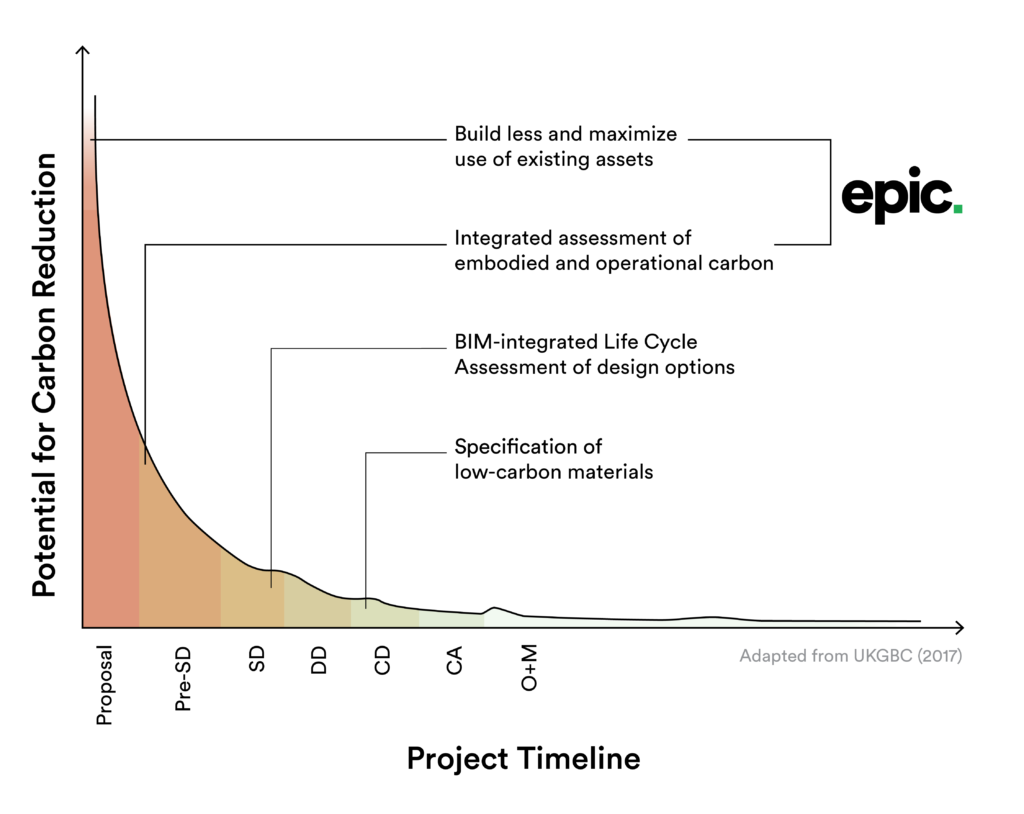

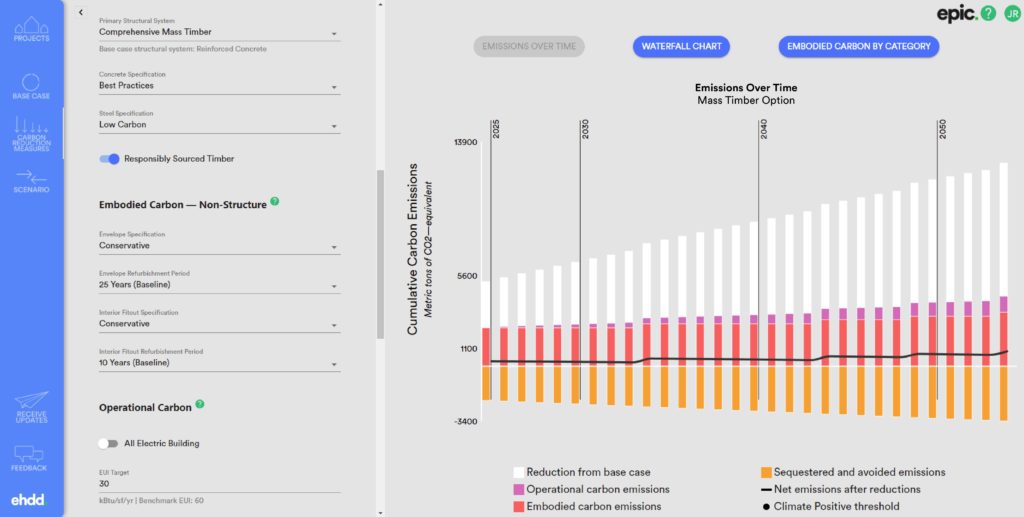

There are countless stars that aligned to bring EPIC to light, but one shines brightest—EHDD took a risk on innovation at a time when other firms were shoring up their core business. But with the climate crisis all around us, there seemed to be little sense in banking on business as usual. Our “innovate as we go” approach proceeded iteratively—from sketchy diagram to data source to data crunching to calculation, then back to the beginning—refining our calculations over time. We went through multiple rounds of external peer review, a few of them rather harrowing, as we worked toward an approach at the correct level of resolution and completeness to give quantitative support to early phase design decisions, when data is scarce but the potential for emissions reduction is high.

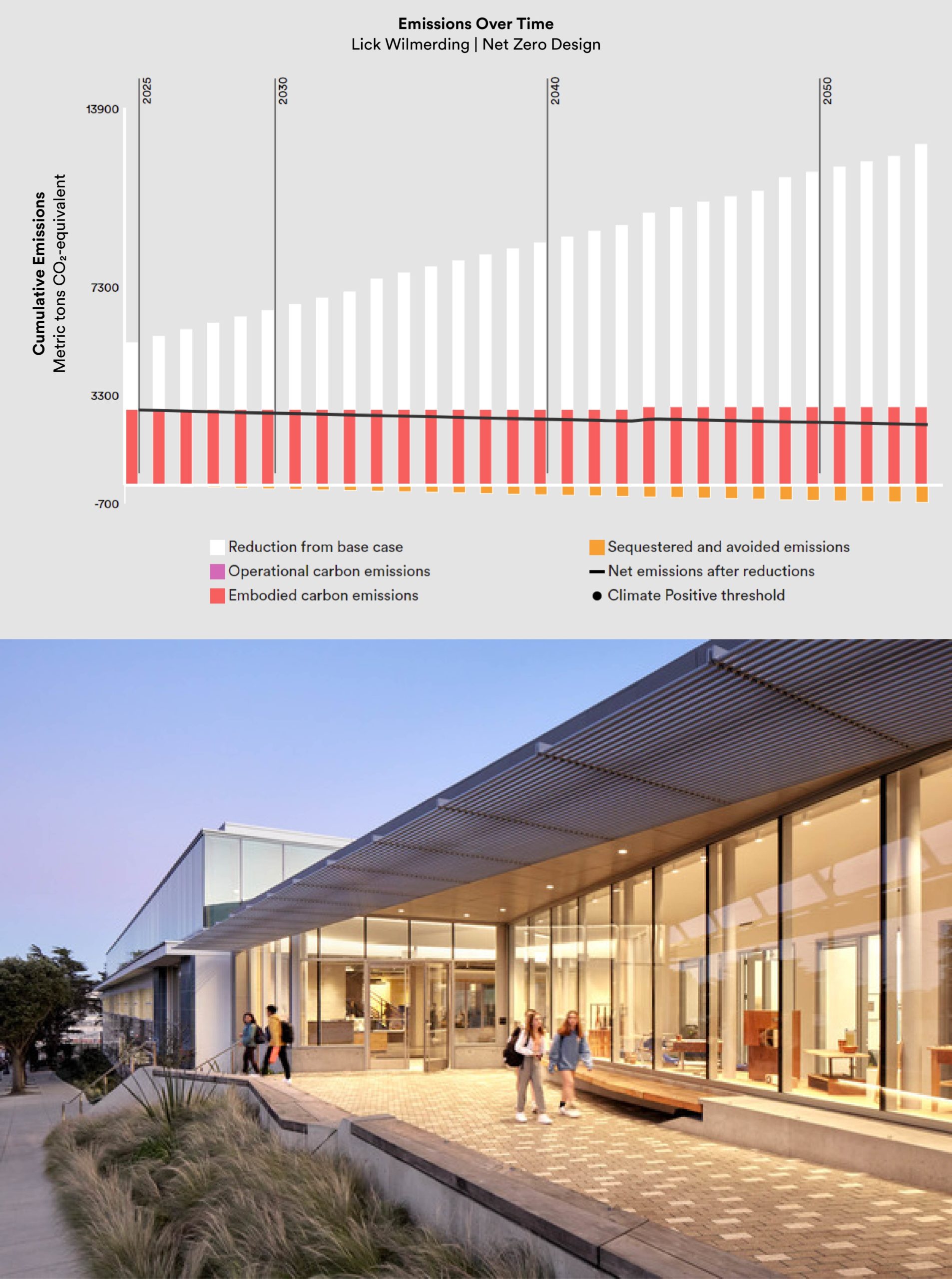

An early test of the project came when we were putting together the RFP for the renovation of the AIA National Headquarters. As part of our proposal, we modeled a decarbonization pathway for the project that included both energy-related “operational carbon” and material-related “embodied carbon.” EPIC also included estimates for things like furniture, which are often ignored but would represent a large proportion of the emissions from the renovation. The AIA made the commendable decision to offset the project’s embodied carbon emissions via the installation of solar arrays on local affordable housing, eschewing the low-value, low-cost offsets that are typically purchased. It was an inspiring approach, whose feasibility was staked on our early carbon assessment with EPIC. Now the project is nearing the end of CD, and we hit the goals we set early on. Our team’s recently completed and finely detailed carbon assessment was within 5% of the EPIC estimate. Grappling with uncertainty early on in the project helped us to set targets and meet them.

When we started work on the AIA proposal, we had already distributed EPIC for free to around 120 peer firms, many of which with their own sustainability credentials. Some of those firms are direct competitors. This first round of users was generous with their feedback, which we did our best to parlay into improvements to EPIC’s data, its presentation, or its user’s guide. We have always tried to take feedback from our users seriously. It’s a win-win proposition: they provide us with information we need to improve EPIC, we provide them with the tools they need to support low-carbon design decisions, and the exchange itself strengthens a community of practice focused on building decarbonization.

Since we launched the EPIC web application during the 2022 AIA National Conference, happily coinciding with the summer solstice, this community of practice has grown enormously. As I write this, we have about 1,200 users and more than a dozen unique logins each day. To preserve data privacy, we don’t keep track of who these people are or how they’re using EPIC, but I engage with a few users who are interested in vetting our assumptions, checking data sources, or asking follow-up questions. Recognizing that reaching out to us with a set of questions is itself a form of generosity, we do our best to respond to these questions quickly and comprehensively.

Correspondence that began with questions about EPIC has led to wonderful role reversals. I’ve had the pleasure of watching from the audience as users from both very small and exceptionally large firms present EPIC to clients, at conferences, or to their firm’s leadership. On a personal level, it’s deeply gratifying to broaden this community of practice. On a strategic level, a decarbonized building industry is better served by broad fluency than by concentrated expertise. The idea that climate action should be the domain of experts is, in my view, backwards. We need open access tools to catalyze action by every designer on every project, not just by the right people on the right projects.

I am looking forward to the day when zero-carbon is no longer a differentiator but the baseline. By making EPIC open access, there’s massive potential to lower carbon reductions from a much wider swath of projects than any firm-specific effort. That was, full stop, EHDD’s reason to offer EPIC free for public use. There’s no sense in putting a padlock on a fire extinguisher when the world’s on fire.

Beyond expanding our impact, our tools are stronger for being freely accessible. The light of day has a salutary effect: open access tools are better tools. I’ve had a chance to peek under the hood of a number of similar models maintained behind closed doors and, in them, rough assumptions run rife. Unchecked, these assumptions are dangerous. EPIC is, in my estimation, a better tool for being subject to scrutiny and criticism. Plus, architects (and their clients) are a sophisticated audience. A “trust us, we’re experts” attitude, obfuscation, and overly simple statements are a nonstarter. To satisfy our users, we do our best to be forthright about our shortcomings, be transparent about our assumptions, and draw attention to the real sources of uncertainty.

Work on EPIC has been expensive—we whizzed into six-figure territory right after public launch—but not without its upsides. While we are not yet breaking even, we have gotten significant interest and some funding from organizations working in ESG [Environmental, Social and Governance] investing who are interested in integrating our data models of building emissions into their own product offerings. Whether or not this funding ever does more than help us break even, our work will remain focused on maximizing positive impact. Five-sixths of all profit generated from our work on EPIC will be reinvested in improving our models and expanding their use. Toward this, we’re currently piloting a version of EPIC to support Climate Action Planning and policy efforts.

EPIC, of course, is far from the only carbon assessment tool out there. As tools proliferate, it’s more and more urgent that users have clarity about what results are comparable and which aren’t: if two tools make similar claims but give dissimilar results, then the reputation of both tools suffers. This reputational risk underscores the importance of collaboration between tools offered by different organizations. To avoid this, we share our data and methods with Architecture 2030’s CARE Tool, which focuses on building reuse. Our work is complementary, and both tools are stronger for our collaborative approach.

The “red queen’s race” from Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass is an apt description of the role of innovation in our practice: “It takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that!” It’s shifting some, but our goal of a decarbonized built environment still faces significant headwind. To fight this headwind, we need to move fast and move together. This, as I see it, is the role of collaborative and open innovation.

Other freely available tools developed by architecture firms and related industry organizations include:

CARE Tool (Carbon Avoided: Retrofit Estimator), developed by Architecture 2030 to compare the total carbon impacts of renovating an existing building vs. replacing it with a new one.

Building Transparency’s EC3 (Embodied Carbon in Construction Calculator), a free database of construction Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) and matching building impact calculator for use in design and material procurement.

Kaleidoscope, designed by Payette to quickly compare the embodied carbon impacts of various standard building systems and design options.

Ladybug Tools, a collection of free computer applications that support environmental design and education.

Transparency, Perkins+Will’s guide to potentially hazardous chemical content of building products.

The above are all interactive, digital tools, but firms have also developed text-based tools, such as Mithun’s Mariposa Healthy Living Toolkit, a guide to assess the health conditions of residents and identify opportunities for improvement through the built environment in urban redevelopment projects.

Author Jack Rusk is a climate strategist at EHDD, an architecture firm with offices in San Francisco and Seattle. He is the lead developer of EPIC, a tool for low-carbon design available for free use at https://epic.ehdd.com.

From arcCA DIGEST, Season 13, “Innovation.”