Los Angeles is a complex plaid of a city, streets running North/South and East/West, carving up a submissive landscape into cities and neighborhoods without regard for geology, topography, or natural features. The pattern is simple and indifferent and virtually without organizing force other than the crude mechanics of commerce. Which is why the city of Paramount is filled with steel fabricators, why San Fernando has more than its share of stone yards, and why the town of Gardena is home to a cluster of casinos, pawn shops, and purveyors of guns and ammo. Yet in Gardena is an improbable gem of a building built by Larry Flynt and housing his Hustler Casino, part of the ever-expanding Hustler empire. By virtue of signage as well as its distinctive profile, the casino asserts its presence at the corner of South Vermont Avenue and West Redondo Beach Boulevard. Although the architects, Ron Godfredsen and Danna Sigal of Godfredsen-Sigal Architects, sold the design to Mr. Flynt as a stylized crown, it comes across as a makeshift tent thrown up at some desert oasis. But this is no ordinary tent; made up of tilt-up concrete panels, the surface is articulated with a continuous pattern of twelve-inch pyramids that renders the skin as a light, billowing, tufted fabric perforated with colored circles and ellipses. Not until you get close do you register the construction joints and sense the structure’s massiveness.

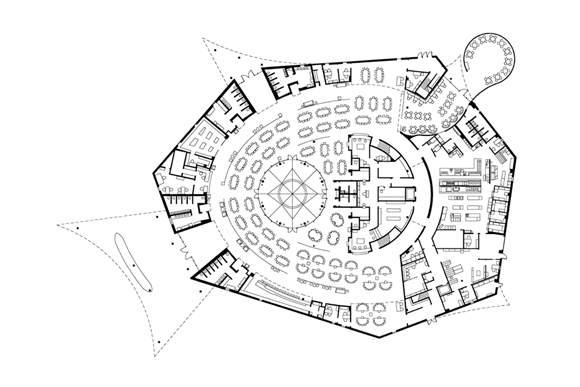

Inside you see why this concrete tent was thrown up in the first place—to conceal an immense alien spacecraft charged with drawing in unsuspecting humans and sucking the life out of them, presumably to fuel extra-terrestrial life in Beverly Hills and beyond. The metallic belly of the UFO, which curves up right to the burgundy-mohair-upholstered inner skin of the gambling pod, is punctuated at regular intervals by glittering ganglia masquerading as glass chandeliers dropped from glowing red apertures. The center of the spacecraft is carved out and open to the sky for smokers but could easily double as a way station for the intergalactic transport of indigent gamblers. The petaled opening at the top of this conical room is both beautiful and terrifying as it opens and closes, a sort of man-eating Venus fly trap straight out of Little Shop of Horrors. The carpet is an over-scaled version of a Stephanie Odegard design, expanded to a twelve-foot repeat with colors drawn from the rest of the interior: gold, burgundy, purple. With the mohair walls, the looming underbelly of the UFO, the crenellated fortress of the sports bar mezzanine, and the delightful graphics program, the architects have created a gestalt strong enough to overpower the chaos and inevitable cheapness of the gambling tables, with their scantily-clad hostesses plying prey with food and drinks.

The design clearly appealed to Larry Flynt’s ego, summoning all the requisite tropes of royalty; yet it did so without sacrificing conceptual rigor. Informed of the client’s distaste for modern architecture and love of Victorian, die-hard modernists Godfredsen-Sigal sought common ground. They presented the work of the Secessionists and hoped Mr. Flynt would be responsive. He was. Drawn to the use of color and gold leaf—not to mention the subject matter—he encouraged the designers to follow the palette of painter Gustav Klimt. (At the same time, he commissioned a series of Klimt knock-offs for display in the Casino.)

The result is an unexpected synthesis; as art critic Jan Tumlir puts it, “This is what good design has always done, seeking the ideal solution that would reconcile and integrate the various oppositions—the perfect fit.” Such a strange, unanticipated merging of a client’s desires and an architect’s skill has produced a work so completely imagined and so scrupulously realized, it can only give birth to tragedy. Leave it to entropy or to greed or to the state of architecture in America, time would not be kind to the Hustler Casino. Even before the building had been completed, a dispute between owner and architects caused an irreparable rift, severing the delicate chord that united, for the briefest of moments, their disparate visions: in addition to committing minor design infractions, management has already engaged another architect to do an addition. So, as the power of the Godfredsen- Sigal design erodes over time, the Hustler Casino will become—sadly, for us as architects— just another casino in Gardena.

Author Tom Marble, AIA, is a partner with WhiteMarble, a multidisciplinary design firm in Los Angeles.

Originally published 2nd quarter 2006 in arcCA 06.2, “L.A.”