On the surface, I do not have a lot in common with Thomas Jefferson. For one, he’s dead and I’m not. Then there’s the fact that he was a man and…I’m not. Furthermore, he lived on the East Coast and never saw the Pacific Ocean, while I live a five-minute walk away from its sunny shores.

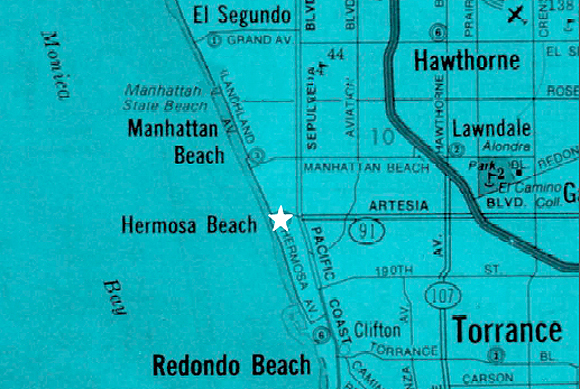

Still, there are a few important areas where Tom and I are somewhat similar. He was an architect and so am I. And though I have not yet become president, we have both been deeply involved in politics. I am a two-term mayor and city council member of Hermosa Beach. This, apparently, makes Tom and me rather unique. There are—and have historically been—very few architects involved in politics.

Certainly it was not with any zealous forethought that I chose to correct the professional imbalance by storming the ranks of my local city government with protractor and parallels. I was very busy as an architect, business owner, and thinking of starting a family. The demands of the building industry, family needs, and necessity of making a living tend to keep architects focused on architecture.

This, in fact, I see as the most plausible reason why there are so few architects in the halls of both national and local government. We are not a consistently well-paid profession, and most often cannot afford the time required to run for and hold political office.

Why, then, did I decide to mix these usually unmixed activities? Perhaps how I did it will answer the why.

In 1987, my husband Lee and I started our architectural company, Oakes and Associates. Energetic and somewhat foolish, we gleefully began the roller-coaster ride of the architectural business owner. Locating on what was then the Santa Monica Mall—a run-down outdoor shopping area—we became involved in the efforts of the city, a newly formed business assessment district, architects like ourselves, and the community to create the very popular Third Street Promenade out of the old “mall.”

At about this time, we bought our first house in the beach community of Hermosa Beach. Immediately, I could see that my experience with the Third Street Promenade could be of use to this community of lovely beach front homes and its deteriorating downtown. I put together a design package. It was a set of fairly typical architectural responses to a community’s need—create a plaza, improve the landscaping, signage, relax parking standards for diverse types of business, etc. I cited examples of our involvement on the Third Street Promenade—both in private development and public projects, e.g. our involvement in creating the outdoor dining standards, streetscape improvements, pier circulation, and entry treatments. I included sketches of what could be done for downtown Hermosa.

I submitted this to the city council and…heard nothing. Not that I expected an immediate opening of the floodgates, but nothing? My proposals, however, had not been ignored by all. A few months later, an incumbent city councilman running for reelection came to my house and asked me to volunteer for the planning commission. A movement was afoot in the community to improve the downtown; they needed help figuring out how to implement it.

Clearly, the built environment is a reflection of a community, and ten years ago when I started out in public office, that reflection in Hermosa Beach was a bit tired and run-down. So, seemingly, was the attitude in and around City Hall. When I would ask why things had not changed before, I typically got the response, “We’re just Hermosa Beach.” Clearly, my first challenge was to build a coalition and change this torpid attitude. Then, we could get down to some real building.

It became evident to me that the concerns and challenges put to a planning commission, indeed any commission, are ultimately taken up by the city council and mayor. Driven by my desire to continue the process and see the community turn around, after two years on the planning commission, I ran for city council and won. I can only guess why I was chosen out of the twelve other people running that year. Perhaps because the community knew it had a mission of revitalization before it, and, with my professional and company background, the voters felt that I could lead them down a focused path towards that exciting—and buildable—community vision.

Architects are uniquely well suited and trained for a role of leadership. It is my opinion that architects can go into the political arenas with the challenges of juggling family, profession, and political life more adeptly than other professionals. We can think in three dimensions and visualize the impacts of developments and planning and zoning changes. And we are able to envision a future that cohesively brings together the ideas of many.

As mayor, running the city was much like running my company—but on a large scale. The city council came to rely on me for opinions on the various aesthetic considerations and land-use issues. The issues of water concerns, energy needs, and impositions on open space, agricultural lands, and wildlife lands are going to be increasing challenges as California continues to grow and create further demands on our environment.

My desire was not to change the whole shape and structure of our community but to deal with the meaningful details in a coherent way. City departments, for example, are expected to create public structures that are safe and easily maintained. This is usually interpreted to mean structures that have no regard for design, quality, or innovative use of materials. But is the best solution simply to meet the bare minimum requirements? Or could we create not just a more sanitary and convenient environment but one that would enrich the image of the community, as well?

Such questions are relevant to all community projects. For instance, the remodeling and replacement our park and beach bathrooms would cost about $30,000 more per structure to create more airy wood roof lines and use better quality materials on the interiors. Some of the council members worried about this. My response, however, was that these structures would be a reflection of our community—no matter how large or small. In the 20 or 30 years that people would be using them, would these buildings invoke a sense of place or, I asked rhetorically, would people say as they walked away, “Gee those are ugly, but, gosh, we saved $30,000?”

I don’t think so.

We maintained our company offices in Santa Monica for ten years and Culver City for another five. This year we have opened up our Hermosa Beach offices. Having a company that has been in existence for fifteen years, winning awards and creating large, successful projects, has helped assure others that my success was already in place when I went into politics and that I was not dependent on political gain to make my career and company.

One might ask, however, how my political position helped my company. On a day-to-day basis, it has not helped a whole lot. In fact, there have been few professional benefits from my tenure as leader of a community. But there have been subtle advantages. I now have a perhaps overly confident sense that I can walk into any city we are doing work in and go right to the top if need be. Although I have not pushed this, many city engineers and plan checkers in various cities are aware of my status, and maybe that makes a difference, I don’t know. I was always politely pushy at building departments even before my political career.

And then there are those who have tried to push advantages my way. I remember one incident with a private developer who had a commercial development up for public review in downtown Hermosa. He knew it was fraught with problems that the city could not accept. Unwilling to make changes to his plans, he called me one day. He knew of our architectural company, as we have a number of commercial developments in cities that he is working in. He explained that, if I could see my way to allowing his project to go through in Hermosa, he would certainly like Oakes and Associates to do some of his projects in other cities.

While I like to eat, I like to sleep at night even more. I remember telling him that, since he thought we were such a great architectural company, I fully expected him to look us up…despite the fact that I was not going to approve his project. Needless to say, he hasn’t called.

The personal benefits have been enormous. I am proud of the work the city has accomplished, the new plaza, parking structure, skateboard park, tennis recreation area, remodeled parks, the pier renovation, and the list goes on.

There are many roles that architects have and can have in and around City Hall. Architects now serve on many planning commissions and boards. But to implement policy and change, one must go further. Not all are cut out for the life of mayor. My husband and fellow architect has no desire whatsoever to pursue a political position. Why me? Admittedly, I enjoy being a leader. I am not sure how my family takes to that, but they have survived and so has my company. It was my architect background that brought me in, but it was my leadership desire that kept me going.

Where I will go from here, I do not know. I enjoy the political arena and I enjoy architecture. Perhaps I will pursue a higher political office or some other role that my political and architectural experience can benefit. I do know that communities can only gain from having more architects share the reins and use their skills to envision more practical and attractive environments.

I do not know if anyone has suggested that Jefferson was as good a president as he was because he was also an architect, but it might, just might be worth looking into.

Author Julie Oakes, AIA, is principal of Oakes and Associates and is the former mayor of Hermosa Beach, California.

Photo illustration by Supreeya Pongkasem.

Originally published 2nd quarter 2002, in arcCA 02.2, “Citizen Architects.”