__________

Why the San Joaquin Valley? What prompted your interest in hosting a research studio here?

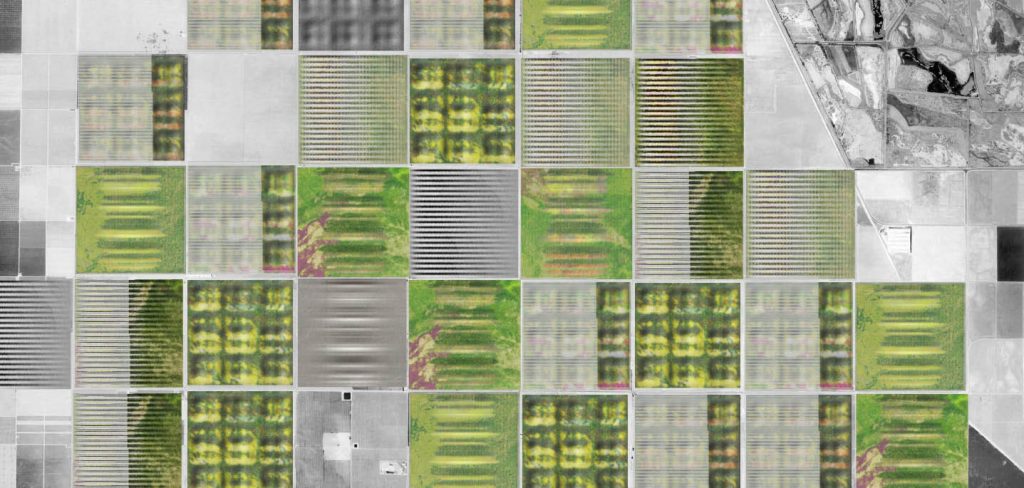

I chose the SJV because it serves as a nexus of some of the most pressing environmental questions of our day, particularly as they pertain to global food production, including climate volatility, rising temperatures, exhausted water systems, degraded air quality, contaminated soils and groundwater, food insecurity despite the agribusiness economy, extreme environmental and social inequity that is the manifestation of generations of discriminatory practices, and unmanaged growth around its urban centers. More positively, the SJV—and Fresno in particular—has been the host to immigrant populations throughout its history who have shaped the character and culture of the region. It is a landscape of extremes but its cultural resilience provides a sense of optimism.

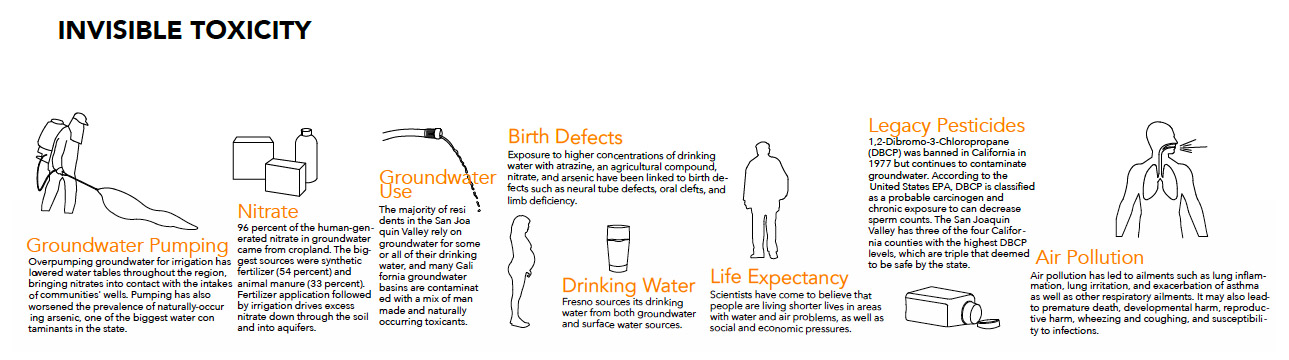

What are the most alarming health effects being imposed by the agriculture industry on the region’s laborers, inhabitants, and the environment?

There are definitely more qualified people to talk about public heath in the valley, but I can offer a short description of health issues our students directly tackled. Pesticide exposure and drift have had the most resounding impact on the soils, water, and people of the area. Mismanaged water resources, mostly highly engineered, have forced many communities—particularly those unincorporated or outside city municipalities—to rely on wells for household water, much of which is contaminated. This has unequally impacted poor communities of color. The air in the SJV has been ranked the worst in the country. High levels of particulate matter are caused by a variety of industrial processes, including machine-shaking of almond trees for harvest, as well as unpaved roads that serve the plentiful trucks essential to agricultural operations. The logistics of shipping and distribution create high levels of ozone emissions that get trapped in the “bowl” of the Valley. Agricultural burning contributes to this, as well. There have been improvements, but the air quality certainly creates health risks. Obviously, with rising temperatures, farmworkers are more vulnerable to heat-related illnesses. Food insecurity leads to other health challenges, including malnutrition and diabetes.

What were some notable discoveries from the fieldwork in the San Joaquin Valley? Were there any unanticipated outcomes?

The students were asked to be exploratory. The course was a final “capstone” investigation into landscape processes and strategic thinking about how to overcome some of the most extreme environmental challenges we currently face. Every one of the students uncovered the unexpected and arrived at proposals that were far from preconceived. This was largely because the students have been looking at predominantly urban landscapes throughout their studies, rather than focusing on production landscapes that service those urban areas. A couple of students were amazed at the cultural histories of immigrant growers in the Fresno area, particularly the Hmong population. The survival of small growers in this competitive market became a focus of their investigation.

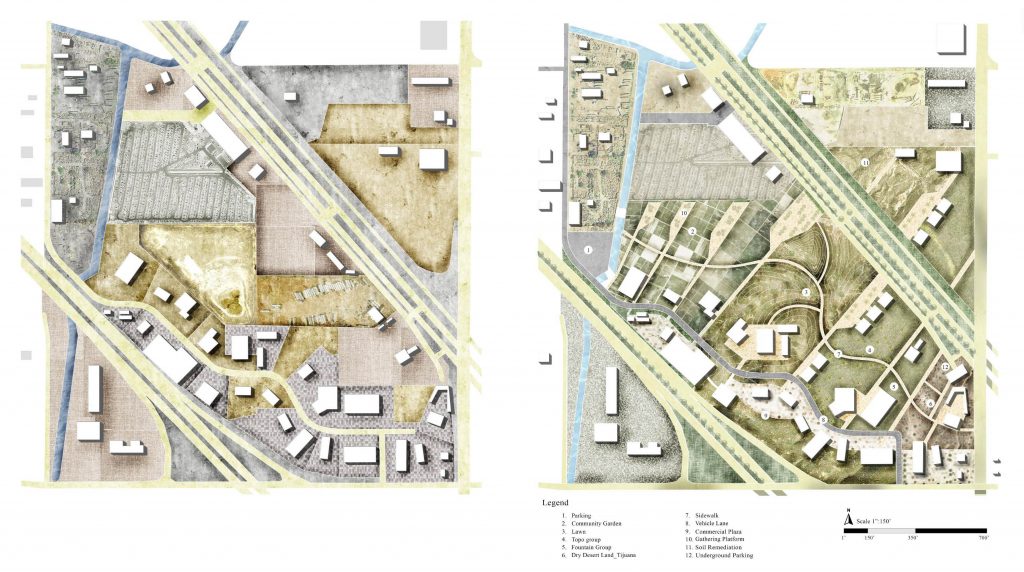

Students presented design proposals and prototypes to civic leaders, community organizers, and design professionals in the region. Can you describe some of these design proposals? What feedback was given? What are the next steps toward implementing design solutions? Toward influencing policy?

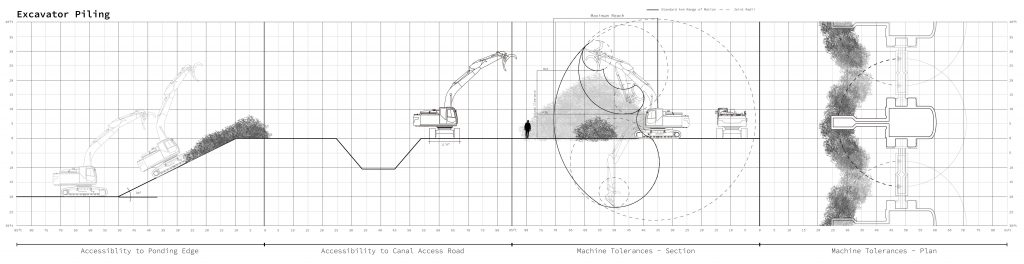

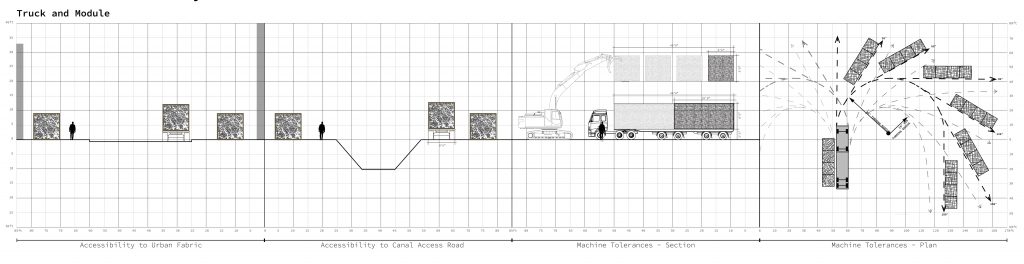

One student, Sarah Swanseen, developed a proposal that addresses the significant amount of biomass created by decommissioned almond orchards. Because the valley’s almond boom really began accelerating about 20 years ago, and almond trees begin to decrease in yield after about 20 years, many of these orchards are being pulled out, thus creating vast quantities of woody debris, which is typically burned (contributing to air quality issues), chipped, or transported to co-generation plants. This student wondered how this woody material might be used, particularly along the canals, to create habitat and ultimately to decompose, enriching soils and biodiversity in the region.

Another student, Alex Nuffer, focused on the “idle” or fallowed land in the Westlands that has been exhausted from overfarming, poor soil conditions and water depletion. He reframed thinking about agricultural “weeds” to imagine how they might be revalued and even contribute to our food systems through new cultural practices of foraging. Seed freedom was a major impetus for the early development of this proposal, recognizing the threat of corporate seed monopolies created by a small group of multinational agrochemical companies, which currently own about two-thirds of the global commercial seed market.

Another student, Yushen Liu, focused on the culture and spaces of trucking in the Fresno area, recognizing how segregated the spaces for transient workers are in the region. Many of the students were encouraged to continue their studies and prototypes and apply for grants that might facilitate further development of their ideas.

The United States is the world’s largest exporter of food, and the Central Valley is known as the “Bread Basket of the World.” Its economy is driven both directly and indirectly by the agriculture industry. What are the ramifications for the local economy of global challenges?

This month, the UN released a report, “Climate Change and Land,” which focuses most particularly on the impacts of climate change on our global food supply. The SJV is almost a perfect embodiment of these impacts, and yet many growers are not working to address a system that is on the brink of exhaustion. Some farmers in the valley, however—particularly young immigrant growers, many women—have started to introduce agroecological thinking and methods that focus on soil health, water conservation, and more balanced ecosystems. I believe these new growing methods—many actually quite ancient—have the chance to alter the agricultural ethos in the valley, even though the history of industrial agriculture is so deep there. Many large operations are just buying time, while continuing to use unsustainable practices. Other established, midsize-to-large growers are making incremental changes that have improved the outlook for SJV ag. Many believe financial incentives will be necessary to get more growers on board.

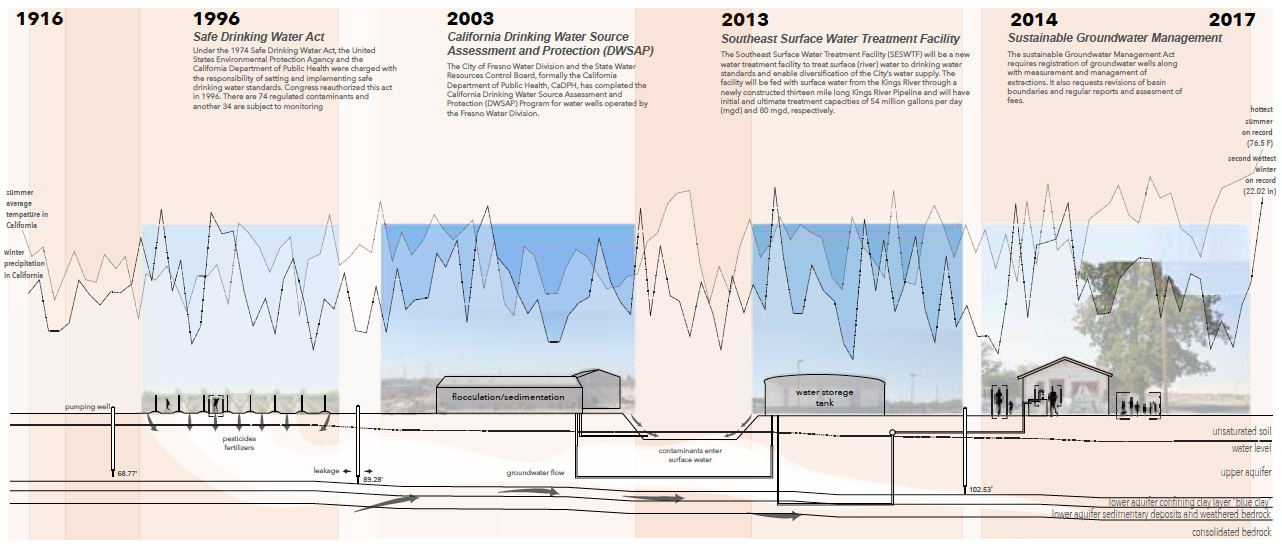

The Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) will have a significant impact on the landscape of the SJV. While it is an extremely positive step in improving the quality and quantity of groundwater in the region, and hopes for its implementation include introduced wildlife habitat and increased biodiversity, it is still unclear how it will play out. Will there be more financial stresses on small growers and, if taking the bottom-line perspective (which I don’t, usually, because I have the luxury of being in academia), who will “win” and who will “lose” when it comes to water and fallowing land? SGMA is at the scale we need to be thinking, however, if actual change is to be made.

The region is built on the labor of immigrants and their descendants, many of whom rely on agriculture for income. How do you see this workforce being affected by changing practices? Do you see a shift in skillsets similar to those caused by automation or industrialization?

Labor in the valley is so complex and, again, there are many who are more equipped to talk about labor issues, particularly in the immediate moment. It is, however, an area in which I am extremely interested, particularly as related to farmworker housing, settlement, and health. In terms of changes to the valley, yes, agriculture will change, and thus the skillsets and workforce will have to adapt and to some extent have already. Clearly, current immigration policies and lack of protections and services for immigrant workers are significantly impacting the agricultural labor force—causing increased labor shortages, heightened fears of deportation, and looser regulations for worker protection.

Typically, development on brownfield sites requires extensive analysis and remediation procedures. For over a century, urbanization in the San Joaquin Valley has been built on fields that have been sprayed with pesticides, herbicides, insecticides, and fertilizers. Should this be of concern as we continue to develop on formerly agricultural land?

Yes, this should be of concern. Soils and waters actively contaminated by innumerable chemicals are difficult to contain and remediate. Typically, poor communities of color have been most at risk, historically—often in unincorporated areas that do not have access to potable water. As an urbanist, I believe we need to be looking at infill development, rehab of existing building stock, while putting in place policies that don’t displace established urban communities. It is complex. This does not mean that experimental means should not be used to “clean up” contaminated sites—whether for urban development or continued/urban farming or other uses. This is an area that I wish my students had explored; one looked a bit at bioremediation, but we need more engagement with the sciences to bring together creative minds in thinking through future adaptations.

How can architects respond to and perhaps remedy the ongoing crisis in the San Joaquin Valley? How can we build for a resilient future in the valley? What initiatives should we promote to clients, the public, and our leaders? What policies should we propose?

At first, I felt very overwhelmed by the challenge of thinking comprehensively about the SJV, simply because of the scale, complexity, and abundance of “problems.” As I get deeper into my studies of this region, however, I realize the importance of a design perspective in the regional conversation. Particularly for landscape architects, who are typically highly skilled at synthesizing complex systems as part of a holistic creative process, the value of contributing is clear. Designers are able to take challenges and their complexities and imagine alternative futures, or help others imagine how the world might be conceived otherwise. This is on the grand scale. In addition, through targeted design interventions and built projects, designers can have more immediate, resonant impact.

To ensure the San Joaquin Valley can continue to be inhabitable for future generations, what is the one issue we should prioritize?

This question is extremely difficult to answer because all the “issues” are deeply intertwined. My passionate commitment is to find a way to use design to arrive at a more just and equitable world, so focusing on communities who have been left behind yet are integral to this place is a concern of mine, as is mass species loss. These concerns, however, are wrapped up in the issues of global capitalism, climate change, conservation, immigration policy, public health, urbanization practices . . . and so on. What I have discovered in my research on the SJV is there are incredible scholars, scientists, farmers and farmworkers, advocates, and other individuals deeply committed to the viability and health of their region, but it is difficult to bring all these concerns together to imagine how to work toward a comprehensively better tomorrow.

You are working on a forthcoming book, The Performative Landscape: Public Histories and Politics of Settlement. What can we anticipate from the work? Are you currently working on any other research projects?

It’s funny; I started my teaching and research on the SJV intending to write a chapter for that book-in-progress, The Performative Landscape, on the shifting differentiation between “landscape” and “the working country”—a dichotomy identified by the cultural theorist Raymond Williams in the 1970s. Yet, the deeper I’ve gotten into the research on the history of the valley as a landscape and on the current practices, policies, and dynamics, the more I am realizing that this chapter should be a book—and exhibition—of its own. A way of bringing together thinking about the valley as it has been shaped and how it might be imagined into the future. Of course, I have a lot going on with the new Directorship of the MLA+U program at USC and two toddlers at home, but this is the new direction of my work, it seems.

As the newly appointed director of the Master of Landscape Architecture + Urbanism Program, what is your prospective direction for the program?

Using the university’s complex regional geography (I’m including the SJV here) as its primary laboratory to generate and test responses to the planet’s most pressing environmental challenges, including the resounding impacts of climate change, rapid urbanization, social and environmental injustice, and the interface of nature and technology. Landscape architecture is a broad field that encompasses the design of the complex range of environments outside our buildings (while sometimes an integral part of buildings, as architecture increasingly integrates natural systems). Clearly, this affords an enormous range of potential sites, cities, territories, and regions of intervention. The program has begun and will continue to focus on pressures of urbanization on our natural systems, public spaces, and communities, urban and infrastructural frameworks, and how to utilize landscape strategies to shape those systems, spaces, cities, and infrastructures to imagine a more resilient future, socially and ecologically. I am guiding our curriculum to focus increasingly on opportunities for applied research that has real impact on the ground or in shaping policy. My aim for the program is to develop critical thinkers and design leaders unafraid to tackle some of the most contested landscapes and environmental questions of our day.

What message do you have to landscape architects and architects in the San Joaquin Valley and design community regarding current practices?

I am fundamentally an outsider to the SJV landscape. I was born in Manhattan and later moved to the immediate suburbs of NYC. I now live in Los Angeles after a long period of living in Philadelphia. I have immersed myself in the SJV for a short 18 months (and counting). It is those I have discovered along the way—folks who have grown up in the SJV and left and come back or never left—who have demonstrated to me a truly amazing commitment to place. Perhaps I am simply surrounding myself with like-minded people, but it has been really inspiring to engage with people so dedicated to improving their personal geographies rather than attempting to escape or leave it behind because of its flaws. And this applies to many of the architects I have encountered, who are focusing on projects that have the potential to both transform places in the valley and transform thinking about the valley’s future.

__________