In December 2017, the 281,893-acre Thomas Fire—at the time the largest wildfire in modern California history, since dwarfed by several larger conflagrations, including the 1,000,000+-acre August Complex Fire of 2020—ravaged the hills above the town of Montecito. Before it was fully contained, the rains came, with an estimated half-inch falling within a single five-minute period in the early morning hours of January 9, 2018. The bared earth gave way, and the resulting debris flows, up to 15 feet in height and moving at estimated speeds of up to 20 miles per hour, carried mud, boulders, and trees down a half-dozen of Montecito’s scenic canyons. Twenty-three people lost their lives; over 100 homes were destroyed and another 300 damaged.

At the request of the County of Santa Barbara, the Santa Barbara Chapter of the AIA (AIA|SB) put together a Community Recovery Team (CRT) to assist in the response. The work of the CRT is chronicled in the Thomas Fire / Montecito Debris Flow Community Recovery Team case study, edited by Robert L. Ooley, FAIA, and published by AIA|SB in May of 2020. The first entry in a library of case studies being assembled by AIA California under the guidance of its Disaster Assistance Network Chair, William Melby, AIA, the AIA|SB report offers insights into regulatory response to unprecedented circumstances, strategies for more resilient construction, and an instance of imaginative, collective repurposing of devastated property.

Permitting for Reconstruction

It is common for zoning and building laws to allow “like-for-like” rebuilding of homes damaged or destroyed in a natural disaster. As the case study reports, “[T]hese ‘relaxed’ rules would allow rebuilding in the same location, with the same (or very slightly modified) size and like materials. This method works well for rebuilding in anything but a debris flow event . . . [in which] the terrain levels can change dramatically. Where there was once a creek, is now fill-in land and where there [was] once solid ground, is now a creek. Where the ground elevation at the corner of [a] pre-event building pad might have been 100 feet about sea level, [it] is now 112 feet above sea level.” The County of Santa Barbara Planning and Development staff worked out alternative rules to accommodate such transformations, and AIA|SB helped communicate the proposed changes to decision makers and the public, leading to the adoption of a special ordinance by the County Board of Supervisors.

Strategies for Resilience

In workshops to advise homeowners on reconstruction, the CRT presented four principles for rebuilding more resiliently:

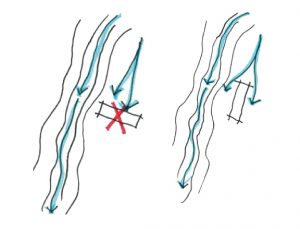

| Go with the Flow: lay out structures with their long dimension parallel to anticipated debris flow and design the upstream side to deflect oncoming debris. |  |

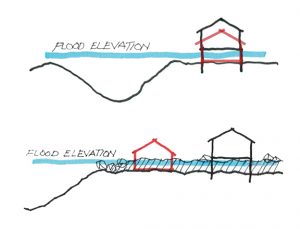

| Rise Above: raise the first habitable level of the structure above the new base floodplain elevation. |  |

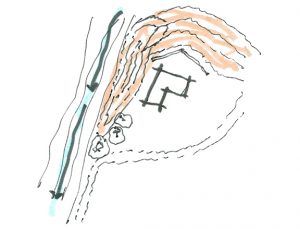

| Use the Land: retain soil deposited on the site by the debris flow and use it to create landscaped barriers to protect structures from future events. |  |

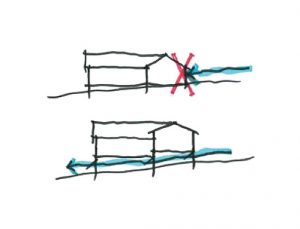

| Soft-Story Breakouts: design parts of the building that are below the base floodplain elevation so that walls will readily break away, so that the pressure of floodwater or debris flow doesn’t compromise structural columns. |  |

A Neighborhood Contribution

While strict logic might argue for relocating and rebuilding outside the area affected by the disaster, emotional ties to place and the intricacies of property ownership typically lead individual owners to rebuild in the original location. Such was the case in post-Katrina New Orleans, and such was the case, for the most part, in Montecito. One small group of property owners, however, made a different decision. On their own initiative, these residents of San Ysidro Canyon transferred their parcels to the county for the construction of a debris basin, which will protect downstream neighborhoods in a future event.

From arcCA DIGEST Season 07, “Concerning California.”