Arthur Golding, AIA, is the founder of Arthur Golding and Associates in Los Angeles. He is a member of the LA River Advisory Committee and Chair of the AIA LA River Task Force. He also teaches architecture and urban design at the University of Southern California.

Arthur Golding: I founded my firm in 1983. We have participated in a number of design competitions and charettes. We won the national competition for the Rancho Mirage Civic Center. Our design was a one story complex of pavilions planned around a civic garden. Unfortunately, it didn’t get built. We were the master planner for an expansion of the Loyola Marymount campus and the design architect for a central utilities plant and a school of business. We have also completed a supercomputing center at Caltech and some buildings at Pitzer College in Claremont. A great deal of our urban design work has been pro bono, and it informs our other work. Of course, we have been very involved for some time around the river system here and were part of a team that recently produced a report entitled Common Ground: From the Mountains to the Sea. It’s an overview open space plan for the double watershed of the San Gabriel and Los Angeles Rivers.

KC: Who were some of your mentors?

AG: At a great distance was O’Neil Ford: I remember reading that he played a major role in the revitalization of the San Antonio River and wondering about how that could be. A little closer was Ian McHarg. I heard him lecture on several occasions, and his seminal book, Design with Nature, remains an inspiration. The closest example was Emmet Wemple, an extraordinary man and landscape architect. He introduced many of us to the Los Angeles River and its potential.

AG: The process began about thirteen years ago, when I became interested in the urban design potential of a couple of large sites, unused rail yards near downtown LA. I participated in an urban design workshop, sponsored by the planning department and the NEA, in 1989, focused on City North, from Union Station and Olvera Street to the River. That was my first attempt to consider the Cornfield rail yard and its surroundings. That plan proposed a new, mixed-use urban neighborhood, with a school and small park, but made only an initial gesture to the river. A little later, I was one of the organizers of an AIA-sponsored design charette for Taylor Yard. Much later, for the River Through Downtown conference in 1998, I was part of a team that proposed a large park on the Cornfield site, reconnecting the center of the city to the river.

KC: What grabbed you about this issue?

AG: Early on I felt that the river offers an extraordinary opportunity to revitalize the city. The city has turned its back on the river. Turning its face to the river will transform the landscape and the city. As I learned more about the river, I learned that it was the reason Los Angeles was founded as an agricultural town. Looking beyond the downtown area, one sees that the Los Angeles and the San Gabriel Rivers form a large, interconnected system.

KC: How did this civic involvement change you as an architect?

AG: In terms of time and energy, my work is now equally weighted between urban design and architecture. Earlier, there was much more architecture; by that, I mean design of buildings. Urban design is concerned with design of the public realm. In its essence it is public work. One might be drawn to urban design issues out of an interest for the public realm, but you have to become involved in community- based efforts and in consensus building in order to move toward implementation.

KC: Do you teach your students about their civic role as architects?

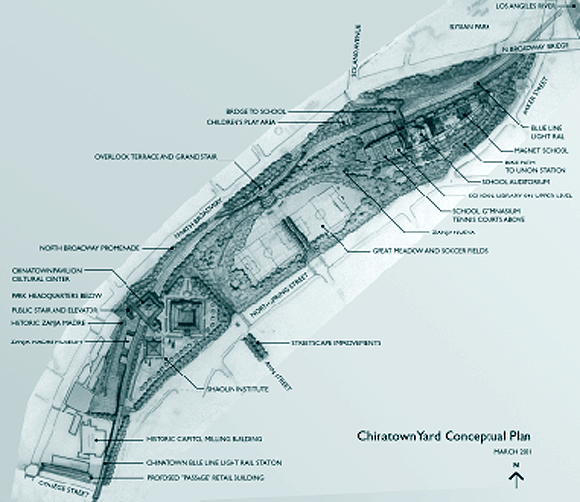

AG: Through the door of urban design. As part of the advanced curriculum at USC, students may select studios where they take on urban design problems. When you pursue urban design, you have to get involved in a process that ultimately becomes political. For example, we had students looking at the Chinatown Yards Cornfield site (above) and they got a sense of how the process really works. They attended community meetings and work sessions and interviewed participants and observed the messy vitality of competing points of view. It is interesting that, by the fifth year, students have relatively little sense of either the regulatory or political climate in which they will operate. There are larger political and theoretical issues, but I am talking about specifics—which jurisdictions have oversight and the different roles of various agencies and commissions. Every time I teach an urban design studio I am familiarizing students with relevant jurisdictional regulations and processes as well as the larger political scene. To be successful, urban design must engage the political life of the community.

KC: Which skills or strategies have been successful for promoting or pursuing the urban design issues around the LA River?

AG: Urban designers use an architect’s skills. Analytic skills that architects develop in organizing information and analyzing site conditions are very valuable in urban design. You need visualization skills to imagine and depict alternative futures. As architects, we frequently go beyond an either/or situation and find new alternatives. The skills are important, but so is the mindset. I believe that architects are meliorists. We are convinced that we can build a better world and optimistic about actually doing so. Our role is a positive role, as opposed to professions where the roles are defensive or adversarial. We imagine possibilities beyond those that are evident in a given situation.

KC: But this process of changing the LA River may take a very long time.

AG: Before I launched my own practice, I was a principal designer in large firms designing large buildings. To get those structures built involved the coordination of many people working with very complex systems over a period of years. I learned to stay focused on an objective while going through a long process.

KC: What would you advise other architects wanting to get involved with a significant civic or political issue?

AG: Very specifically, if you are having a design charette, it is important to brief the design team ahead of time. Bring in people with serious expertise in particular aspects of the problem. With the LA River, the issues are always complicated because of overlapping jurisdictions, multiple regulations, a variety of property owners, and the frequent presence of toxic substances. There are rail lines, highways, and other urban infrastructure. In order to address sites along the river meaningfully, you have to have a pretty good briefing on flood protection, too. Every time we organize a charette, we put together sessions that may last a few hours or a full day, with briefings by the people who are involved on a daily basis with the issues.

KC: Have you influenced others?

AG: Not so much myself personally, but the LA River effort has. A whole group has sprung up around Ballona Creek, which drains West Los Angeles. This has been spearheaded by an architect, James Lamm, AIA. Jim says that he got into it by looking at what was going on with the LA River and saw the same opportunities over there.

KC: Are there other large-scale civic design issues that you are involved in?

AG: There is another huge issue in Los Angeles that has been in the back of my mind for a long time. It is the problem and the opportunity represented by the hundreds of miles of boulevards with underutilized retail frontage. These are not boulevards in the classical French sense of quadruple rows of trees with monuments at periodic intervals. Here, our boulevards are arterial streets spaced about a mile apart and commercially zoned along most of their length. The city, with its framework plan, laid out the idea that denser, urban, mixed-use development would be encouraged at transit and commercial nodes. But the plan has not addressed this huge inventory of boulevard frontage and what might be done with it.

We should address the potential of these major streets not as simple lines of movement, but as attractors of denser mixed-use development. In the process we could make boulevards that are worthy of the name. The issue here is that there is too much commercial zoning, which results in the underutilization. At the same time, we have a tremendous housing shortage in Los Angeles. These boulevard frontages could be rezoned residential with mixed use.

Recognizing that this city consists of a large number of single-family residential neighborhoods, it will be important that, if we densify the boulevards, we do not disrupt the fabric of the existing neighborhoods. If we are going to create a more sustainable city, we do need to densify, but we need to develop in ways that are humane and resource-efficient.

We are also one of the most “park poor” cities in the country. Rethinking the river, its tributaries, and its watershed is one way to address the lack of parks. The boulevards may be a way of addressing the housing crisis.

If you take the model of the river, we articulated the vision and then built the support. Support begins with a vision. Then one must build consensus. Consensus building is slow. You begin with a few people, but gradually you enlarge the field of involvement. The rivers and the boulevard corridors present extraordinary civic opportunities.

Interviewer Kenneth Caldwell is a communication consultant and writer based in Oakland, California.

Photo of Arthur Golding by Deborah Weintraub, AIA; aerial photo courtesy Arthur Golding; drawing of Chinatown Yard by Arthur Golding.

Originally published 2nd quarter 2002, in arcCA 02.2, “Citizen Architects.”