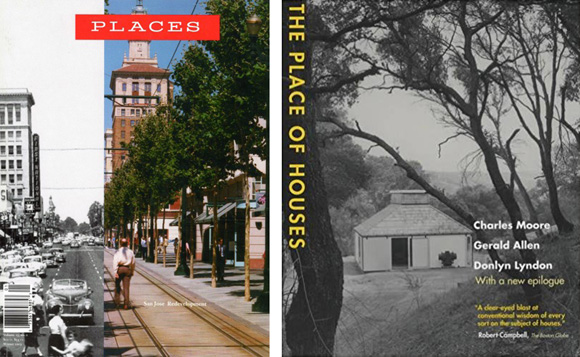

An architect, co-founder of a famous firm; an educator, long associated with Berkeley, MIT, and ILAUD, a renowned summer program on urban design; a writer whose just-published Sea Ranch monograph is an architect’s must-have; an editor whose journal Places transcends genres in a way that echoes his whole career—these are the achievements of a life that the AIA California Council recently honored. Meeting with Donlyn Lyndon at his house in Berkeley, I asked him to describe the thread that connects these different aspects of his remarkable career.

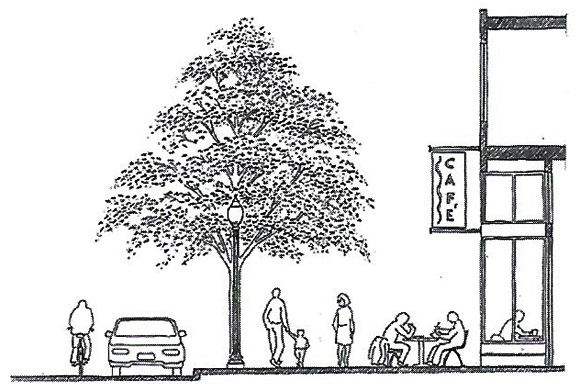

Lyndon: What motivates me is to show the ways that buildings can become something more than just individual projects—how they can be part of their larger environment, and contribute to it. My teaching aims to make people understand the richness of the experience that architecture can afford. I like that phrase. Architecture affords us the possibility of doing or experiencing things that aren’t otherwise available.

Lyndon attributes this impulse to a visit made as a teenager in the early fifties to “Design for Modern Living,” an exhibit at the Detroit Institute of Fine Arts, with model rooms designed and furnished by the Eames, Florence Knoll, George Nelson, and Jens Risom.

Lyndon: I was admiring George Nelson’s room. His wonderful bay window, with a platform and mattress in it, exists in almost every house I’ve ever done. Standing there, I started listening to what people were saying. They just couldn’t get it—they rejected the thing outright—and I thought, “I have to do something.” I could see how people closed themselves off from the riches of experience that modern architecture could afford. I wasn’t sure yet whether I was going to become a designer, or teach, or write about architecture. And I’ve never been able to make up my mind.

I asked Lyndon which one—designing, writing, or teaching—meant the most to him.

Lyndon: To make places that people actually can live with and enjoy, that will afford them a range of opportunities— things to look at, think about, and change—there’s a dimension to that which writing or teaching doesn’t have, although I love to write and to teach.

Lyndon has clearly been influenced by his partners and by like-minded architects like Joe Esherick. Are there others?

Lyndon: My father was a tremendous influence, although I took a very, very different path in the work that I’ve done and in the kind of architecture. My passion for it, my sense that it’s important, my belief that buildings can embody thought all stem from my experience with him, amplified by my education at Princeton and particularly by my contact with Charles Moore. Giancarlo de Carlo is an influence. My stepmother, Joyce Earley, a landscape architect and planner, made me understand landscape. “It should really be about environmental management” was her comment on Bill Wurster’s proposal to create a College of Environmental Design at Berkeley. “The landscape is alive.”

Turning to the Sea Ranch, the subject of his and Jim Alinder’s Princeton Architectural Press monograph, Lyndon’s starting point was how its landscape has changed.

Lyndon: Larry Halprin planted a huge number of trees, thinking that half of them would die. Instead, they propagated. When you go to the lodge now, you can’t see the condominium, because all this vegetation brackets it off. The same is true of Esherick’s hedgerow houses. You can’t even find the hedgerow, and you can hardly find the houses. Both of these projects were meant to be examples of how to build on the site, but their gestures to the landscape don’t exist anymore. You can’t see them.

Does he consider the Sea Ranch a viable model of urbane development in a rural context? If he were to do it again, would he do anything differently?

Lyndon: That word “urbane” is the twister, because the Sea Ranch has a lot of residual suburban impulses. It needs a center, for example. Gualala provides one, but you have to drive almost eight miles to get there. And the architecture tends to discard the street. It focuses on the meadow, the ocean, or the trees, and pretends that the street isn’t there. Yet that’s where the primary social encounter tends to be, so a more appropriate model would recognize it as a place of social engagement. Also, everyone’s mantra about the Sea Ranch is “living lightly on the land.” I suggest in the book that we ought to modify this. Others built on the land before we got there. It wasn’t a wilderness. We’re part of it, and “living lightly with the land” seems to incorporate this better.

Does a lifetime achievement award stop Lyndon in his tracks or prod him to keep going?

Lyndon: I’m looking forward to designing two new houses at the Sea Ranch, completing a cluster of four that includes my own house and another I designed for my brother. I’ll continue with Places, which now has new sponsors and opportunities. I’m planning two books—one on Giancarlo de Carlo’s influence on America and America’s influence on him; and the other drawing on the thousands of slides I’ve taken, each making a different point about cities or architecture, in order to construct a set of observations. Then finally I’d like to do a monograph that brings together in one place my writing, my lectures, and my work. It will be a chance for me to develop the thread that you were asking me about.

Interviewer John Parman is the co-chair of AIA San Francisco’s _line and a founder of Design Book Review. He also edits Dialogue, Gensler’s twice-yearly client magazine.

Originally published 3rd quarter 2004 in arcCA 04.3, “Photo Finish.”