California is an imagined canvas upon which people paint their desired futures, but those futures are never as easy to attain as we think or hope. As an architect, I am reminded of the way people perceive a beautiful house, compared to the way the architect and the builder see it. The casual observer might revere the design and the craftsmanship but will know little of the arduous process involved. They see a finished object, a result. Those who were involved more deeply at each step still hear the echo of problems and constraints that had to be overcome. Looking at the perfect corner on the window trim still reminds them of the day the carpenter was throwing his tools.

I have lived in California for 40 years. It has been a long, complicated affair, and I am still in love, even after unexpected struggles and perhaps more so because of them. California was the emblematic dream destination to a teenager from Philadelphia. It was a place of vast sunny landscapes and connections to nature, especially for those of us who came from more industrial, grayer places. It seemed like the best music and the coolest ideas originated there. It was the far away place, across the horizon, over the rainbow, where the grass was always greener.

I ran this by two architect friends who are also from back east, to see what lingered for them. I asked for their snapshot of what they found important about the state. The first friend, who pursued an academic career, described the cross-fertilization of environmentalism and planning, the experiments in lifestyle and the American Frontier that attracted European artists and intellectuals. He sent me a photo of an iconic William Wurster house on the beach in Aptos and links to some websites about the Case Study Houses and Julia Morgan. The other friend, who designs a lot of restaurants, answered with a one-word text, “Avocados.” It was tongue in cheek, but it captured something primal about the climate, sunshine, and earthiness here.

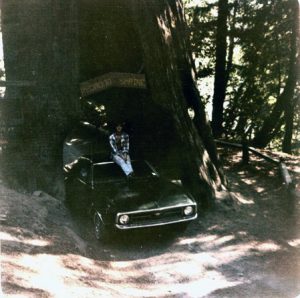

The visceral appeal of the avocados and the attraction inherent in the American Frontier made me reflect more on why California matters to me personally. It started with escape. When I was seventeen, I needed to go somewhere, and the somewhere needed to be far away. It had to be a major journey. That summer I drove out west to check out California. My older sister joined me. She was ready to get away, too.

I bought an old Mustang with money earned from painting houses and doing odd jobs. Few things are more cliché than buying a Mustang to drive to California, but in this case the car was bad enough that the veneer of cliché gave way quickly to the uncertainty of whether the motor would start. At the end of each day I had to park the car facing downhill, so I could roll it and pop the clutch, to get the engine fired up. I did this on city streets and the grassy slopes of campgrounds. If there was no slope, we had to push the car, then I’d jump in. So we limped our way westward in a tainted Mustang, the first big defect in the California fantasy.

The clutch-popping workaround kept us going, except for the time the rear axle came loose on the freeway and the wheel pulled free from the car, dropping the rear end to the pavement at 60 mph in a plume of sparks. We pulled over, jumped out, and ran down the embankment. My sister deadpanned, “Do you think it’s gonna blow?” We were in Nebraska, standing in a corn field, looking up at a dead car. California was still a long way in the distance. Eventually a tow truck driver rescued us. As we crowded into the cab of his truck, he told me not to worry, it was just metal. We spent the night in town and by the following day the car was back on the road. The tow truck guy was also the town mechanic, and he had tracked down replacement parts for us at a salvage yard. Cars and people were different then. The cars always broke down and everyone collected and exchanged parts to help each other get back on their way to wherever they were going. The experience opened my eyes to the value of community and the kindness of strangers.

We made it out west, and California, particularly the San Francisco Bay Area, was as enticing as I had hoped. The light was different. The houses had large expanses of glass, and there were great outdoor spaces. Landscape design seemed as important as the design of the buildings nearby. The Bay was felt everywhere. The Golden Gate Bridge was the perfect balance of grace and strength, one of the best advertisements for design I had ever seen. The homes were perched on hillsides, gazing out to the ocean, simultaneously precarious and confident. It all felt so optimistic and promising.

We returned to Pennsylvania, but I was changed. I knew I needed to move out west for real, not just visit. Between the trip and much lobbying from my mother, who was both an interior designer enamored with modern west coast design and a rebel intrigued by alternative lifestyles, I decided to apply to study architecture at UC Berkeley. I was accepted, but I needed another year to get ready. I asked for an extension and learned that they were not offered. But I was assured that, with my qualifications, I would easily be accepted again the following year. So I prepared to hit the road again, on a one-way journey, to get a foothold in the state.

The Mustang, which now had a new alternator and battery so it would actually start, took me as far as I could drive without drowning in the Pacific Ocean. Along the way, I stayed with relatives I barely knew and slept in the parking lots of truck stops. I didn’t stop until I was at Land’s End in San Francisco, watching the waves at sunset, with Bruce Springsteen wailing on the car stereo. At night I slept on a couch in a studio apartment in a poor neighborhood. Trash fires were set every Saturday night in the projects across the street, just for the thrill of watching the fire department respond with a fleet of trucks. During the day, I climbed scaffolding and painted Victorians, using the trunk of the Mustang as my toolbox.

It is deceptively easy to write about all of this now, but it was deeply worrisome at the time. I was concerned about how I could ever save enough money or get ahead. The guy I rented the couch from, a cousin I had never met, was older and struggling to find work. He had the qualifications to get a job as a paralegal. He sent out eighty resumes and received zero replies. He was stunned. I was stunned. He slept in the closet of the apartment, on a thick piece of foam, so he could rent out the couch to make ends meet.

Then I got the rejection letter from UC Berkeley. My acceptance the previous year, and their assurance that I would be reaccepted, had been the cornerstone of my plan to move across the country to start a new life. Now that stone had shifted off its foundation and threatened to bring down my imagined future. Trying to maintain my momentum, I moved from San Francisco to Berkeley, to be closer to the University. Due to a tight market for student housing, that amounted to renting a dining room in a house with three bedrooms, already filled by three students. I hung blankets in the doorways for privacy and painted a mural on the wall, showing the Golden Gate Bridge and the hills of the Marin Headlands. The mural was my cave painting, illuminating my sleeping chamber with elements of my world that loomed large and required tribute to ensure my survival.

At UC Berkeley, I was met with polite suggestions from the admissions department that I consider one of the other campuses in the UC system, the ones with “more favorable admissions demographics” or, as we said on the street, “the party schools.” After several visits to the admissions office to plead my case, there was a breakthrough. A thoughtful employee at the counter pulled my paper file to investigate the specifics. The folder was empty. Suddenly we both knew why my qualifications were not up to Berkeley’s standards. They were non-existent. My re-application had not been linked to my original application. My documents were languishing in the basement. Once those files were brought upstairs and reviewed, I received the letter that starts with “Congratulations” and you don’t even need to read the rest. The dream was alive again, though it was less fantasy and more hard work. In that struggle, however, UC Berkeley taught me an essential lesson about life and dreams, before I even set foot in a classroom. It was my first confrontation with a major bureaucracy that said “no” far more readily than “yes” and had little regard for my value or intentions. I had to be resourceful and persistent in order to prevail.

The University went on to be one of the best opportunities in my life. My eyes were opened to architecture and photography and the hard work that both required. Critical thinking and opportunity were abundant. I met inspiring people who challenged my assumptions. I put down roots that have deepened and sustained me ever since. As I write this, I am sitting in a house in the Oakland Hills with a view of the Golden Gate Bridge that is not so different from the one I painted on that dining room wall in Berkeley.

I often take comfort in the phrase, “The trouble with opportunity is that it usually comes disguised as hard work.” In this case, the word “opportunity” could be replaced with “California,” and the guidance would be more applicable to my journey. Rolling a dead car down the hill each morning, living on a couch, watching a guy live inside a closet in San Francisco, living in a dining room in Berkeley, and being rejected by UC Berkeley were confusing welcomes to California, partly open arms and partly gut punches. But they were ultimately a gift.

The lessons have proven invaluable for my architecture career. Design is a process of solving difficult puzzles to achieve elegant results. Negotiating code requirements, neighborhood concerns, and client aspirations requires skills similar to those that helped me cross the country and make a life in California. The long drive was worth it.

Author Kurt Lavenson is principal of Lavenson Design in Oakland. He migrated from Pennsylvania to California in the late 1970s and worked in the trades while studying architecture and photography. After discovering that he preferred construction sites to working inside an architect’s office, he spent the next fifteen years as a designer/ builder. He currently operates a solo architecture practice where he blends design principles, psychological insight, and a touch of alchemy in the quest to create great residential spaces.

From arcCA DIGEST Season 07, “Concerning California.”