The focus of the 2nd quarter 2009 issue of arcCA, “Design for Aging,” is on concrete examples that represent existing and emerging models for building. Yet the issue of designing for aging—of being designers for aging—calls on us to consider other, maybe deeper but certainly more widely diffused questions: questions of empathy and difference, of identity and memory, of dwelling and duration.

The Allman Brothers Band at Fillmore East (clearly the finest concert album in the history of rock-and-roll) is one of the fond emblems of my youth. One of the boys in the dorm room across the hall from mine during my not-untraumatic sophomore year at boarding school played it constantly, and “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed” offered solace for the tribulated teenager. I was fourteen, and I’m fifty-two now, and in some ways I’ve matured. In others, not so much. But I now recognize something that I couldn’t have predicted then: just how much the fifty-two-year-old me shares the identity of the fourteen-year-old me. At that time, I could not conceive that the fifty-two-year olds among my teachers could possibly have had any relation to any fourteen-year-olds who had ever lived.

Adolescence is a time for asserting one’s difference from one’s elders, but it may also represent a deeper characteristic—I would say flaw—of us humans, which is our tendency to define ourselves by way of differences from others.

I was chatting with a younger colleague recently about an idea I had for an online service that would help you plan an architectural tour for your vacation. He thought it interesting but said it illustrated a difference between our generations: his generation would just start out on the vacation without planning ahead. I suggested that this wasn’t a generational difference, it was an age difference: when I was twenty-three, I didn’t plan my itinerary, either. There’s been a lot of talk lately about generational differences—what Gen Xers want out of their work life, as compared with Boomers—and we even had an issue of arcCA on “The ‘90s Generation,” but I’m skeptical.

We like to assign categorical differences between ourselves and others, perhaps because they appear to absolve us. It is extraordinary to me—this is a confession—how instantaneously I identify a difference between myself and the idiot who cuts me off at the intersection. Skin and hair color are among the easier differences to grasp, but any difference will do; if I can’t spot a visible one, “idiot” will have to suffice. I’m an equal opportunity bigot when it comes to distancing myself from someone who’s done something I would like to think I not only wouldn’t do, but couldn’t do—because I’m essentially not like that person. And being not like some miscreant is simpler than being virtuous myself. It’s easier to define oneself by what one is not.

“Look where you’re going, old man! (I’m glad I’m not like you.)”

But I am like him and at the same time like the fourteen-year-old enjoying Duane Allman’s guitar. I’m like the person I’ve been and the person I will be, more than not. I’m not some other category of person altogether, nor are they.

While it may be difficult to resist thinking of people as categorically different, it is at least a readily understood problem. It intersects, with heightened intensity when we design for aging, with another, much less simple problem: how to comprehend time in architecture.

In All the King’s Men, Robert Penn Warren’s narrator remarks, “Time is nothing to a hog, or to History, either.” It is something only to people. Awareness of “time past and passing and to come” is our unique burden, and it is as much a well of anxiety as of opportunity.

Buildings are among the most long-lasting things we make, and philosopher and architectural historian Karsten Harries has written compellingly of the yearning for immortality that underlies monumental architecture—perhaps all architecture. For us mortals—beings who not only die, but know we die—there is comfort in endurance.

Yet duration is fraught with difficulties. The practical ones can be overcome with better sealants. The conceptual ones are tougher. While people in general value the continuity of old buildings, we suffer the professional hazard of abstracting historic structures as references and artifacts, rather than ongoing places of life.

We seek the new, insisting that buildings appear “of their time.” But how long is “their time”? And when did it begin? How much of the newness we produce is formed of positive discoveries and beneficent syntheses, and how much is the anxious assertion of not-oldness?

Our search for the ever new may not always be our most gracious offering to people who have dwelt a long time in the already existing world. What is the best relationship between making an architecture of the moment and understanding people who are older than us? Can we understand their moments as our moments?

What, in fact, do we mean by “dwelling”? Heidegger aside, to dwell on something means to consider it at length—for a long time; and to dwell in a place has similar implications. (Staying in a motel for the weekend is not dwelling.)

How does time reside in architecture? (Perhaps the greatest failure of American postmodernism was its insistence on irony, which has a far shorter effective time span than do buildings.)

How does time reside in the mind of the architect? (The thought-time of the pencil, for example, compared with that of Revit?)

In the experience of practice? (Colin St John Wilson referred to his design of the new British Library, begun in the 1960s and completed in 1997, as his “Thirty Years War.”)

Of construction? (Surely the time-sense of the mason is distinct from that of the steelworker.)

These questions offer grist for the mill, if little guidance. I hope my starting point, at least, is clear: my love of The Allman Brothers Band at Fillmore East is not nostalgia; it is as much a part of my current identity as is my iPhone. I am somewhere between young and old—as are we all—and there are times when the gulfs between these ages and mine seem unbridgeable. I would that architecture were more often thought of as a bridge between ages—a continuer, not a segmenter, of time.

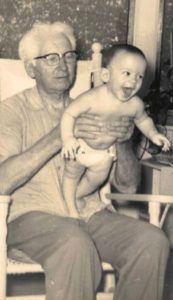

Author Tim Culvahouse, FAIA, is the editor of arcCA. In the sepia photo, he is in his grandfather’s good hands.

Originally published 2nd quarter 2009, in arcCA 09.2, “Design for Aging.”