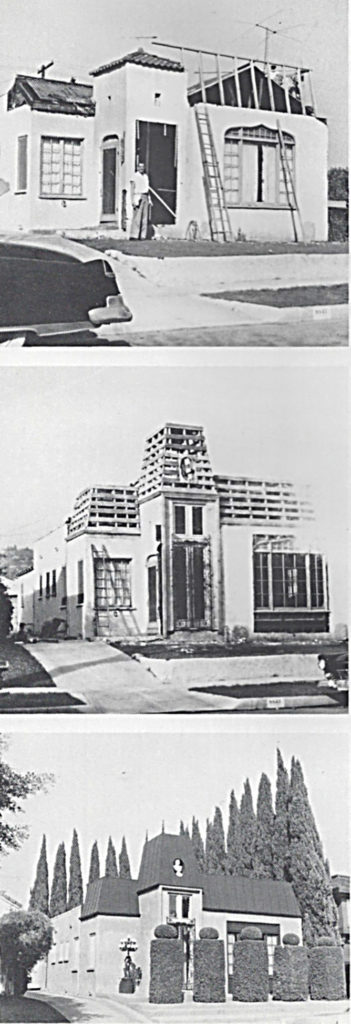

In Exterior Decoration: Hollywood’s Inside-out Houses (Los Angeles: Hennessey & Ingalls, Inc., 1982), John Leighton Chase scrutinized and elevated the remodeled bungalows of West Hollywood, the transformation, as he puts it, of “Spanish Colonial Revival mutts into French mansarded pedigreed poodles.” In the process, he notes,

The little bungalows became inside-out interiors. Urns and finials were placed on rooftops like bibelots on a fireplace mantel. Blank windows and panels of wall trellis were arranged in compositions as though they were pictures hung on a living-room wall.

Exterior Decoration offers a rich catalog of such details, but it is as much a sociological study as a formal one.

There are certain sectors of Los Angeles, and certain sectors of Los Angeles society, that occupy the front line in the battle for status identity and dream realization. The entertainment industry, the trade of interior decoration, and the gay subculture are among the groups especially concerned with appearance, self-image, and social roles.

These concerns are also of paramount importance in the West Hollywood neighborhood of Los Angeles, an area associated with all three of these groups.

But, Chase cautions, we should be careful not to take too narrow a view of the remodelers or too shallow a view of their goals:

The West Hollywood remodels have sometimes been regarded as the anarchic wit of a largely gay community of interior decorators. But the houses are not intended to be jokes. The remodels have more to do with anxieties produced by Los Angeles’s loose social structure than with a taste for camp. Except for a few truly idiosyncratic buildings, the remodels reflect the desire to lay claim to upper-class status.

Chase’s method for identifying the subjects of his book mirrors that of the remodelers themselves: driving the streets of West Hollywood. “Only after seeing what buildings were out there, what the raw material was like, did I want to begin sorting through it and discovering the buildings’ dates, owners, and designers.” Once having identified them, he digs deeply, tracing development patterns, the formative pressure of financial constraints, moments of invention and lineages of reproduction, and swings in popular taste.

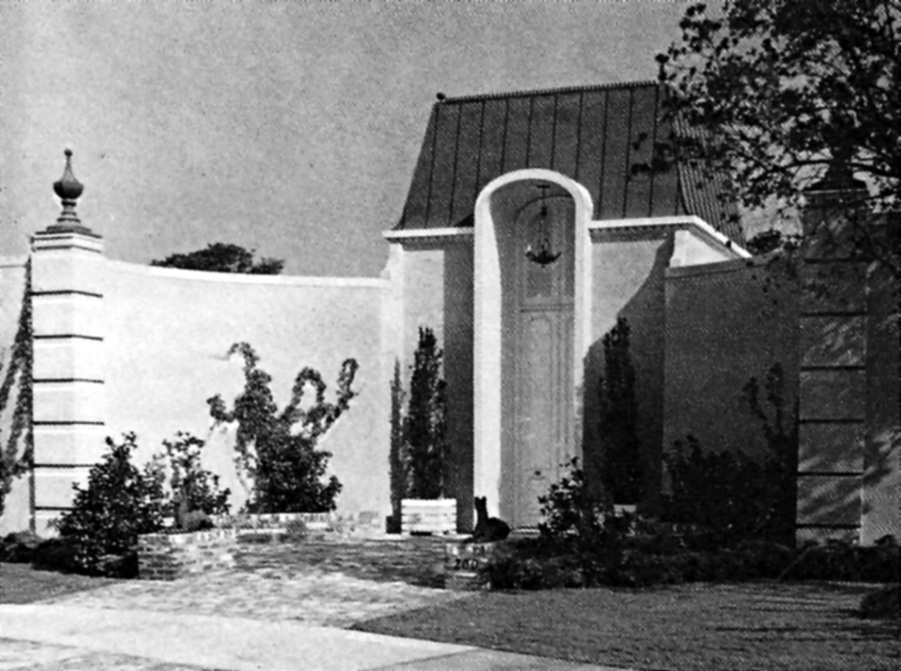

Among the most influential figures in the West Hollywood remodelers’ universe were the team of Reg Allen and Jack Stevens, who introduced “the use of a nailed-on mansard roof to transform a nondescript cottage into an aspiring townhouse”; and architect John Woolf, inventor of the “Pullman door,” a “tall, arched door penetrating the roofline, which has become such a popular expression of upper-middle-class aspiration in Los Angeles.”

The Woolf arch had wide appeal in Southern California because it is an emphatic punctuation mark, it is theatrical, and its height makes it appear forbidding. The door fit the spirit of Edith Wharton’s aphorism that “the main purpose of a door is to admit; its secondary purpose is to exclude.”

Such motifs made possible dramatic visual transformations on minuscule budgets. Structural and spatial transformations tended to be modest, mostly confined to the removal of an interior partition or two to create larger but fewer spaces for what were typically households without children.

This opening up of the plan was characteristically modern, as was the connection between private indoor and outdoor space at the rear of the house. The tension between modernization and historicism is a thread running through Exterior Decoration, as it runs through the Hollywood Regency, the most recognized style of the period, “concocted by mixing modern and historically inspired elements with quintessential Southern California nonchalance.”

The Hollywood Regency style was theatrical, its walls exaggeratedly blank or its columns impossibly thin . . . . The detailing . . . often had a flattened, two-dimensional quality, in order to match the sleekness of the wall surfaces. Hollywood Regency was the perfect architecture to represent the Hollywood that had brought [in the words of William C. DeMille] “a world of silken underwear, exotic surroundings, and moral plasticity” to the United States, through the medium of film.

In the concluding chapter of Exterior Decoration, “The Mind of the Decorator and the Concept of the Remodeled House,” Chase makes explicit the commonly understood divergence between the decorator and the architect.

The West Hollywood remodels are vulnerable [to satirization], for the reason that their designers were simply more willing than their architectural counterparts to reconsider the values conventionally assigned to the elements in their respective vocabularies of design. Modern for decorators has historically been a style, and not the religion it has been for some architects.

Unlike the architect, the decorator supplies both advice and merchandise, so “aesthetic principles are bound up with salesmanship.” The decorator “caters to the market, to fashion, and to the need to relieve boredom much more than architects generally do.” Like set designers, their work is economical and ephemeral. And yet,

. . . for all the expediency exhibited in the West Hollywood remodels, they nonetheless have a message. The systems of meaning found in them convey a lot of information in a few details. Architects who pay little attention to these conventions might improve their own skills at communicating with the users of their own buildings by studying the remodels.

From arcCA DIGEST Season 10, “Other Beauty.”