Fargo

Forty years ago, I left my home town, a small grid city of about 40,000 occupying six square miles, with a bustling downtown bounded by the Northern Pacific and Great Northern Railroads. It’s the place Duke Ellington made his great recording, “Fargo, ND, November 7, 1940.” Today it is a sprawling, formless suburban town about twice the population and six times the land area I knew, with a dead, depressed, deteriorating center. No evil empire could have destroyed the civic community life more successfully than was achieved here.

Maybe that’s what happened in Fargo.

Rome

Fifteen years after leaving Fargo, I lived and worked for two years in central Rome, still a beautiful, functional and environmental model of cities of the past, a model we have abandoned, without a replacement, over the last century. There, I experienced the most phenomenal street life on earth. I was told that all businesses except UPIM, the largest department store, were owner-operated. A cohesive culture certainly helped to create that street life. But I also believe that the street life helped create and sustain the culture.

San Francisco

For most of the past twenty-five years, I have lived in San Francisco, whose pattern of neighborhood commercial districts, each serving an area of roughly a half square mile, is the basis for its ongoing magic. The typical pattern of through streets parallel and adjacent to slow neighborhood commercial streets distinguishes SF neighborhoods from those of Oakland and Berkeley, whose commercial streets are clogged with through traffic.

Looking Outward from Urban Design

I have been an urban designer over the past twenty- five years. I’m convinced I am an amateur, as I increasingly believe nearly all of us are amateurs—professional architects, engineers, economists, planners and urban designers—too busy and too narrowly focused to realize the impact of our work on the whole of complex urban life. Each of us tries to do good and responsible work on individual projects, only to see the aggregate results produce the ugliest and most damaging urban development imaginable. Focusing on our immediate projects, we disregard the larger world we leave to our heirs, a fragmented world in which ever-increasing population and per-capita consumption bump up against global limits.

While we can protect wetlands or create more pleasant, economically stratified small towns, it is only in Healthy Cities that we can experience the breadth of our increasingly plural culture, feel what we have in common, and, perhaps most importantly, develop the broad cultural intelligence to respond productively to our deteriorating social and environmental state.

Principles of Healthy Cities

In her study of the nature of vibrant social and economic urban life, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs notes that cities are not small towns grown large. The planning principles of small towns assume that residents know their neighbors, while cities are, by definition, full of strangers, even at one’s doorstep. The bedrock attribute of a successful city district is that a person feel safe and secure among these strangers. Accordingly, safe streets require eyes on the street and generally continuous sidewalk use. Other necessary conditions for the successful city identified by Jacobs include: a fine-grained mix of primary uses, small blocks, aged buildings (for economic variety) and density. She views cities as hives of trade and innovation, ever changing in response to their context. She describes the complex systems-planning appropriate to ongoing growth and change. In this and subsequent books, she describes the economic relationships between cities and their rural, national and global contexts. The picture is one of cities as bustling organic entities with enough energy and intelligence to offer residents full and rich lives while responding capably and collectively to our economic, social and environmental contexts.2

The cities described by Jacobs and the examples provided by beautiful cities of the past, such as Rome, can lead toward a new model of Healthy Cities that are singularly suited to realize complex community, including support and encouragement of:

-

- broad individual experience and the opportunity to live as one chooses, to participate in the local economy and to help create the physical environment;

- complex webs of community among an increasingly plural population;

- greater cultural awareness and aggregate intelligence; and

- growth of a more restorative economy and a more sustainable culture.

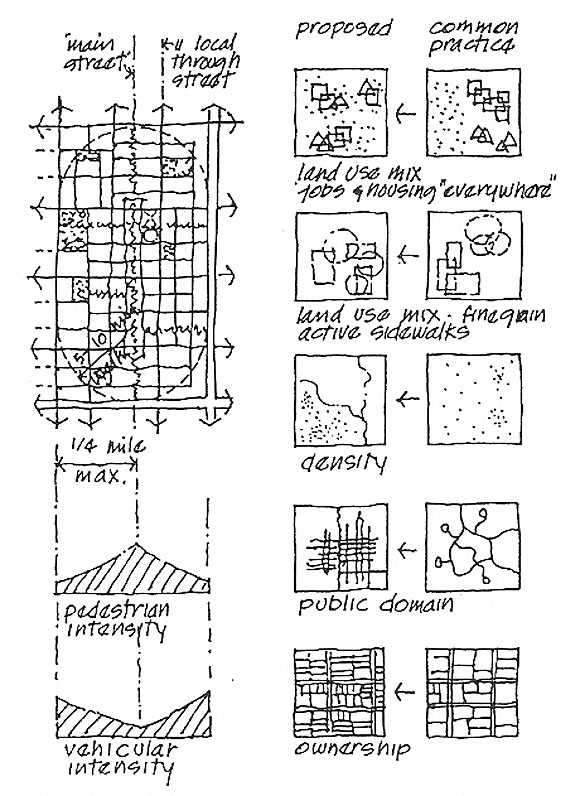

Three principles quantify Jacobs’s observations and establish Pedestrian Precincts as the basic units that describe the general texture of Healthy Cities:

-

- community services are dispersed throughout the city, within the limits of their catchment population requirements, and are located to maximize eyes on the street;

- density is sufficient to activate the sidewalks, but high densities are limited to assure small-scale development opportunities and variety in housing types; and

- office and residential uses are mixed to encourage continuous sidewalk use day and night.

Pedestrian Precincts do for cities what Pedestrian Pockets do for suburbia: encourage the design of particular places with a fine-grained land use mix, an active and healthy public domain where pedestrian and transit circulation are used for a majority of daily trips, a revived sense of community and more sustainable living.4 With a population between 8,000 and 20,000, an average residential density of at least thirty units per net acre and an equivalent concentration of other community facilities, including most employment, Pedestrian Precincts support the full range of services necessary to affordable, dignified living—jobs, schools, health care, shopping, entertainment, recreation and civic and religious activities—all within walking distance of every resident.

Planning our cities over the coming decades will be, in large measure, a systems problem of understanding the full consequences of any development on the balance of the community, insuring that each step leads to more sustainable and humane life and communicating these views, clearly and simply, to city residents and their representatives. By allowing evaluation of the aggregate built environment at a manageable scale, Pedestrian Precincts may become the most useful governmental entities for the evolution of Healthy Cities.

Community: Larger Life, Justice and a Restorative Economy

“When it is said that we are too much occupied with the means of living to live, I answer that the chief worth of civilization is just that it makes the means of living more complex; that it calls for great and combined intellectual efforts, instead of simple, uncoordinated ones, in order that the crowd may be fed and clothed and housed and moved from place to place. Because more complex and intense intellectual efforts mean a fuller and richer life. They mean more life.” —Oliver Wendell Holmes, from the prologue to The Death and Life of Great American Cities

The life of a greater whole can be felt in closely knit groups of all kinds—a relationship between two people, small enthusiastic businesses, jazz groups, political activist groups, sports teams, church congregations—any group in which openness, enthusiasm and common cause exist among its members. Such groups exhibit intelligence, artistic expression, awareness, strength of purpose and power beyond that of their individual members. The individual genius pales by comparison with, for example, the everyday crafts culture that supported Borromini and produced the windows, storm sewer covers, paving patterns and stone and plaster work that grace Baroque Rome’s streets. The instincts, senses and vulnerability that allow each of us to connect enthusiastically to various forms of larger community can be among the most powerful of life’s forces and can change our perceptions of who we are.

In The Republic, Plato describes a concept of ideal democratic life in which culture is the result of a just and civil society. In a civil society, each person acknowledges the differences among all citizens and supports concepts of justice. In a just society, each individual’s distinct aptitudes and capabilities are reflected in their unique associations and connections, creating a dense web of overlapping community networks.

As an integral part of a just society, a restorative economy can be a facet of whole life—the response of complex community to growing environ- mental deterioration.5 Our unique capacity to dominate and manipulate other forms of life leaves the environmental balance necessary for civilization’s survival wholly in human hands. Sustainable civilization and its relationship with the environment may be compared to an acrobat on a high wire, maintaining balance while moving from one position of instability to another. Like the acrobat, sustainable culture would be fully alive and attentive to the moment, capable of immediately sensing and communicating imbalances to other parts of the system and responding in its own best interest. Unlike the acrobat, how- ever, the civilization could not muster all necessary knowledge in advance, and so would often have to learn as it acts, through incremental, direct experience.6

Cities, with their potential to support complex community and larger cultural life, offer us—through strong, public, guardian values7— our best, perhaps our only opportunity to transform our pre- sent economy to a progressively more restorative one. The economies of cities, comprised of thou- sands of businesses, both large and small, cooperating, competing, coalescing and adapting to their ever-changing contexts, offer an enormously complex resource. They can transform the ways we conceive, produce, use and reuse the hundreds of thousands of products and services we have come to expect in everyday life. They can provide a business setting where “doing good is like falling off a log, where the natural, everyday acts of work and life accumulate into a better world as a matter of course, not a matter of conscious altruism.”^8 Cities can create an economy that is supportive of ongoing life, an economy that is more particular, just, civil, intricate, comprehensive and diversified than today’s, with a broader range of people involved, more kinds of work and more locally generated control and wealth.

Cities have been the spawning ground for the development of economic life and broad culture throughout the history of our civilization. They contain the seeds of their own regeneration. Large cities supportive of justice and civility, with their potential for greater intelligence and community, offer us our best opportunity to respond to the growing pressures of population growth, a plural society and a deteriorating environment. While present efforts on behalf of our natural environment are important, the growing crisis we face is in large part due to our isolation and ignorance: a crisis of community.

For a more humane and sustainable civilization, we first need Healthy Cities.

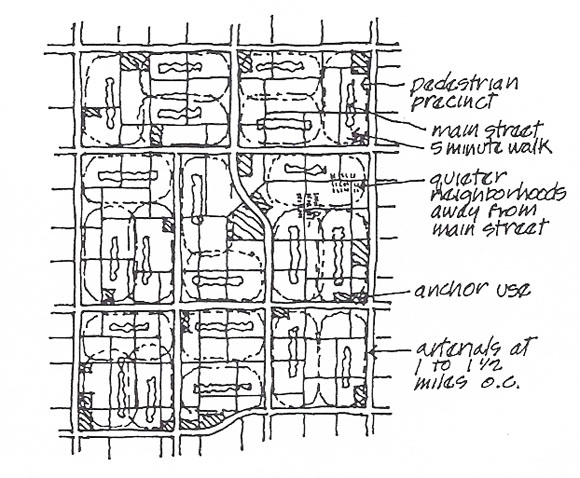

Planning Principles

With a size of 130 to 320 acres, Pedestrian Precincts allow pedestrian and local transit access on a fine-grained street grid. Streets and neighborhoods are varied in character, with a broad range of house types. Significant small parcel development promotes home ownership and resident investment in business property. A majority of the city’s jobs occurs in these Precincts. Concentration of community services near the center of the Precinct, along a pedestrian-dominant, sunny Main Street, provides a high intensity of social connections; a parallel and adjacent local through-street accommodates service, auto-oriented businesses, parking access and bus and light rail routes.

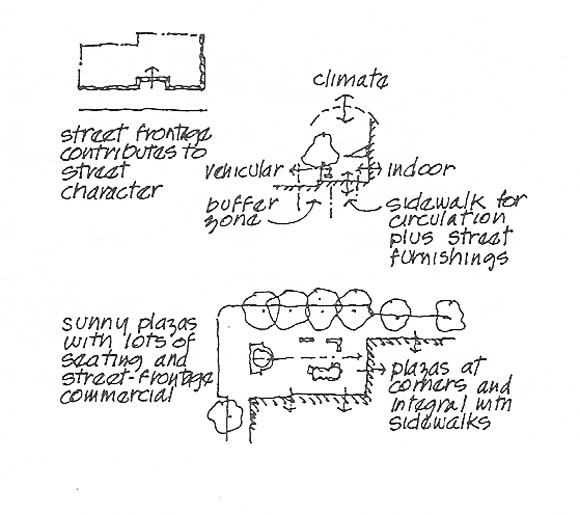

Streets are the primary images of a city and, with plazas and small parks, should be coherent urban spaces, formed by the buildings defining their edges. In addition to accommodating complementary pedestrian and vehicular circulation, these positive urban spaces should be simple and visually dominant enough to accommodate substantial variation in individual building design, hard and soft landscaping and street furnishings.3

Active sidewalk life requires a delicate mix of land uses. 80- 90% of the total building area of a Pedestrian Precinct is likely to be residential, 5-15% office and only about 5% commercial and community uses that contribute directly to safe and active street life. Assuming three- and four-story average building heights, commercial and community uses will form up to 20% of the total street frontage. Businesses which are open at night, increase sidewalk activity and keep eyes on the street—restaurants, cafes, bars, convenience stores, video stores, health clubs, galleries, self-service laundries, book- stores and the like—are best located at corners and at mid- block, offering pedestrian safe-havens every 150 feet or so. Office and residential lobbies should be at street level. The floors of residential units should be high enough above side- walk level for residents to feel comfortable keeping their windows open to the street.

The higher the intensity of development, the better the opportunities for active street life. Thirty residential units per net acre (net floor area ratio (FAR) of 0.6, with a resident population of 8,000 per square mile) is about the minimum density that can support active sidewalk use; it is close to the density of Berkeley. Eighty units per net acre (net FAR of 1.4 with a resident population of 24,000 per square mile) is the approximate maximum density to allow significant individual choice of housing types. Some San Francisco neighborhoods have densities up to seventy units per net acre, comprised of a mix of duplexes, flats, three-story apartments over structured parking and some mid-rise apartments.

Healthy City Fabric results from meshing Pedestrian Precincts with citywide circulation systems and a spread of anchor uses. This is the general land use pattern of Siena, central Rome and Paris, and it would be the pattern of San Francisco if the existing downtown were spread among its 41 neighborhood commercial areas. Conversely, introducing large quantities of housing into our existing downtowns would provide new life around the clock and would offer a welcome addition to our choices of where and how we wish to live.

City arterial streets on a grid of approximately one to one-and-a-half miles are sufficient to distribute traffic evenly and to abut Pedestrian Precincts. Citywide transit systems with one or more transit stops at each Pedestrian Precinct allow for cross-platform transfer with local transit systems. The resulting circulation system allows for differentiation and coordination of local and citywide forms of transport.

Anchor uses are those with a citywide catchment population, heavy traffic requirements and special physical planning requirements—a university, business park, symphony hall, hospital, conference center, major hotel or sports facility, historic district or large-scale natural feature. Anchor uses are typically the “jewels” of the city, generating high levels of urban activity. They should be spread throughout the city, be directly accessible from city through-streets and be near both transit nodes and the Pedestrian Precinct’s Main Street. Each anchor use is capable of stimulating neighborhood economic, cultural and social life and can strongly influence local design character.

(In San Francisco’s Civic Center, anchor uses—city hall, opera house, symphony hall, central library, state office building, museum and convention center—are concentrated, rather than dispersed throughout the city, diminishing the potential for economic and social synergy. Paris, in contrast, has spread its cultural anchors throughout its arrondisements to maximize the economic and cultural impact of these special uses.)

Healthy Cities may be viewed as organic wholes with a variety of physical forms, living in an ongoing balancing act with their particular context. In Healthy Cities, each constituent part contributes to the health of a larger whole: the building contributes to the street, the street to the neighborhood, the neighborhood to the Precinct, the Precinct to the city and the city to its regional and global context. Conversely, concepts of justice, community and whole life imply opportunities for individual expression in the physical environment, leading to the need for each whole to encourage variety among its constituent parts, with each level of organization represented in the public governance structure.

- Charles Correa, Hon. FAIA, The New Landscape (London: Mimar, 1989), p. 83.

- Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (NY: Vintage Books, 1961), The Economy of Cities (NY: Vintage Books, 1970), Cities and the Wealth of Nations (NY: Vintage Books, 1985) and Systems of Survival (NY: Vintage Books, 1992).

- For elaboration, see Allan B. Jacobs, Great Streets (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993); William H. Whyte, The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces (Washington: Conservation Foundation, 1980); Donald Appleyard, Livable Streets (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1981); and Christopher Alexander, Sara Ishikawa and Murray Silverstein, A Pattern Language (NY: Oxford Univ. Press, 1977).

- Doug Kelbaugh, FAIA, editor, The Pedestrian Pocket Book (NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 1988).

- Donella H. Meadows, Dennis L. Meadows and Jorgen Randers, Beyond the Limits (Post Mills, VT: Chelsea Green, 1992).

- Gregory Bateson, Steps to an Ecology of Mind (San Francisco: Chandler Publishing, 1972), p. 498.

- Plato, The Republic, and Jacobs, Systems of Survival.

- Paul Hawken, The Ecology of Commerce (NY: Harper Collins, 1993), p. 14.

Author Larry Dodge, a sole practitioner in Piedmont, California, is an urban designer and architect who has worked on projects in sixteen countries.

Header photo illustration by Bob Aufuldish. Drawings by the author.

Originally published late 2000, in arcCA 00.2, “Common Ground.”