I’ve been asked often this year what new advances we can expect for housing in the next millennium. As housing shortages increase, as costs rise and the disparity between price and income widens, people want to know the way out of this intractable problem. I’ve maintained that lowering the cost of construction through factory production of units, or by minimizing the size of dwellings, or by stripping the architecture of all embellishments will not have a significant impact on housing costs to the occupant, and will certainly have a detrimental effect on the quality of housing and neighborhoods.1 The harsh lessons of public housing in the last millennium provide plenty of proof for that.

Amenity, Density, Community

For the thirty years I’ve been building, teaching, and writing about housing, I have reiterated that a primary goal is to provide the amenities of the single family house at increasing densities. The traditional detached house continues to be the mainstay of the industry, despite the fact that it is inefficient in terms of land and resource use, it is expensive, and its proliferation throughout the countryside increases commutes and the concomitant environmental degradation. Yet it continues to be the favored dwelling form, even though the nuclear family for which it was intended is no longer the dominant household type. If we can increase density with an acceptable housing form and with amenities comparable to the detached house, greater affordability and acceptability will be achieved. Certainly this will have a positive impact on suburban sprawl. But what about cities?

As households have changed, diverse types of dwellings, mostly in cities, have evolved. We now see specialized housing for people with various illnesses and disabilities (AIDS housing and congregate care for seniors), those with extremely limited means (shelters), and young professionals with high salaries (lofts and live-work). These trends are generally positive, as they revitalize cities, making them attractive to a diverse community. They do not account for people, particularly those with children, who want or need more urban housing that meets their needs as well as does a detached house. We need to find housing that allows various household types to live together at a density high enough to be economically feasible and a form that contributes positively to the neighborhood.

Throughout the latter part of the century, many architects have pointed toward existing housing typologies as a way to reverse mid-century mistakes. More recently, New Urbanists have proffered systems of rules for housing layered upon sets of public spaces and amenities that together form coherent, walkable neighborhoods. Generally, these approaches attempt to revive old patterns, with the hope that the nostalgic images counteract what has gone awry. What they do not do, however, is relate the image to the economics.

The Venerable Rowhouse

Two traditional types of dwellings seem to offer great possibilities, which is why they have proliferated. Whether a brownstone in the East or a Victorian in San Francisco, the venerable rowhouse achieves significant densities (as great as 50 units/acre), while providing most of the amenities of the detached single family house. The public and private domains are unambiguous, and the rows of attached dwellings reinforce the form of the city street. Streets are the public domain, linear rooms that serve both as corridors of movement and as a backdrop for social activity.

But in spite of these advantages and the efficient construction, the rowhouse lacks two elements. First, it does not easily accommodate the car. Each dwelling requires a curb cut that breaks the continuity—and ultimately the quality—of street and sidewalk.2 Furthermore, while the continuity of the building façades helps reinforce the urbanity of streets, the rowhouse does not provide for a semipublic realm, a place that provides a focus and a community amenity.

Courtyard Housing

I have always been a proponent of courtyard housing. The semi-public space formed by the housing around it serves as a territorial boundary, a protected respite from the city beyond. This, in fact, was the main motivation for the form. The first public housing in the country was a courtyard building meant to keep out the undesirable elements of early 20th century New York. But courtyard housing also has drawbacks. It, too, does not easily accommodate the automobile. Cars are parked on the outside, the city-side, of the buildings, destroying the relationship of the dwelling to the street. Repeating the form results in open lots with housing set beyond. There is no three-dimensional definition to the street, and little social life along it. The remedies, such as placing cars beneath the court, are costly. Parking beneath the unit also raises the house, reducing its immediate connection to the street, yard, and court.

The best feature of courtyard housing is also its disadvantage. The semi-public space focuses the activity inward, and in so doing diminishes the liveliness and friendliness of the street and ultimately its security.

While living in London during the mid-1960s, I became intrigued by that city’s eighteenth and nineteenth century housing squares (right). My initial interest was how the overall form provided a focus for the housing, but also an amenity for the neighborhood, in spite of the fact that the space was fenced and accessible by key only to those who lived around it (unless you’re Julia Roberts and Hugh Grant).

Years later I began to appreciate these places as a means of increasing density without excessive height. In their original incarnation, the dwellings around the square were large homes, sometimes with flats partly below grade and with apartments for the domestic staff above the garages or carriage houses in back. By the middle of the 1900s, many were divided by floors into flats. The units along the mews (narrow service access roads behind the main houses) became increasingly popular as independent dwellings, as did the basement or subway flats, which always had a separate entrance for services to the main house (below).

Most recently, as I searched in my own housing designs for ways to accommodate increasing numbers of automobiles, I looked again at the London squares as a form with ample parking for the numbers of units they now incorporated.

Throughout the thirty-five years, I have been intrigued by Georgian and Victorian housing squares of London and by all they seem to accomplish, and curious why we didn’t see more of it in this country. There are a few examples in the United States; South Park in San Francisco is but one, although it is not primarily housing and the park is more public. The courtyard housing of Los Angeles has many comparable features, but the open space is rarely even viewable by the public. I have assumed that we have not borrowed this form because many aspects of them would not meet our codes or zoning.

The upper level bedrooms, often in the attic space, are accessed by equally narrow, winding stairs. These rooms are usually on the fourth floor without a second means of exiting other than rooftop access requiring escape through another unit. This configuration would not be permissible under current US codes.

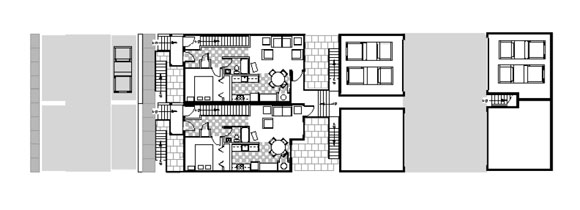

The typical width of these dwellings is 17 to 18 feet, accommodating a well-proportioned room, a hallway, and a stair. As bedrooms were inserted over time, this width now accommodates two rooms side-by-side, each very narrow. By our standards, bedrooms are at least 10 feet wide, so this dwelling width is insufficient.

Of the six housing squares I investigated, all in the Chelsea and Kensington areas of London, no two were alike, but there were several recurrent elements that are essential in establishing the common character.

Because the housing squares were primarily for the relatively wealthy and those who so aspired, each house has a prominent individual entry. The center units along each side of the square have an embellished cornice, making the entire group appear as one grand house.

In the more complex configurations, there are several dwelling prototypes. Occasionally, for example, there are dwellings immediately adjacent to the square, rather than the more common form in which the square stands independently, with a roadway on all sides. In a few cases, cars are parked in small parking courts formed by the unit itself. More often, parking is in the street between the house and square or in a garage reached through the mews in back.

Regardless of the relationship of the dwelling to the square and to the car, the units themselves are relatively consistent. There are the aforementioned lower units and their access courts immediately off the sidewalk. The main level is most often a few steps up, forming an entry porch with a portico. The main level originally contained public rooms (kitchen and dining), but the living and entertaining space were on the second floor, which is likely why the English refer to this floor as the first. This floor has a higher ceiling and a wonderful view to the square and often also to the yard in the rear.

The Proposal

While all my housing designs have courtyards of differing scales and uses, none emulates the London housing square, in spite of my long-standing interest in the form. Therefore, I set out, in the spirit of the “model tenements” movement of the late 1800s, to see if a design based on this form were possible using current US zoning, codes, and development standards.

My assumptions were that a design must attain at least thirty units/acre to make it economically feasible, plumbing must stack, and spans must be economical and recurrent. Furthermore, the design must incorporate a variety of unit types and sizes, so those with different incomes and household types can live together.

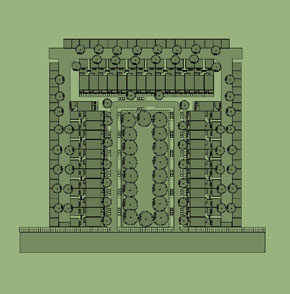

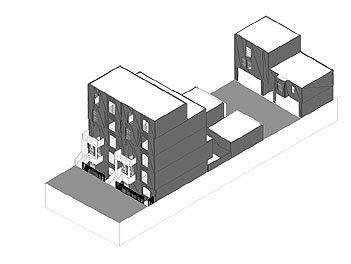

I discovered that it is indeed possible to achieve significant densities given our current standards for parking, unit types, and sizes. On a hypothetical four-acre rectangular site, 120 units fit comfortably, and, with a few liberal code interpretations, up to 160 units are possible. The essential elements of the London housing square are intact. A loop roadway around the square does not allow through traffic, but with minor adjustment, through traffic would be possible.

Placing an apartment partially below grade is necessary to gain the needed density within the overall height limitation of our codes for walk-up units and fire exiting. Within the same footprint and allowable height from grade, another unit is possible, albeit with excavation. Like the London examples, this unit would not be a full level down, and the unit above would be a few steps up, providing the front stoop and gracious entry. This slightly above grade entry would have to be interpreted as an “at grade” unit, or the upper levels would need an additional exit stair.

One important element of the traditional London housing square is the overall scale of the façades facing the square. Usually four or five stories, they give a gracious and grand feeling to the whole complex. Certainly, adding a top floor, even if it were an attic or “storage” space, provides for this same feeling, were the code to allow it. In this model, parking spaces and road widths are minimal but are within the current standards.

The garages tend to be smaller than optimal given our increasing numbers of large vehicles. (London seems to have very few SUVs, a function of the high price of gas and the difficulty of getting around in dense traffic.) The size of the garage is a result of keeping the module to twenty feet wide. At twenty feet, two cars can fit, even with a passage between garages to the mews, and two rooms can be side-by-side, although each is slightly less than the ten foot minimum we expect (below).

Housing around an open space is not a new concept. Because this form includes several typologies (rowhouse, courtyard housing, access mews, granny units), it makes possible economical, low-rise, walk-up housing at significant densities within our current space standards and zoning. At the same time it contributes a public amenity and maintains the urban fabric of streets. This housing can have many amenities and features that people, particularly those with families, have come to expect—individual entry, direct access to their car, views to a yard (albeit a shared yard), and a sense of community. Most importantly, many different types and sizes of units are possible, providing housing opportunities for the increasingly diverse populations in our cities.

- Davis, Sam, “Why Affordable Housing Isn’t,” in The Architecture of Affordable Housing, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), pp. 63-81.

- Jacobs, Allan B., Great Streets (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1993).

Author Sam Davis is Professor and former Chair of the Architecture Department at the University of California, Berkeley, and is principal of Davis & Joyce Architects. He was elevated to Fellowship in the AIA in 1985. He has edited The Form of Housing (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1977) and authored The Architecture of Affordable Housing (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995).

All images by the author.

Originally published 2nd quarter 2001, in arcCA 01.2, “Housing Complex.”