John Mutlow, FAIA, Principal of John V. Mutlow Architects and Professor of Architecture at the University of Southern California, has devoted much of his architectural career to the design of affordable housing with an emphasis on social considerations. That has included a little-discussed housing type – affordable housing for farmworkers – as well as other types of affordable housing.

In the following interview, David Thurman asks John about his unique experience with two farmworker housing projects, as well as other lessons from a career working on affordable housing.

DT: What were your original thoughts or motivations in pursuing affordable housing, and how did you begin doing this kind of work?

JM: It originated in two ways. One is, being English, I’m probably slightly more socially oriented and, because most of Europe is probably more socially oriented, concerned about your fellow man or fellow person. The second is that, when I was at UCLA grad school, I met up with Fred Case, who was the housing expert in the School of Management.

Through him, there was a contact with a community group in downtown Los Angeles, the Pico-Union Neighborhood Council, from a 93% absentee landlord-owned area immediately west of the Convention Center. The group came to UCLA for assistance, and my work was funded through a grant. There were five of us; I was the only technical consultant.

The Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA) had identified the area for redevelopment due to its deteriorating condition and absentee ownership; it predominantly consisted of aging, large, single-family houses inhabited by lower income renters, so the CRA wanted to do a redevelopment. Well, redevelopment means that you would actually demolish a large number of the units.

What I did as a technical advisor to the community was attend a series of community meetings, and I stood up on behalf of the community and opposed the schedule of CRA. I recommended that the tenants needed to be identified with what was going on in the area and what their needs were, because obviously if this were gentrified they would be moved out.

We eventually converted the redevelopment program to a neighborhood development program, saving many of the units, not necessarily demolishing the units. So, that’s how I initially got involved.

DT: After forming your own architectural practice, you became involved in two farmworker community projects, Cabrillo Village and Rancho Sespe. Some early farmworker housing consisted of little more than temporary camps with primitive, makeshift structures. Farmworkers still face continuing challenges, such as limited income, unstable employment, high rates of poverty, and housing overcrowding. How do you approach those kinds of challenges with the limited resources available?

JM: First, you have to find the resources. There are basically two, separate sources of funding, one for rehabilitation of existing structures, and one for constructing anew.

The history of these two projects offers a window into how farmworker housing evolved. Way back, there used to be farmworker camps licensed by the state. One of these sites, Camp Cabrillo in Saticoy, a small community in Ventura County, was a farm labor camp built in 1936 or thereabouts. Our project – called Cabrillo Village – eventually was built on the same site.

The original camp consisted of a series of single buildings that eventually grew to 100 units, plus three large halls where the seasonal laborers lived. They also had converted one of the buildings to a church. Over time, the original buildings for seasonal laborers were converted to family units, because many of the workers actually became long-term residents, especially in the citrus groves.

That gave the growers a reason for the evictions. Over a period of time, they knocked down about 10 units. Since there is no other housing in this area, the workers would have had to move to the towns, Filmore or Oxnard or Ventura, and there the rent would be much higher.

So, the farmworkers began to organize, and that’s when the first idea of housing as being theirs, not necessarily the growers’, took place. They were eventually able to obtain a small loan from the county to rehabilitate the existing dwelling units; later, they arranged for funding with the federal Farmers Home Administration (FHA), which was the beginning of developing our Cabrillo Village project, new housing with an additional 35 units.

DT: The Cabrillo Village and Rancho Sespe projects included working with funding agency guidelines and workers to design the units. It also led to integration of facilities to support these small communities. Can you talk a bit about your efforts in these areas?

JM: Cabrillo Village, I think, was successful because, when it started, they already had their own little supermarket that residents from the village ran. They also set up their own kiln and started producing their own ceramic tile. Then they started selling to a larger community. So, they had this sense of community belonging. Incidentally, this is something that also made the growers nervous, that temporary farmworkers workers were being identified as a “community.”

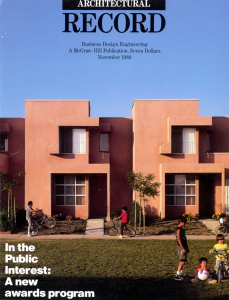

One of the requirements that came up was that residents wanted to have single-family houses. The second was that they wanted the lot size to be the same as the lot size of the existing small units. The problem was that the FHA, in this particular program, did not fund single-family housing. They only funded multi-family housing. So, we asked what that meant; the interpretation was that we had to have four attached units. That posed a challenge, because early in the discussions Cabrillo residents said, “We absolutely don’t want row housing.”

So, we looked at the guidelines and came up with what we called a “wrap” solution, where you had four units. Each unit was an L-shape, and together they formed a courtyard in the center. All four units were actually attached to each other, but there were only two front doors facing one street and two front doors facing the other street. When you approached them, they looked like single-family housing. So, we were able to meet the community needs and still meet the guidelines of FHA.

DT: The Rancho Sespe project began with similar issues that threatened to displace workers and that led to more permanent, worker-owned housing. How did that develop?

Rancho Sespe was similar to a farm labor camp, but the process of getting to a solution was very different. Rancho Sespe is one of the original long-time owners in this area, along Route 126, where there are all these citrus groves. They had the same problem when Cesar Chavez came around organizing. The growers wanted to demolish all of the temporary housing and even some of the permanent housing. The farmworkers got together and sued the owner, saying they couldn’t relocate them without alternative housing.

Because we had a lawsuit, and that takes time, the growers couldn’t immediately demolish the existing buildings. The workers needed approximately 100 units, so we planned for two phases of 50 units. The problem here was a lack of residentially zoned land anywhere in the area. It was all farmland. A second problem was: How do you buy land, when it’s all owned by the growers?

Eventually, the workers were able to find some compromised land that the growers had sold off much earlier, whose trees had reached the end of their life. They were able to buy this land, and at the same time were able to persuade the county to give them a zoning change. The Cabrillo Economic Development Corporation, which is a management corporation that helped Cabrillo, now also helped Rancho Sespe farmers.

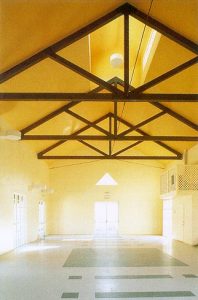

Initially, they received a loan for the first 50 units of housing, but on the understanding that the village we were designing was going to be 100 units. Once you have 100 units, you have a sufficient number of units that you can request auxiliary buildings. So, they requested a childcare center and an auxiliary building for their meetings, and they were able to have offices and a laundry room. An existing catch basin on the site became a soccer field.

We organized the site on a module based on the spacing of the orange trees. You may know, these orange groves are based on a 15 x 20 module. We planned the housing to fit within this grid, and our objective was that every unit we designed for the farmworkers would have a garden. They’re farmworkers, they like to grow things. And we saved a large number of the trees.

At the end our first presentation to the Rancho Sespe board, which was in a carport – that was their boardroom – there was absolute silence. I mean absolute. It’s the first time I’d ever been to a presentation where nobody said anything. We went away afterwards and had a drink commiserating, because we knew something wasn’t right.

It turned out, the one thing they didn’t like was that we had saved the orange trees. An orange tree to them represented work, so the last thing they wanted to do was go home, look into their rear garden, and see an orange tree. So, we went back three weeks later, kept all the trees, but replaced the orange trees with peach trees and all sorts of other fruit trees, and they loved it.

In both of the farmworker projects, we incorporated gardens into the project. At Cabrillo Village, we planted a front garden, but we also gave residents the opportunity of planting their own front gardens. At Rancho Sespe, there is a 70-foot swale, which is marked “no parking,” because it’s a flash flood zone; it spans nearly the entire length of the project and is now a community garden.

DT: The term “farmworker” implies seasonal or temporary work, following harvests; and they may or may not have all members of their family with them. How does farmworker housing account for such differences?

JM: One of the requirements of the Farmers Home Administration grant and loan was that the primary worker in the family had to be a farmworker. One of the problems that came with that was, if you’re a farmworker and you have an injury while you’re working, are you still a farmworker? Or if you’re a temporary worker, are you still a farmworker? Or if you become retired – because obviously everybody retires at a certain point – are you still a farmworker? Because both of these camps are cooperatives, owned by the farmworkers. On the first one, they bought the land from the grower. There were 80 units and they paid $1,000 a unit. Think about that.

At Cabrillo Village, a majority of the farmworkers were long-term residents. I don’t like to use the word “permanent,” but they were year-round workers; they also had three separate buildings that were primarily for the seasonal workers. In that sense, there is an important distinction between housing for long-term and more temporary, or seasonal workers, and it relates directly to funding restrictions.

The same was true at Rancho Sespe, although more of the workers there were seasonal. In terms of funding, the money that was coming from FHA wasn’t for seasonal workers; it was only for yearly workers. Other off-site housing is provided by the growers for some seasonal workers, so no FHA funding was used for these short-term workers.

DT: Looking overall at affordable housing projects, do you feel there are tried and true choices of configuration and materials for affordable housing?

JM: I would say yes. The most obvious is, if you are doing a very large project, make sure it doesn’t look like one project, even though it may be totally connected.

You can do that through clusters that can be connected by a bar building, which is what happened with some of my other affordable housing projects, such as the one at Darby, in Reseda, or in Spring Park, which is down south. That project, which is a 38-unit project for seniors, is L-shaped on a corner lot, at a higher density and taller than the adjacent buildings. They’re all two story. This is three. But what happened was that we differentiated the material of the two wings. So, one wing is primarily perforated metal and the other is stucco.

I say stucco and not in a negative sense. Stucco is a craft material in our region. I know it’s a material that people are very used to applying, but also it’s the least expensive material to clad your building with, by far. When you change from that material to something else, you have to do it in small amounts or very carefully. So, in many of our buildings, we use color, because color on stucco actually can give you a variation or change of mass. Because even when you change mass, you still have to have repetition, because repetition is what’s keeping the cost down.

On the L-shaped building, one wing has a perforated metal skin for sunshade. The other one has a Trex skin, as a screen for the balconies. Then the center link between the two wings is predominantly glass; it’s transparent. You can see right through the building from the front entrance through the lobby to the courtyard beyond. So, it looks like you have two buildings connected by a void rather than having one continuous building.

So, yes, I think you definitely do it through massing. We do not do a change of material simply within a cluster. The cluster itself may have a change of material from one cluster to another, because the identity of the cluster is important. In other words, if we had, for instance in Reseda, clusters of let’s see – one, two, three, four, five, six, twelve – we had three clusters of 12, but if you then break down the cluster of 12, you’d become quite confused as to what that cluster really represents. So, we tend not to break up linear buildings. We try to separate linear buildings into two separate pieces, so we don’t have a series of wall planes that keep changing from A to B, A-B-A-B. We’ll go from building A mass to building B mass. And that’s where we change materials. And we definitely change materials at the entrance.

DT: What does the future hold for both farmworker and affordable housing?

JM: I’ll come back to that question, but there’s something I wanted to mention. When you go through a funding agency, one of the critical things is to understand the language the agency uses in terms of architecture. Let me give you an example. We did a courtyard building in Pico-Union. It’s very typical of courtyards you have in West Hollywood. It’s a small family project, and the courtyard is important, because it gives you areas the children can play safely, especially young children. You don’t want them on the street anymore, which is where they used to be in Pico-Union; you want them in the courtyard.

In Southern California, it’s very hot in the summer, so you need to have some shade. Well, we put a gazebo in one of our projects, just a simple building with four corners and a pitched roof, nothing elaborate. We went in, and it came back and the landscape architect at HUD had put a cross through it and said, “No, sorry, we don’t allow gazebos.”

So, I went back to him and said, “Well, this is a problem. We’re in southern California. It’s very hot. We’ve got kids out there playing. At some point in time, they need to have a shaded area where they can sit down and chat, because they can’t always be out in the sun. So, can’t I have this structure?” And he said, “Yes.” I said, “Well, what should I call it?” He said, “Call it a shaded seating structure.” So, I went back in with exactly the same plan, exactly the same gazebo, changed the wording to “shaded seating structure,” put two seats in it, permanent seats, and it came back approved.

Now, back to your question about the future of affordable housing. Unfortunately, because of the cost of land, there’re only a limited number of strategies still available to make housing affordable.

One is, you end up building on land that has a problem, a problem the private developer doesn’t want to deal with. Either it’s the location or it’s the condition or it’s the neighborhood.

The second is, because of the high cost of land, affordable housing is moving out from where the workers need to work. So, affordable housing is increasingly going to be on the outskirts of towns rather than in the centers of towns.

The third, I think, is we will see smaller and smaller units and fewer amenities; ancillary buildings will disappear.

An opportunity is if the cities get involved. The city of Los Angeles, for instance, owns a great deal of property they’re not using, and right now the city is going through a program where they’re looking at many of their properties and seeing if they can convert them to affordable housing.

DT: Do you see an inspired new generation of affordable housing architects out there?

JM: I think there always are. There’s a whole group that came behind me, still out there, and I haven’t seen the next layer, but I fully anticipate that there’s another layer. You know, when I teach at USC, I see a lot of the younger faculty around, and half of them certainly are much more, shall we say, design-oriented, not socially oriented, but there’s always a few out there that are socially oriented. What I think is very interesting is that more of the housing now is done by non-profit developers, rather than for-profit developers, because the allowance money is very, very minimal.

These non-profit developers in many cases will work with architects. So, it’s quite often up to the architect to understand: you’ve got a budget and you have to do this many units, but the design – within that budget for that number of units – the architect has a certain amount of control over. It’s not like a dictatorial program at all.