arcCA asked a dozen and a half thought leaders to reflect on the most misunderstood notions, the most neglected problems, and the most underappreciated opportunities in sustainable design today. These are their responses.

The most misunderstood notion in sustainable design today is the idea that it’s a new thing. It’s not. Sustainability is very old school and grounded in common sense. Things were pretty much sustainable until our great, great, great grandparents starting making and selling each other so much stuff. Planned obsolescence sucks. eBay, craigslist and garage sales are cool. Air conditioning and fixed windows suck. Big windows with screens and fans are cool.

Our most neglected problem is the lack of consistent, intelligent conversation without hyperbole. I’d rather my kids’ ask me “Dad, what’s the meaning of life?” than “Dad, paper or plastic?” The tangled web we’ve woven with our global economies will freakin’ make your head explode… (When my kids ask me, “Dad, what’s the meaning of life?” I quickly answer, “Paper or plastic!” Then I leave the room. My wife tells me this might be child abuse.)

Not everything needs to be shiny and new. Not having to constantly upgrade (bigger, faster, stronger) would help. And old-fashioned concepts like “sharing, trading, and bartering” are underrated and underused.

I often think about my drive out to California from New Orleans twenty-plus years ago. Me, my girlfriend, and all our stuff in a Volkswagen Rabbit convertible. All our stuff. I doubt I’ll ever get back to that light a footprint, but I am trying to downsize and work with what I’ve got. I’m not living the monastic, anti-materialistic life (ask my wife about my guitar collection). But I am asking myself more often, “Do I really need this, or do I just want it?” And I’m allowing myself time to think before answering, “Hell yes, I need it.” “Keep it simple, stupid” is my new mantra.

Life Cycle Design / Biophilic Design / Carbon Balance

The life cycle can be designed and planned—and it does not require some linear check list (LEED, SmartCode, BREEAM, . . . ), nor some abstraction that you only hope to understand (Integrative Design, Living Building Challenge), nor even some rigorous LCA ( life cycle analysis) that becomes difficult as a design tool. The key to life cycle is that it is a cycle, in fact a cycle within cycles, and can become a web of life regenerating the original resources —as in re-sourcing—and to a certain degree at any scale building to city to country. We can no longer do one half without the other—“solar” driven water harvesting without solar driven treatment, solar created, rapidly renewable building materials without flexible, reusable, open buildings using localized mega flora, which is waste water regenerated. Food production can no longer occur without bio-intensified rebuilding of the growing medium. If you have the unfortunate education that says, “I cannot do this without a checklist,” then make sure that all the ingredients within the list have the potential to be a cycle. Sustainability no longer fits into the conservation paradigm; it is a process of sustaining for further information at the building scale, community scale, or national scale. (Please contact us concerning EcoBalance Planning and Design, or our national material flow model with 12.5 million businesses and all their green house gases, criteria air pollutants, and toxic release.)

Biophilia need not be limited to looking out the window to a forested meadow or a picture on the wall or the rhythms of light affecting your psychological well-being. Biophila needs to once again become part of the brain, but this time—since we have evolved over the last 10,000 years past the primitive brain—we now have to work on the advanced neocortex part of the brain. Which means respect for a whole new set of rhythms. According to neuroscience, the neocortex is also responsible for interval pattern recognition—the understanding of the durations between repeating events—responding to activity sequences and controlling our ability to adapt when confronted with new ones. New information, new patterns, crowd sourcing: the stuff that the neocortex loves. This is in contrast to the part of the brain associated with the circadian clock, the daily and seasonal rhythms overly focused on in biophilic design.

The spaces we design need to be creating a forest of opportunities (air, water, food, energy, materials cycles) that re-sink us into the life events that enable survival—simulating, extrapolating, comparing—all part of a new level of design science that is more critical than ever. Encapsulating macro-level natural processes on a micro scale will increase our ability to synchronize the brain with nature. Everyday processes designed as events so that occupants witness more thoroughly their interaction with the life cycle that creates them. Perhaps the reason we are quickening and reducing in scale all our life support cycles in the buildings that we call sustainable is the fact that the brain needs it.

Carbon balanced design: this over-concentrated effort misses the vote in two ways:

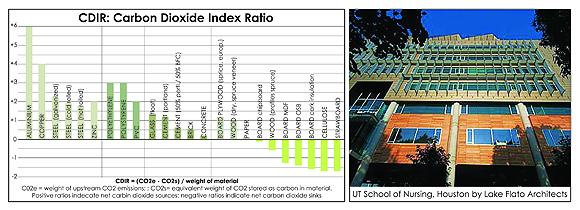

a) Before we think in terms of operational, mechanical balancing, we can balance the embodied carbon in our building by balancing the net life cycle problem materials (i.e., the metals) with the net life cycle sequesterers (i.e., woody materials) and appropriately mixing the two ( see the Carbon Dioxide Intensity ratio on our web site). It produces a beautiful regional design motif: metals need wood, and wood comes from place.

b) Carbon balancing (or neutrality) really needs to be referred to as climate neutrality; after all, methane, carbon monoxide, and nitrous oxide are all as or more serious problems than carbon, and the fact is that some of these are easier to deal with and more understandable. Carbon is the by-product of nearly every industrial process known. Methane is more a point source, from discarded woody-based building materials (instead, we can develop building systems for reuse) and sewage treatment (we can use the methane as fuel); even the cow can be controlled, as demonstrated in the Netherlands, via its feed. Pretty important stuff, since we can make major inroads in five years instead of one hundred years, by which time it could be irreversible. Please, Ed Mazria, the big picture is even bigger.

“On what planet do you spend most of your time?”

Agriculture and civilization have developed during the relatively stable and benign phase of climate conditions that have persisted over the past 10,000 years. Humanity is currently engaged in a planetary-scale experiment in which this climate is being modified on time scales perceptible within a single human lifetime. The climate you grew up with is not the climate you’ll enjoy during your end days, much less that which your grandchildren will experience.

My house was built in 1913 to shield its inhabitants from external forces of rain, snow, wind, and temperature, according to assumptions of interior comfort, lighting, and ventilation, and costs of heating and cooling, all of which are substantially out of step with the external environment and the inhabitants’ expectations of 2009.

Perhaps the most neglected problem or issue in sustainable design and construction today is that the environmental parameters to which designers respond are changing, and quickly enough so that the operational envelope of the built environment is certain to change during the lifetime of the structures that inhabit it. In what ways must designers contribute to adaptation and mitigation of climate change? On what planet will their buildings spend most of their time?

Forget that this task of planet saving is not possible in the time required. Don’t be put off by people who know what is not possible. Do what needs to be done, and check to see if it was impossible only after you are done.

When asked if I am pessimistic or optimistic about the future, my answer is always the same: If you look at the science about what is happening on earth and aren’t pessimistic, you don’t understand the data. But if you meet the people who are working to restore this earth and the lives of the poor, and you aren’t optimistic, you haven’t got a pulse.

The living world is not “out there” somewhere, but in your heart. What do we know about life? In the words of biologist Janine Benyus, life creates the conditions that are conducive to life. I can think of no better motto for a future economy.

We have tens of thousands of abandoned homes without people and tens of thousands of abandoned people without homes. We have failed bankers advising failed regulators on how to save failed assets. We are the only species on the planet without full employment. Brilliant. We have an economy that tells us that it is cheaper to destroy earth in real time rather than renew, restore, and sustain it. You can print money to bail out a bank but you can’t print life to bail out a planet.

At present we are stealing the future, selling it in the present, and calling it gross domestic product. We can just as easily have an economy that is based on healing the future instead of stealing it. We can either create assets for the future or take the assets of the future. One is called restoration and the other exploitation. And whenever we exploit the earth we exploit people and cause untold suffering. Working for the earth is not a way to get rich, it is a way to be rich.

We all know that sustainable design has been a major trend in recent years and continues to grow. The next phase of that trend goes beyond “sustainable” to “actively beneficial,” and this is a worldwide trend. Due to the pressures of energy use and economic necessity, it will no longer be possible to simply create a sustainable building—facilities of all kinds will be expected to generate some or all of their own power, use less energy, purify their own wastewater, offer wildlife habitats, and restore local ecosystems. People will also expect these places to provide healthy, functional, and attractive places to work, shop, gather, and be pleasing to look at and experience.

Successful prototype projects have already been constructed, most famously the Adam Joseph Lewis Center at Oberlin College.

As competition heats up for talented individuals, the proverbial “war for talent” will go on worldwide for those with “green” abilities, experience, and solid credentials. Already, the pressure is on for firms to do more than simply be LEED certified; clients are seeking firms experienced in innovative solutions. Both our greater national interest and our local communities will demand that every project do much more to benefit the community than simply be a functional piece of infrastructure.

It’s hard to find a person who is against sustainability. I can think of only two people I know. Sustainability is in the same league as motherhood and apple pie. But in most conversations, sustainability’s approval rating nosedives somewhere between 14 and 31 seconds in. That’s usually the time when the gauzy notion of sustainability inevitably gives way to defining what it is (30 point drop) or doing something about it (free fall).

What’s going on here? For one, humans are good at using our big brains to know a lot. But it doesn’t always translate into doing a lot. Second, we are on sustainability overwhelm. Staying current is like drinking from a fire hose—everyday. And that’s hard to swallow. Third, amid this explosive growth in knowledge and information, the very meaning of sustainability has been diluted to the point of meaning just about anything, and thus meaning nothing.

We all support motherhood, apple pie, and sustainability. We know what the first two mean, and we know how to create them. Not so sustainability. Even the Brundtland Commission’s definition—development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs—is difficult to apply to the here-and-now of one’s own life. Paper or plastic?

Without an explicit, shared agreement about the meaning of sustainability, even the well-informed and well meaning among us cannot make much progress. Indeed, this lack of clarity enables avoiding the most neglected problem in sustainable design today: time. There are many projections about when catastrophic environmental events will take place. It’s hard to know how accurate they are, and it doesn’t matter. The plain fact is that we don’t have time to wait and find out if the projections are correct. What matters is taking smart, bold steps now, because here’s what we do know: the longer it takes to start meaningful healing of the earth, the less likely we are to have a viable future. In short, we don’t have time to waste.

Is there any hope? Yes, and it’s not false hope. Design—and design thinking—as a set of solution-seeking tools, is spreading to every corner of the world. Indeed, we are all designers now, and optimism is an onboard skill of designers (sustainable or otherwise). More importantly, healing the earth is igniting the largest movement of human energy in the history of the planet. It is a movement without precedent, amorphous, unorganized, instinctive, and blessedly uncontrollable. Literally billions of people are on the job. It is already the single largest public works project ever.

If we can get as good at making sustainability as we are at making motherhood and making apple pie, we could be very happy, be well-fed, and live long, balanced lives. Cloth or disposable?

While LEED has been phenomenal in elevating the awareness and standard for resource efficiency in buildings, it has done a disservice to the industry by confusing the real goal of sustainability. Of course we have to get the building envelope and systems right, but that is the low hanging fruit. Where we build, what we build, why we build and, in many cases, even if we build are as important as how we build. And a whole lot more complex.

A “green” Wal-Mart in a suburb of Chicago that takes a half hour to drive to in order to fill up oversized cars with stuff people don’t really need (much of it made of plastics and shipped here from China) is not sustainable. A “green,” 10,000 square foot, third home in Hawaii used a month a year is not sustainable, even if the owners share a private jet with their wealthy neighbors.

The sustainability challenge is not about building what we’ve always built more efficiently. It will take a whole new mindset and map. And climate change accelerates our need to think in the big picture and puts issues of land use right up there with fuel efficiency and clean energy technologies. Once again, California has taken a leadership role with AB32, legislating an 80% reduction of GHG emissions by 2050. Cities and counties are following with individual Climate Action Plans. Designers now need to take up the challenge.

Back in the early ‘80s, when Title 24 was first adopted in California, it raised the building efficiency standards in the state well above the national average and has since saved Californians $56 billion in energy costs. We need to legislate LEED so that it becomes the new standard rather than a competition for differentiation. As Thomas Friedman says, we’ll be green when we don’t need to call it green. Then we can move to the more complex challenges of sustainability that require a deeper understanding of trade-offs, rethinking a lot of assumptions and developing new metrics and models. Most of all, we need a whole systems approach that includes buildings within the larger framework of land use, transportation, food, energy, and climate.

The opportunity for design professionals today is to become fully informed about the full implications of building (what, where, why, if, and how) in order to truly LEAD (and inspire!) us to a sustainable future.

The concern for sustainability isn’t new to the design professions at all. Being able to do something about it at a national and global scale as a movement that is latitudinally broad across professions and longitudinally deep into a profession—that’s what is really new.

Websites that let you share information are a tremendous opportunity, but they sometimes have too much information to be truly useful, and there are so many sources of info that it’s unclear where to go. We need a WIKIpedia for the sustainability movement, or an Amazon.com substore (call it Greenazon.com) where you can only buy items that support sustainability and aren’t home delivered but instead force you to buy locally.

The most misunderstood notion, today, is the definition of a green building. Although many have used LEED as the definer, it has been an unfair burden on LEED and has led to unfair expectations. LEED is a system that rates buildings against a consistent set of metrics. It is designed to be a market friendly tool and has been enormously successful in shifting the paradigm in design and construction to integrate nature and technology more honestly. As such, it is the first step toward the green building aspiration—the regenerative building, a term coined by John Lyle. The next step is to consider the definition of sustainability as defined by the U.N. World Commission on Environment and Development: “To meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” And then we can look at the Hanover Principles and the Living Building Challenge as paths towards the aspiration. Ultimately, a green building aspiration cannot be determined by minimums but by proactive dreams that go beyond what we can imagine.

I would like to see us return to the passive building as an aspiration. So much emphasis has been placed on energy- and water-using systems and very little on the actual performance of the architecture. All of our favorite buildings through history are passive buildings. It’s time for us to remember the principles of our architectural heritage and build on them for innovation.

Our quality of life is directly connected to our experience of the natural world. Access to the outdoors—by means of a courtyard, daylighting, natural ventilation, a garden—increases our health and wellbeing. Sustainability is often defined using the triple bottom line: people, planet, and profit. However, where carbon reduction and energy savings have been the environmental and economic highlights, the quality of life for building occupants has been overlooked and has great opportunities for innovation. There are many building types in many climate zones that can function with 100% daylight autonomy, natural views, and natural ventilation. The connection to the outdoors is not just an energy issue; it is a quality of life imperative.

The only way we can reach our goals in carbon neutrality, energy independence, and water conservation is through community. Community can take many forms: a municipality, a neighborhood, a cross-disciplinary project team… The integration of diverse knowledge and experience is a powerful tool for understanding and solving design issues with sustainable intentions. At the same time, many models of sustainable development are available: eco-industrial parks such as Kalundborg, Denmark; multi-use developments such as Dockside Green; and eco-villages around the world.

Nowhere have we slumbered more than in the area of water. I expect our descendants will be incredulous: “Do you know that they used to wash their cars with this stuff?!!” they will say as they sip rare “2016 Glacier National Park” cuvee. In the U.S. today, we drink only 3% of the potable water piped to our homes; the rest is put to work as a solvent, lubricant, transporter, heat conductor, and coolant, among other things. Elsewhere, 25 million people a year are displaced as refugees, not because of war, but because their water is no longer drinkable.

The good news is that we can reap great benefits from wise water use almost immediately, using common sense and simple procedures. Water is the ultimate recyclable substance, after all, and if we avoid its chemical pollution, those molecules that once rode on the backs of wooly mammoths as snow can still be used for your next pitcher of lemonade. Its wise use is also a multiplier. For example, General Electric found that using less water in its manufacturing meant using less energy to run pumps and motors and less air pollution. Finally, its almost magical property of bringing forth life is one of the greatest gifts of our natural world. It will be key to the next, regenerative phase of the green design movement. Water use is the “low-hanging fruit” of sustainable design, but, if ignored, will be the next big crisis in the developed world.

There are a lot of myths surrounding sustainable design, but probably the most pervasive has to do with cost. People want to know the “green premium” or “payback” of every single green feature, technology, or system. But they are asking the wrong question. First off, there are many shades of green. Many things cost no more than conventional construction, some things cost less, some things cost more. But even that answer isn’t nuanced enough. Buildings are systems, and trying to price an isolated component of a system is always the wrong approach. A properly designed green building might be full of technologies that have higher first costs but result in savings in other parts of the system, for a minimal net additional cost or even a reduction. There are examples of LEED Gold or Platinum projects with zero cost premiums. It all has to do with what you value, as well. People always want to know what the payback is on a solar array—but they never ask what the payback is on their stainless steel appliances or the two-car garage on their house. When it comes to cost, green design often gets asked unfair questions that are not asked relative to other values in a building.

I consider most promising the program Cascadia has launched to certify Living Buildings—to offer a vision of transformative change in the built environment following simple, pragmatic rules for design. When people read it, they think it’s too stringent—yet many are proving that it’s possible today. With over sixty projects in various stages of design and construction around North America, the Living Building Challenge offers hope for a truly sustainable built environment. We encourage every architect, engineer, and developer to begin to use the challenge as a design tool, as a guide, as a set of aspirational tools—and ultimately as the new benchmark for true sustainability. Check it out at ILBI.org.

Truly sustainable efforts depend on strategies that balance environmental and social sustainability. Environmental efforts independent of, or at odds with, basic human needs such as health, justice, and pleasure will be short-lived at best. The technical aspect of sustainability—how to lower consumption and toxic impacts—is the easy part. It will quickly become relatively dull and mundane, like the effort it takes to keep buildings from falling down. The mind-numbingly difficult and interesting part is how we can make the cultural shift to a sustainable existence. What can substitute for the joy of more? More things, more space, more innovation seem an integral part of who we are as a species. Can we keep ourselves from devouring our way into oblivion? Our greatest opportunity lies in doing less. Discovering innovation by rethinking what we have. Can we repurpose instead of rebuild, rediscover instead of reinvent?

I’m a communications designer as well as a design educator. I’m not an architect, although I frequently partner with them. I’m interested in the things I design being part of big pictures, not isolated artifacts. The work I’m doing with my students and the projects in my studio have the goal of helping audiences imagine compelling alternatives to the unsustainable norms of the American lifestyle.

An example of the process of providing new imagery also exemplifies a new way of seeing the designer’s role. My students produced Rethink Your Green as part of the Index: | AIGA Aspen Design Challenge: Designing Water’s Future, an international competition to address the water crisis. Understanding that in Los Angeles the largest contributor to this problem was the watering of LA’s lawns, they realized their design “problem” was to change behavior. That meant first changing the ideal of a lush, green lawn deeply imbedded in the American psyche—in part driven by Hollywood—as part of what constitutes “house” and “home.” They needed to design a system of communication, one that could reach different audiences with differing values about lawns and lifestyles; address different stakeholders, such as gardeners, who need to know how to maintain alternative landscapes, and retailers who would provide access to the products that contribute to change. In other words, communication or graphic designers have to move beyond thinking of what we do as designing isolated artifacts. The answer is no longer a poster; it’s a communications system that recognizes that problems are not isolated from their contexts.

Buildings that have lasted over time, such as the Ferry Building in SF or Union Station in LA, are those that have created real value to the community—as gathering places, as community icons, or simply to serve a function. These types of buildings are truly sustainable. Sustainable building is not about specifying products with green attributes, or exceeding T-24, or even being LEED certified. It is about creating places that, when their typical life span has ended, we don’t demolish and rebuild new, but instead find ways to reuse, whether as originally intended or by adapting them to suit current needs. What this means, then, is that when building a new building, we think of how it will contribute to the fabric of the community in thirty years, in fifty years, and even in a hundred years. Our discussions about sustainable design need to begin not with what LEED rating we are going to achieve, but with how we build a building that creates value for future generations.

“Let us first worry about whether man is becoming more stupid, more credulous, more weakminded, whether there is a crisis in comprehension or imagination.”—Paul Valery

We face a crisis of imagination in the design of sustainable architecture. Day by day, I work on the incremental act of improving the ecological impact of buildings by designing, consulting, and teaching. In practice as well as in academia we all too often focus on accounting, practicing sustainability as an additive process that begins with the status quo and improves it move by move, spec by spec, credit by credit. Our accounting systems, whether Title 24, CHPS or LEED, have had a large impact on the industry of making buildings, and it has been a good one relative to the environment-be-damned attitude of the postmodern and deconstructivist years.

But the popularization of sustainable design has led to guidelines and baselines—achieving the minimal without really engaging the transformative possibilities of living lightly on the land, repairing the earth instead of merely degrading it less, discovering new ways of dwelling between earth and sky.

Guidelines are my personal bête noire. When we already know that the building must face north and south, we have lost the possibility of rising with the sun and toasting the sunset from our homes. When a low-energy house for Germany takes root in coastal California and still minimizes skin and breathes with a heat exchanger, our imagination is hibernating if not lost altogether.We have developed our competence, but possibly at the cost of our imagination.

Then there are days the question of comprehension haunts me. On those brilliant California mornings that breed optimism, I can almost believe we will save our home on this planet without civil strife and political crisis. Perhaps most especially on those optimistic days, however, I realize that we suffer from a crisis of comprehension of the challenge facing us. It is in our nature. No matter the work and exhortations of Al Gore or Ed Mazria, the dark pessimism of James Lovelock or the latest photos from the poles. Day by day we continue to accept compromise and incremental improvements as “progress,” but towards what end?

Perhaps comprehension and imagination are not so fully separate. We need both in spades, everyday.

The most neglected issue in sustainable design today is that our institutions—including the design professions, lawmakers, and regulators—are not designed to collaborate toward solving the large, systemic problems that threaten human survival. Professor Harold Gilbert, a Harvard psychologist, writes, “We’re far more sensitive to changes that are instantaneous than those that are gradual. We yawn at a slow melting of the glaciers, while if they shrank overnight we might take to the streets. In short, we’re brilliantly programmed to act on the risks that confronted us in the Pleistocene Age. We’re less adept with 21st-century challenges.”

Our country has led technological progress for a long time, yet in terms of facing the challenges of peak oil and climate change, we are far behind Western Europe. Perhaps it is American exceptionalism and the human tendency to believe that we will somehow escape the unpleasant realities that will affect all species and all humankind. The use of the term “sustainability” indeed gives us a false sense of security, in that it implies that it is possible through technological change to design our way out of larger processes of ecological collapse and climate chaos. I prefer the terms “adaptive design” and “resilient design,” which suggest that the real work is our design response to certain uncertainty.

Modern materialistic culture has thrived through the development of our left-brain capacity to reduce all problems to finite, rational, solution algorithms. Yet, the design problems we face consist of multi-dimensional, complex systems issues that cross traditional disciplines and knowledge sets. We have to develop whole new mind sets, ways of working together, communicating across mind sets and tossing away old habits, inventing new collaborative processes to overcome today’s fragmented, bunker mentality. We need to shift our focus from left brain to right brain, which is the basis for all design. Remember the old dictum, “Think outside the box”? Our problem is that thinking is the box. We need to start experiencing our small world with our whole being.

The Three R’s of design for the 21st Century are: restoration, regeneration, resiliency. This means integrating building design within a larger context of community design and the integral ecological design of food, water, energy, and recycling systems at every scale. Most of today’s middle school students know the mantra, “Materials cycle, energy flows, life webs.” Today’s designers need to imprint that in their being.

The public as well as practitioners believe if a building attaints a LEED rating, it is “sustainable.” Although LEED is getting more sophisticated, there is typically a significant gap between a rating and building performance. To fill this gap, we need to understand how our existing buildings are performing through the use of post-occupancy surveys, while simultaneously moving toward the development and implementation of ubiquitous building sensors that monitor performance on a continual basis and make adjustments or alert users to correct problems. At the College of Environmental Design, Berkeley, building science faculty at our Center for Environmental Design Research (CEDR) are working with scientists from across the university to develop automated building monitoring systems that are linked to sophisticated simulation software, ultimately enabling us to test the energy implications of alternative design specifications.

The most neglected issue today is urban metabolism. Buildings are part of a much larger system of inputs and outputs, and how they fit into this system is vital. Inputs include energy, water, raw materials, people, animals, plants; outputs are wastewater, various forms of pollution, and solid waste. Buildings should be designed on the basis of biomimicry, and once they receive an initial allocation of inputs, they should recycle and reuse those inputs on an ongoing basis. This implies building systems and urban neighborhoods that produce energy and food, recycle all water, capture and reuse waste outputs, etc. While not self-sufficient, such ultra-high performance buildings are the next move toward sustainability—the “post-green” era.

The aesthetic opportunity is that we have not figured out the answer to the question, “What does sustainability look like?” Building a “green” building used to imply trade-offs between beauty and eco-efficiency. Those days are past, but we still have a large gap between the design vocabularies of highly acclaimed object-buildings and ultra-sustainable projects. Do we need to jettison some of the older vocabulary? Invent new and widely embraced vocabularies? There are vast opportunities for inventive and persuasive designers to lead us toward a better understanding of the aesthetic possibilities of sustainable design.

The practical opportunity is the retrofit and renovation of existing buildings. Although high performance is vital for new construction, we need an army of designers and construction workers to make existing houses, commercial buildings, and industrial facilities radically more energy and water efficient. This is a key strategy for building a greener and more inclusive economy. As professional designers, we know that, in order to fast-forward sustainable urbanism, we will have to mobilize politically to attack this issue at a scale that matters.

Originally published 3rd quarter 2009, in arcCA 09.3, “Beyond LEED.”