Hired as a designer and draftsman by Joseph Esherick in 1962 and now CEO and Senior Design Principal of Esherick, Homsey, Dodge & Davis, Chuck Davis, FAIA, has been a key contributor to the firm’s body of work and an important developer of its architectural philosophy. By taking the philosophical foundations established by Esherick and applying them to the design of major academic, institutional, and private projects, Davis has expanded the scope and scale of the firm’s work.

During the first years of his career, “I learned all I could about all the aspects of being an architect from Joe Esherick, George Homsey, and Peter Dodge. It was what one could call being an intern and resident physician all rolled into one. The senior physician was Joe, the lead physician on the floor was George, and Peter was the quiet, intellectual counterpart to George and the one who was often the voice of reason. None of our roles were easy, as Joe thought long and hard about what we were all doing and often redirected our efforts to get the very best out of all of us.”

Davis’ approach is quintessentially Californian—inclusive rather than exclusive, inventive and spontaneous rather than formal or pedantic. Based on free association and the invention of the moment, Davis’s style explodes preconceived notions of form and style, leading to a type of jazz architecture, one born new in each instance. What results are structures extremely diverse in their form and articulation, yet exceedingly well suited to their sites, their programs, and the needs of the users.

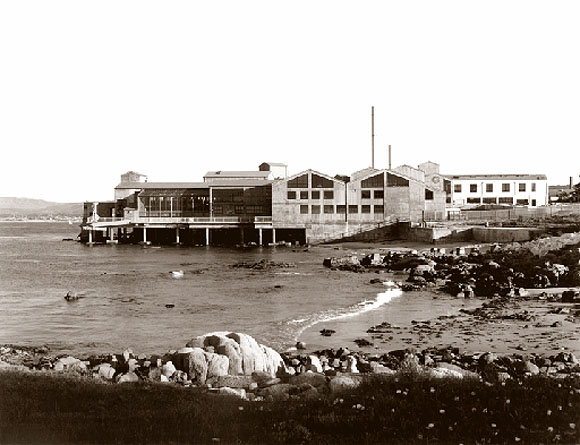

The opportunity of a lifetime came with the Monterey Bay Aquarium, Davis’s first aquarium project, won with his promise to set up an office on the site and to share space with the marine biologists who would be developing the program. “For the next five and one-half months,” Davis recalls, “I roamed back and forth between the biologists in the lab and my people in the next room, trying to understand the myriad technical requirements of taking care of fish and mammals, as well as trying to fashion a building that would fit the context of Cannery Row. While derelict to the casual eye, the cannery was alive and wonderful where it was—literally a breath-taking series of interior spaces, all different and random, built to the needs of the various manufacturing processes, and the building responded in kind.” Davis served as designer, project manager, architect, and politician with the city, the Coastal Commission, and the owners of Cannery Row.

A direct result of this integrative, complex, and thoroughgoing process is a transformation in current aquarium design. A new methodology—based upon a harmonious union of marine science, materials research, visitor experience, aquarium exhibitry, and a deep understanding of aquatic habitats, emerged from Chuck Davis’s experience at Monterey Bay.

Understanding the technology and methods of construction is crucial to Davis for the creation of a good building. The son of an army engineer, Davis advanced his Berkeley architecture education in Europe, supervising construction projects for the Army Corps of Engineers. Building bridges, warehouses, and runways for the Corps gave Davis a firsthand education in heavy construction and a respect for the work of those who build. His nuts-and-bolts approach to projects has benefited the firm, giving it a well-earned reputation for technical competence, particularly in challenging programmatic projects such as laboratories and aquariums, as well as libraries, which carry important symbolic weight as well.

The Science Library for UC Santa Cruz sits within a spectacular grove of redwoods, zigzagging through the grove and preserving as many of the trees as possible.

Glassy, multi-story spaces around the perimeter of the building echo the verticality of the trees and create a feeling in users of sitting in the forest while studying.

The Doe Library at UC Berkeley takes an entirely different approach, demonstrating Davis’s dictum that, when beginning the design process, one should “check one’s ego at the door.” The building is a major addition to the historic main campus library adjacent to the Berkeley Memorial Glade—an important open space in the center of the campus. A new building might have destroyed the glade and hidden the main façade of the existing building; instead, the addition is buried beneath the glade, with huge skylights that bring light deep into the building. Its roof forms a new entry plaza to the historic building.

Davis has long been interested in the fabric of cities, and has been an active participant in the AIA’s R/UDAT process (Regional/Urban Design Assistance Teams). He has been chairman of R/UDAT teams—an important leadership position—for eight cities since 1981, including Salt Lake City, Santa Fe, Austin, and Boise.

Davis regularly serves on design award juries, has published numerous papers and delivered lectures on a variety of subjects, and has taught frequently at UC Berkeley and other universities. He is a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects and served as the vice-president of the San Francisco Chapter from 1990 to 1992. He has an ongoing interest in mechanical things and has designed a collection of sturdy, yet comfortable, chairs meant for academic use.

This article was prepared by the staff of EHDD (Esherick, Homsey, Dodge & Davis).

Originally published 3rd quarter 2003, in arcCA 03.3, “Done Good.”