Paffard Keatinge-Clay’s ambitious but numerically modest architectural output is located primarily in the Bay Area, an ostensibly liberal, intellectual microclimate that has never been able to bring itself to embrace Modern architecture with the gusto of our neighbors in the southern portion of the state. The buildings were constructed mostly between the early 1960s and mid-1970s. Unsurprisingly, they have sufffered a broad, if predictable, spectrum of neglect. What is surprising is how many of these works have persevered relatively intact over the approximately forty years since their making.

Having spent the last several years researching his work and visiting the buildings that still exist, I can offer a brief study of a cross section of preservation strategies, almost all accidental, across a realm which is both geographically and temporally finite. What is it about these works that merits preservation, and what has allowed them to survive (or not) to the present?

PKC

Practicing architecture in San Francisco from 1960 until 1975, Paffard Keatinge-Clay left behind a legacy of architectural work in the Bay Area—some realized, others for which only paper documentation exists. The buildings are indices of a career marked in equal measure by synthesis and ambition and characterized by a series of apprenticeships with major architectural figures active between late 1940 and early 1960: Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. Keatinge-Clay also shared an association with a host of other notable designers, including Myron Goldsmith, Mies van der Rohe, Sigfried Gidieon, Richard Neutra, Charles and Ray Eames, Erno Goldfinger, and Rafael Soriano.

Born near Stonehenge in England, Keatinge-Clay grew up in the town of Teffont. He received his education from the Architectural Association in London, dual majoring in Architecture and Structural Engineering. His professional career began in Goldfinger’s London office, while he was still a student.

Keatinge-Clay worked for approximately one year in the studio of famed French architect Le Corbusier at 7 Rue de Sevres in Paris in 1948. While there, his work focused primarily on the Unite d’Habitation in Marseilles and on the plan for the town of Saint Die. After graduating, Keatinge-Clay left Europe, traveled across America, and apprenticed for a year at Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin studios in both Wisconsin and Arizona.

In the early 1950s, Keatinge-Clay moved to Chicago, where he worked at the Chicago offices of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill on the Inland Steel and Harris Bank and Trust Buildings with Bruce Graham and Walter Netsch. He later transferred to the San Francisco office of SOM, where he executed the Great Western Savings and Loan Building in Gardena, California. It was from here, in 1961, that he left the firm and began his own office.

During the fourteen-year period from 1961 to 1975, Keatinge-Clay produced several buildings, many of which remain today. The most well-known and documented of these projects is a large-scale addition to the San Francisco Art Institute. Finally, in what would turn out to be both the most ambitious and professionally tumultuous project of his career, he was selected to design the Student Union building at San Francisco State University. Difficulties, both technical and legal, resulted in his eventual departure from the U.S. to Canada, followed by an exodus through North Africa sometime in the late 1970s and early 1980s. He lives today in Malaga, Spain, and practices as a sculptor.

Works/Strategies

The following buildings still exist today, and most can be visited at will. What follows are some thoughts about the nature of what changes have taken place and what they mean to the intellectual intent of the built work.

Great Western Savings and Loan – Sympathetic Program/Apathetic Stewardship

The Great Western Savings and Loan was intended as a prototype branch bank, which would be rolled out across the state (and later the country) as this local bank expanded throughout the ‘60s and ‘70s. The prototype was, however, prohibitively expensive, by virtue of its ambitious structural tectonics, which necessitated a continuous, seventy-two-hour pour of concrete to produce the signature roof. The building’s carefully executed, exposed architectural concrete has been painted throughout the exterior. The interior concrete of the roof remains exposed as intended, but the floor plan has been radically revised to include the ballistic resistant glazing assemblies characteristic of most branch banks in underserved, urban environments.

With minor exceptions, including the infilling of the drive-through teller windows and the addition of a supplemental vault, the building parti and massing remain legible. The painting of the exterior surfaces is a theme that will be regrettably repeated.

Northridge Medical Arts Building – Erasure of Identity = Palimpsest of Presence

The Northridge Medical Arts Building was (technically, still is) a small medical office building adjacent to the Northridge campus of California State University and coincidentally located a few feet from the epicenter of the 1994 Northridge earthquake. Julius Shulman documented the building photographically in 1964.

At an unknown point in the last five to ten years, perhaps following the earthquake, the building was completely stripped of its characteristic façades, the floor plates were extended out into the area of the brise soleil, and the whole building was reclad.

The building is virtually unidentifiable today, Keatinge-Clay’s authorship verifiable only by the Corbusian handrails in the egress stairs and the steeply angled elevator machine room on the roof. Presumably, demolition of the signature elements of the building’s architecture were too difficult and/or structurally impossible; thus one might imagine the possibility of the canopy and a cast in-place egress graphic lurking somewhere within a peach stucco-clad confection.

Tamalpais Pavilion – Obfuscation by Accretion

This small, beton brut, Miesian structure was the architect’s own house and a showcase for post-tensioned concrete engineering. A series of subsequent owners has inflicted almost every indignity to the structure that can be imagined without demolishing it, and yet the clarity of the original idea can still be heard, if only in a whisper. The potential exists for the building to be returned to a state more in keeping with the ideas underpinning its conception, but the contemporary economics of real estate in Mill Valley argue strongly against modest houses, no matter how dramatically sited.

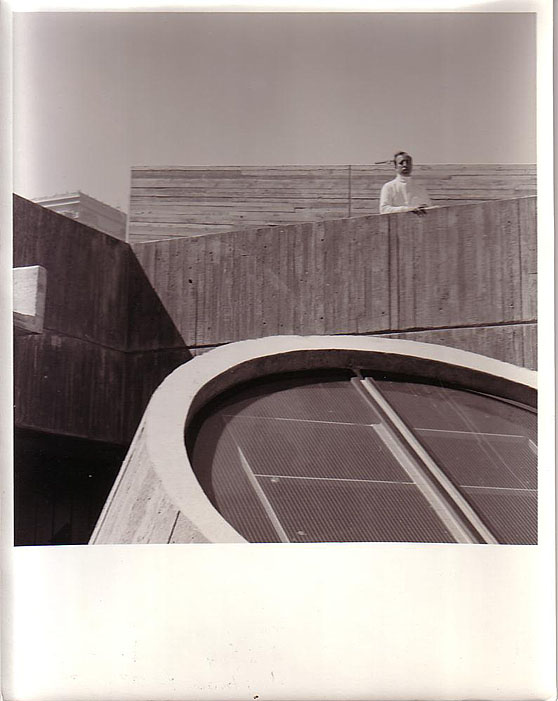

San Francisco Art Institute – Considered Intervention

This building, which put Keatinge-Clay on the map, underwent extensive new master planning, a series of code compliance renovations, and modest additions within and around Keatinge-Clay’s addition in the early 1990s. The vast majority of these operations occur within the loft-like environment of the studio box. As such, the flexibility of the building architecture accommodates these changes without great difficulty. The overall building remains much as it was the day it opened in 1971, a bright and vibrant location in the city. The most problematic addition is a computer lab in the space beneath the auditorium cantilever, which changes significantly the spatial understanding of the terrace level, while at the same time infilling clerestory glazing that admitted light into the painting studios below.

French Medical Center – Erosion

A three building master plan between 5th and 6th Avenues at Geary Street in San Francisco resulted in two completed buildings: one, the descendant of Corbusian housing typologies, the other a descendant of a Miesian office building. Both were rendered in exposed concrete. Like the Great Western Savings and Loan, these buildings have been painted and had their windows tinted. The residential building is pending an imminent renovation.

Camino Alto Medical Center – Stasis by Apathy

Ender Medical Building – Stasis by Obscurity

Both of these buildings are modest office projects that are contemporaries of the Northridge building. Unlike Northridge, however, they remain virtually unchanged, due in large measure to the anonymity of both their location and the reticence of their architectural language. While the condition of these two buildings is notable for its purity, their architectural humility speaks only softly of the pedigree of their author.

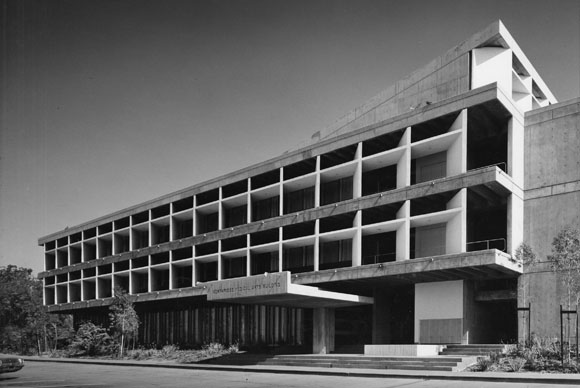

San Francisco State University Student Union – Missed Opportunities

SFSU recently completed a significant third floor addition to Keatinge-Clay’s final building at the center of the campus. The authors of the addition were careful to graft an identifiable, architecturally “distinct” intervention to the rooftop level; the addition, however, seems to be characterized by a vocabulary whose inflection and timbre speak more to a high school in Diamond Bar than to a unique work of American architecture synthesizing a Wrightian plan with Corbusian elevations. A new plaza on the quadrangle side provides an organized, if modest, place for public gathering.

Author Eric R. Keune, AIA, received dual Bachelor degrees in Architecture and Architectural History from Cornell University, where he was the recipient of the Eidlitz traveling fellowship. Subsequently he received a Master of Architecture degree from Harvard University. Licensed in the State of California, he is now an Associate in the San Francisco Office of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, LLP. He is the author of a monograph entitled Paffard Keatinge-Clay Modern Architect(ure)/Modern Master(s) published by Southern California Institute of Architecture Press in 2006.

Originally published 3rd quarter 2006 in arcCA 06.3, “Preserving Modernism.”