It seems worth asking: How far under the radar can you fly and still make an admirable building?

William Wurster’s first published building, the lovely farmhouse near Santa Cruz, was designed for Sadie Gregory, who had been Thorstein Veblen’s research assistant at the University of Chicago; and Veblen, you will recall, coined the term “conspicuous consumption” in his 1899 Theory of the Leisure Class. Building during the depression years, Gregory and her circle, who came to form the core of Wurster’s residential clientele, were determined not to be conspicuous. Wurster was the perfect architect for them. As his wife, the urbanist Catherine Bauer, observed, “No one can make an $80,000 house look like a $10,000 house like Bill Wurster.”

Wurster was not alone, however. Together with Gardner Dailey, John Dinwiddie, and others, he established a phase of Bay Area architecture whose chief distinction is that it is now almost invisible. It wasn’t quite so invisible at the time; its camouflage is largely a result of its having spawned a context that looks like it, rather than the other way around. And this Bay Area modernism was not “under the radar,” but was in fact the most widely published American work of its day.

Still, it was an architecture that sought anonymity, and that modest approach toward building has characterized some of the best building in the Bay Area, which is one reason that San Francisco has, until very recently, been such a sleeper, architecture-wise. Now, with the arrival of the international stars, we blush to think what will become of our modesty.

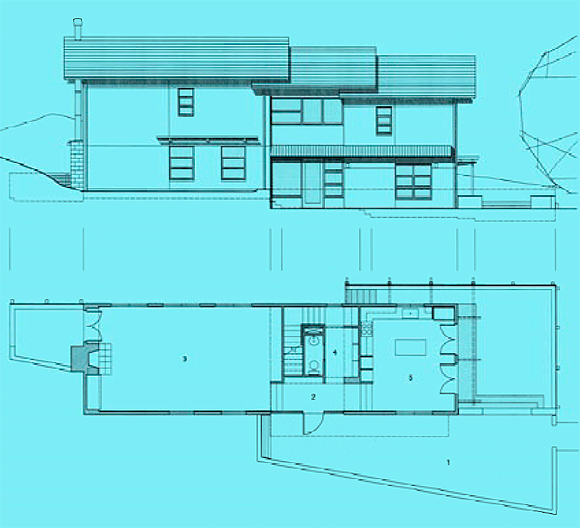

And yet this Bay Area tradition continues, identified not by a style, but by an attitude. The Sharafian Residence, by Nick Noyes Architecture, is an example. Its conception is thoroughly modern: a straightforward plan, with alternating served and service zones. The material nature of its construction is subtly but clearly expressed. Its protective coloring, however, is Tuscan, rather a no-no in our day, when buildings are expected not to reminisce (except, perhaps, about the Weissenhofsiedlung.) There is nothing conspicuously innovative about it—though it employs passive solar principles that, as the architect says, “are ideally suited to the temperate climate of the Lafayette hills.” To make matters worse, it quietly defies what Donlyn Lyndon has referred to as “the dumbfoundingly stupid idea that roofs with shapes aren’t modern.” Modest, allusive, gabled: to the fashion-forward, this well-made building is nearly unpublishable—which is why we’re pleased to present it here.

Which is not to say that the next building we feature will not be thoroughly bizarre. If you’ve ever seen a stealth bomber passing silently over Fisherman’s Wharf during Fleet Week, you know there’s more than one way to fly under the radar.

Author Tim Culvahouse, AIA, is editor of arcCA.

Photos by J. D. Peterson.

Originally published 2nd quarter 2002, in arcCA 02.2, “Citizen Architects.”