If you stood in the middle of an island in the Sacramento/San Joaquin Delta, where the Great Central Valley of California drains into San Francisco Bay, you might not know that you were twenty feet below sea level. You might not realize that the rational agricultural geometry around you ended abruptly at the meandering river on the island’s edge. You might not understand that the ditches running through the fields were dug for drainage rather than irrigation. You might not think that there was anything strange about the Delta until you saw an ocean-going freighter cruise by in the distance, eighty miles from the Golden Gate and fifteen feet above your head. If you climbed to the top of the levee that separates the island from the river, where you could see land and water together, you might wonder how the landscape became such a paradox. And if you didn’t know that a large part of the water in the river was flowing not toward the Pacific Ocean but toward farms in the Central Valley and kitchen sinks in Los Angeles, you might wonder why such a paradox is sustained.

In 1850 the Delta was still wild. The largest tidal estuary on the West Coast and the endpoint of California’s two great rivers, it consisted of low-lying islands among the distributary channels of the Sacramento and the San Joaquin. It was a landscape in flux: river channels moved, water levels varied, and land flooded and dried out with changes in the sea- sons and the tides. Its current history began that year, when Congress passed the Swamp and Overflowed Lands Act. That legislation made marshlands like the Delta available for settlement on the condition that they were reclaimed for agriculture.

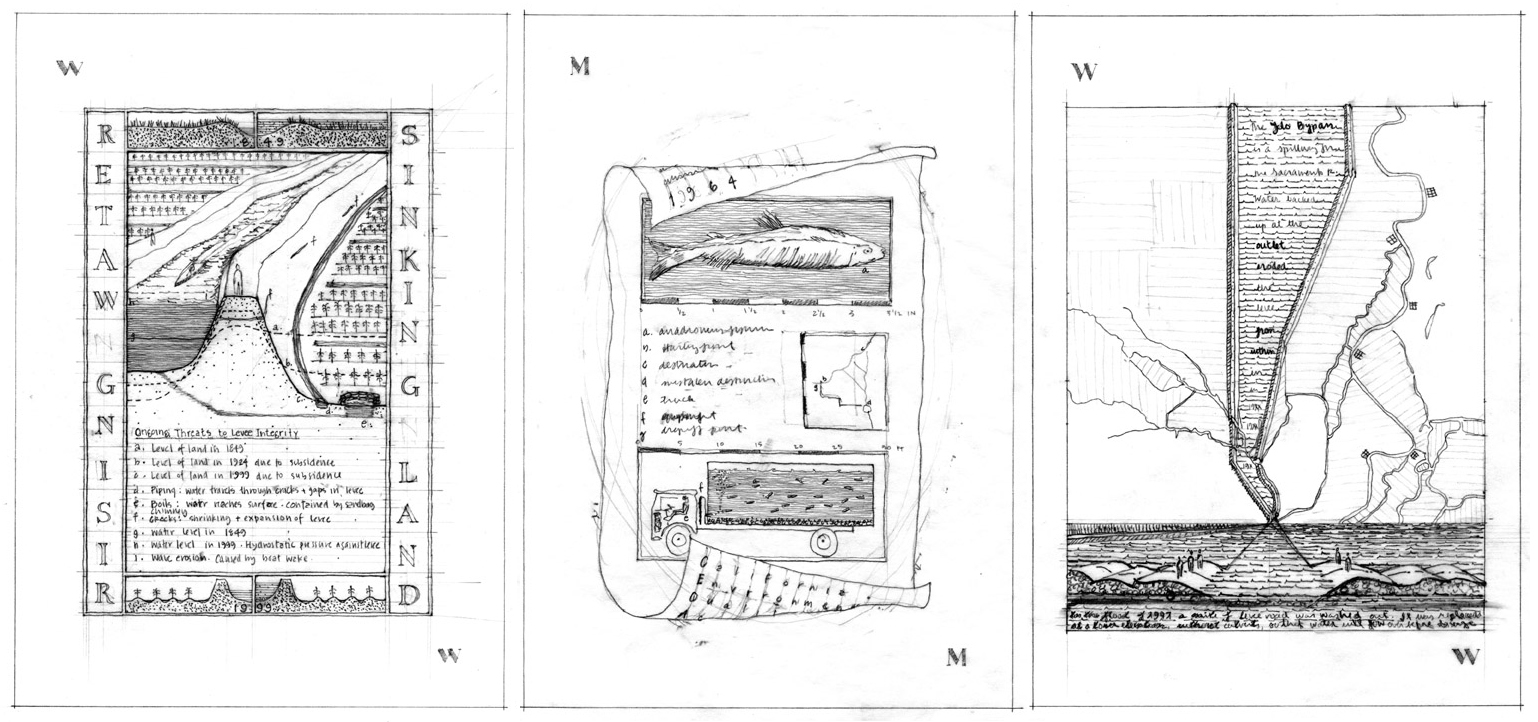

Agriculture required infrastructure. The Delta’s settlers built small levees around the islands to stop seasonal flooding, and they drained and cultivated the interiors. These interventions had an unexpected consequence: the land began to sink. The region’s peat soils were extremely fertile, but they were unstable. The peat oxidized when tilling exposed it to air, and it blew away as it dried out. The ground began to subside at a rate of several inches a year.

To compensate, farmers made their levees higher. This, too, had an unanticipated result: the rivers began to rise. Because they eliminated the flood plain, the levees increased the volume of water in the river channels during the rainy season. The channels began to silt up with the alluvial sediment that had formerly replenished the surface of the islands, and the water level rose even when the weather was dry. Flooding became a constant threat rather than a seasonal one.

The consequences of infrastructure (and the need for more infrastructure to address them) became more extreme. The land fell so low that groundwater had to be pumped up and out of the fields. Levees, no matter how high, were subject to shrinkage, cracking, and failure due to hydrostatic pressure; they required constant repairs and additions. The cycle of intervention and reaction has become the Delta’s leitmotif. It is endless, and its results are irreversible.

Cultural demands on the landscape have expanded, and so has the infrastructure needed to realize them. Since the Second World War, the Delta has become the centerpiece of the system that delivers water to Southern California. Like the levees that made agriculture possible, the infrastructure that delivers water has had unexpected and devastating consequences. Its implications are bigger because the scope of the new infrastructure is greater; they are more tangled because the contemporary range of intentions for the landscape is more complicated.

The export canals have transformed the meaning of the Delta’s rivers. Before, they served as local transportation infrastructure for farmers and produce; today they are the center of a giant plumbing network that extends for hundreds of miles and serves a distant constituency. The large-scale export of water from the Delta began in 1951, when the Delta-Mendota Canal opened. Funded by the federal government, its purpose was to provide irrigation water for the Central Valley. An ancillary installation, the Delta Cross Channel, carried Sacramento River water to giant pumps that fed the canal. In 1973 the state of California opened another canal, the California Aqueduct, to take water from the Delta to Los Angeles and San Diego. It had its own pumping plant; next to the pumps, a new forebay allowed sediment to settle out of the water before it was sent to the south.

Water export caused unanticipated changes in the Delta’s fluctuating ecology. Sending vast amounts of water to the canals instead of the ocean allowed salt water from San Francisco Bay to migrate upstream. That threatened an old Delta interest, agriculture: salty water in the rivers would produce salty groundwater, and land could quickly become unfit for cultivation.

Beyond that, the force of the pumping changed the direction and quantity of the rivers’ flow significantly enough to confuse the native fish that migrate through the region. Instead of swimming toward the ocean they went into the pumps, and their population began to decline dramatically. That was unacceptable to a newer Delta interest, the environmental movement.

Political pressure developed to reduce the ecological cost of the aqueducts. The California Environmental Quality Act of 1964 made the protection of rare and endangered fish species a condition of water export, and new measures were developed to satisfy the law.

Some of the environmental infrastructure was physical, and some of it might be called behavioral. First, enormous screens were installed to remove fish from the mouth of the pumps. Then, a protocol was developed to identify, count, measure, and record the collected fish; to take them in specially adapted tanker trucks across the Delta to a point just above the mouth of the Sacramento, out of reach of the pumps; and to put them back into the river.

Even this well-organized, highly choreographed strategy has had unexpected consequences, though. The Delta has a large population of striped bass that were introduced for sport fishing. The fish trucks run on a regular schedule, and they always drop the fish at the same place. The prolific, adaptable striped bass wait at the drop-off point for the trucks, and they eat the fish that have just been rescued from the pumps. So far no interventions have been made to address this development: measures that could eliminate the exotic predators would also destroy the native species whose welfare is a legal mandate.

The interest environmentalists have in protecting endangered fish is not exactly the same as the one that farmers have in keeping their land dry, but both goals share an assumption that people can and should determine an agenda for the landscape and a system of infrastructure to carry it out. The difference lies in what’s wanted from the land: in the face of increasing urbanization and overwhelming technology, our society has begun to care about the idea of nature.

This concern has produced the Delta’s latest paradox: new nature. Unlike older conceptions of nature, new nature does not imply freedom from human control. Instead, it offers an image of the Delta’s past: subsided land is taken out of agricultural production and native wetland plants are grown instead.

New nature is closely tied to new infrastructure. Paying for new nature has become a way of buying more water for export. Funding for many of the projects comes from CALFED, a consortium of state and Federal agencies whose contradictory mandate is to meet the increasing demand for water in Southern California and to maintain and enhance environmental quality in the Delta. CALFED is currently studying the purchase of one of the largest new nature projects, which will transform four very low-lying agricultural islands in the middle of the Delta: two will become wetland areas and two will become reservoirs. In addition, new nature is helping to make possible the development of new infrastructure at the Delta’s perimeter. Developers in nearby cities and suburbs can pay for wetlands projects in the Delta to fulfill legal requirements for environmental mitigation.

Ironically, new nature depends completely on the levee system built to overcome wilderness: without the levees, the Delta’s subsided islands would flood. What uncontrolled nature would produce today is a wild inland sea. It is possible to see unmanaged nature in the Delta: it exists at Franks Tract, a former island that was reclaimed for agriculture and cultivated until 1936. That year the levee was breached and the bowl-shaped interior flooded. Because the cost of repairing the breach and pumping the land dry again was prohibitive, the island remained inundated. The wind conditions in that part of the Delta created waves strong enough to erode the levee from inside, where it was not reinforced, and it deteriorated into small fragments overgrown with cattails and tules. The island has become an open lake with enough erosive force to threaten the levees that protect neighboring farmland. Its agricultural past is under water, and the marshy ecosystem that came before it is irrevocably lost.

There is no end game in the Delta. The cost and difficulty of maintaining the region’s infrastructure are only increasing. On the other hand, if the levees fail and the region is inundated, salt water from San Francisco Bay will migrate upstream. Giving up the struggle would mean losing things that our society wants from the landscape: fertile agricultural land, the remnants of a unique ecosystem, and, not least, the water supply for nearly two thirds of California. Building infrastructure that would guarantee and streamline the export water supply, like a peripheral canal to circumvent the Delta, threatens other uses like agriculture and environmental restoration.

The Delta’s difficult history and uncertain future rest on the same paradox: infrastructure assumes stasis, and the Delta is a system in constant flux. Instead of stopping the natural processes at work there, engineering has made them harder to predict. Trying to control dynamic situations has simply produced new dynamic situations. This messiness is what makes the Delta compelling. It shows us the possibilities and the limits of inhabiting, transforming, and using the landscape.

Author and landscape architect Jane Wolff is an assistant professor of landscape architecture at Ohio State University. As a Fulbright Scholar and Charles Eliot Traveling Fellow, she has studied the history, methods, and cultural implications of land reclamation in the Netherlands, research that provides a framework for her investigations of the San Joaquin and Sacramento River Delta. In her Delta Primer: a Field Guide to the California Delta (William Stout Publishers, 2003), she developed methods that designers can use to encourage and frame public debate about contested landscapes. The drawings above are studies for Delta Primer.

Originally published 4th quarter 2001, in arcCA 01.4, “H2O CA.” Re-released in arcCA DIGEST Season 11, “The Valley.”