In the opening pages of The Archeology of Knowledge, French theorist Michel Foucault remarks: “History is that which transforms documents into monuments.” Photographs of buildings have certainly shared such a destiny in the twentieth century. The proliferation and circulation of images in publications have increased exponentially, following the pace of technological advancements in photographic reproduction. The introduction of color in the forties was a definite turning point in the effectiveness of the medium to lure readers into a world half reality, half imagination. Just as drawings were the vehicles of architectural ideas from the invention of printing up to the late nineteenth century, in more recent times pictures have taken on a primary role in delivering design content to readers.

Virtually all publications on architecture include photographic material. Yet a finite number of images has exerted an almost hypnotic power in the field, to the point that the chapters of the Modern Movement are nearly inseparable from the photographic record of the buildings being discussed. These pictures keep coming back over and over again with relentless assertiveness, becoming discursive units in a coherent system of visual references. This disciplinary framework is handed down from generation to generation, locking our understanding of an historical period into a unifying narrative that allows no interpretative change, resisting potentially revisionist investigations of the past.

A precondition for this pattern is that the photograph be perfectly preserved in a processed archive, accessible to all researchers interested in acquiring the copyright, and readily available to publishers. In the United States, some photographic archives are particularly well kept and organized. They are constant sources of visual material for trade publishers eager to make coffee table best-sellers, as well as for academic presses reinforcing or challenging the canons of architectural history. The names linked to archives associated with what is today known as Mid-Century Modern are widely known in and out of the country: Julius Shulman, Ezra Stoller, and the Hedrich-Blessing brothers, followed closely by figures like Balthazar Korab, Joseph Molitor, Roger Sturtevant, Morley Baer, and Samuel Gottscho and William Schleisner, among others.

When drawing pictorial material from these archives to make cases in architectural history, scholars consistently reinsert into the field a large, yet finite and predictable, body of images on which studies of modern living in corporate and suburban America have been polarized. We still see today the same image of the TWA terminal at JFK in New York that Stoller took in the fifties, despite the fact that several architectural photographers had taken pictures of that building. The snapshots Molitor created of the work of Paul Rudolph are what the audience is constantly exposed to, regardless of other compelling images of the same projects. California modernism is still equated with the artistry of Shulman, although other photographers were actively engaged in covering the Southern California territory. These pictorial documents are the monuments of our modernity.

Yet, looking more closely at the publications of the post-war period, one notices a far more diversified representation of architects and their buildings. Generous coverage (in color) of projects and architects mostly unknown to us today wallpaper the magazines and newspapers of that time, together with the occasional “classic.” The names of the architectural photographers are often just as obscure or at best moderately known: Robert Wenkam in Hawaii, Robert Cleveland in Los Angeles, Fred Lyon in San Francisco, to name a few. We can find their work featured in magazines such as Sunset, The Architectural Forum, Progressive Architecture, and Time and be captured by the striking effects of some of their compositions. Yet we see no trace of their creativity in contemporary output. How so?

The disappearance of particular icons from architectural culture, and—conversely—the constant reinforcement of other icons, simply because the negatives are available, is a phenomenon worthwhile reflecting upon. Maynard Parker’s archive is a case in point. Parker, a Los Angeles-based architectural photographer now deceased, was widely known during his lifetime, partially through his association with the magazine House Beautiful. His work encompasses images of the architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, Harwell Hamilton Harris, and Anshen+Allen, among many others. In the course of his career, he generated 80,000 negatives, which are currently stored in the Huntington Library in San Marino, California. The bulk of the collection, however, still needs to be processed. The fraction that is organized is arranged by homeowner or project name, simply because Parker usually included this information (rather than architect’s name) on the outside of the envelope. Yet there are currently no indexes or logbooks for the collection. The Parker Collection contains both black and white negatives and color transparencies, but many of the transparencies have color shifted due to the hostile environment in which they were housed—Parker’s uninsulated attic—for many years. The nitrate negatives, being an unstable medium to begin with, are in no better condition.

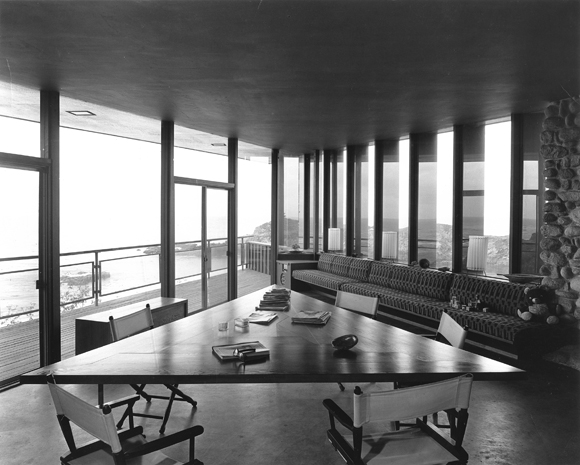

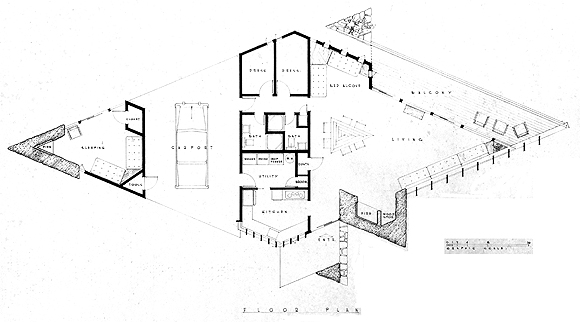

It follows that today the work of Maynard Parker is practically unknown to the younger readership, mainly because it is not amenable for reproduction. The fact that the archive is unprocessed and many of the negatives are damaged—some beyond restoration—makes it virtually impossible for publishers to reinsert the architecture he photographed in to the books that keep the memory of mid-century modern alive. We can’t bring back to our contemporary consciousness, for example, the Emmons House in Carmel by Anshen+Allen, designed in the early fifties and recipient of numerous awards, simply because the negatives are not there. And yet the project was hailed as a sensitive insertion of modernity in the gentle landscape of the coastal town. The same goes for the images Parker took of the Morris Shop in San Francisco by Frank Lloyd Wright, where he was able to frame in one illustration the entire spiral ramp leading to the mezzanine. Not a trace of an indoor-outdoor relationship he captured in a house credited to Harwell Hamilton Harris, published in a book called American Building by James Marston Fitch. None of the surprises that that archive could yield if it were processed and its negatives were in fine state can ever reach us.

Another instance of uncelebrated California Modernism is an historical “victim” of archival loss. The Tamalpais Pavilion by British, but San Francisco-based, architect Paffard Keating Clay, designed and built in the mid-sixties in Marin County, is lost in its documentation. Former architectural photographer Robert Brandais, who did the assignment for the project, has no recollection of where the negatives might be. No archive of the architect is anywhere to be found. The building apparently has been demolished. Yet this project was celebrated in the press for its adventurous use of concrete and was shown in the former San Francisco Museum of Art (now the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art) in an exhibit organized by David Gebhard on recent California Architecture. Moreover, Paffard Keating Clay had the credentials to be tenured as a lasting figure of provocative modernism, having worked for Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright, and SOM San Francisco, while also having married the daughter of architectural historian Sigfried Giedion. With any images of the work lost, with no architect to contact, no drawing to refer to, and no building to visit, the link with posterity has been irreversibly broken.

These are examples of what I will call “silent archives.” They are either tangible—as in the case of Maynard Parker, where the collection is there but is not processed—or intangible—as in the case of Paffard Keating Clay, where no documents are available—in either case, instances of an entity that cannot speak to us. As opposed to active archives, where data can be easily retrieved and photographs function as both records and salable commodities, silent archives are bare trails of bread crumbs, hinting at a reality we can never really reach.

Such is also the destiny of the late Gordon Drake, a promising architect who started his career in Los Angeles and moved to San Francisco in the early fifties. Before his premature death in a skiing accident at age 34, he built several significant buildings. Architectural photographer Morley Baer depicted all the work he did in San Francisco and Carmel. And yet, the Baer archive does not list them in its logbook. As a result, the townhouse Drake designed in the city with landscape architect Douglas Baylis, for instance, cannot be republished, not because the building wasn’t there, but simply because neither transparencies nor negatives or prints can be found.

One final example: Anshen+Allen designed the Moore House in Carmel in 1951. Acclaimed in the national and international press, the building was photographed only by photographer George Cain, a character nowhere to be found. Since the record was not readily available, the Moore house could not be examined or shown for renewed appraisal. Only recently did someone in the Anshen+Allen firm find the pictures of this house in a box, by sheer chance.

These are merely a few instances of the interdependency between architecture and its own record. In order to exist beyond the life of the building, to be transmitted to those yet to come, for the unborn eyes of our future architect colleagues, architecture has to acquire a more ephemeral, yet long-lasting format: the photograph and—equally important—its accessibility in the future.

Author Pierluigi Serraino, Assoc. AIA, is an Italian architect and a Ph.D. candidate in Design Theories and Methods in the College of Environmental Design at UC Berkeley. Author of History of Form*z (Birkhauser, 2002) and Modernism Rediscovered (Taschen, 2000), his writings and projects have been published nationally and internationally. Serraino graduated from the School of Architecture of the University of Rome ‘La Sapienza,’ and earned his M.Arch. at SCI-Arc in Los Angeles and his M.A. in History and Theory at UCLA. His research interests include collaborative multidisciplinary design, professional practice, information management systems in the workplace, and architectural photography. He has practiced architecture in Italy, France and in the United States. Currently he is project designer at Anshen+Allen in San Francisco.

Originally published 3rd quarter 2004 in arcCA 04.3, “Photo Finish.”