In 2005, the journal Places published a series of three articles debating the siting of the newest campus of the University of California at Merced. This series was collected for parallel publication in arcCA 05.4, “Sustain Ability,” by permission of Places.

NEW CAMPUSES FOR NEW COMMUNITIES: THE UNIVERSITY AND EXURBIA

Richard Bender and John Parman

Richard Bender is an Emeritus Professor and former Dean of the College of Environmental Design at the University of California, Berkeley. He founded the Campus Planning Study Group there in the mid-1980s and has consulted with U.S. and international universities and colleges on their development. John Parman has a particular interest in how urbanity is supported in modern towns and cities. He writes for AIA San Francisco’s _LINE and other publications.

Universities and colleges can be great forces for urbanity in their communities (and vice versa). Just how this potential is integrated into a community, however, has been the subject of various interpretations through history. Today, in America, there is a tendency to think that the university campus must be a place apart. Likewise, on campus, there is a tendency among university administrators to think that every new academic or institutional “need” must be translated into a new building campaign.

There are other options. While models like Jefferson’s University of Virginia and venerable Ivy League campuses still shape our sense of an appropriate setting for academic life, an even older root—going back to Bologna, Padua, and Paris—situates the academy within the polis and makes it an integral part of everyday life. The urbanity of this model reflects the historic tendency of towns and cities to mix uses in a fine-grained way that creates and enlivens culture as well as stimulates the local economy. For many such institutions, a more intensive mix of uses may also reflect financial necessity, leading them to seek partners in their communities with whom to integrate facilities.

The need for alternatives to a territorial, facilities-oriented approach to campus planning was brought home to us in the late 1990s with the financial collapse of the American Center in Paris. Following the completion of a magnificent building designed by Frank Gehry, its director publicly reflected on how he had thought he was building a $40-million asset, when in fact he had built a $6-million-a-year liability.

Universities have learned from their own past to the extent that they are developing more flexible buildings today and often forming new partnerships to share the cost with others, including developers. Urban universities are also increasingly looking beyond their own campus boundaries to grow. Arizona State University, for example, is expanding across metropolitan Phoenix, while Harvard is shifting its science and technology faculties to a new campus across the Charles River. Bard College has established a study and research center in Manhattan, just as ASU, with its main campus in Tempe, is moving into downtown Phoenix. All of these developments point to a recognition that these institutions realize their futures lie at least partly in looking beyond traditional campus boundaries, integrating university programs with those of the city at large.

Such a rethinking of seemingly fundamental tenets of American campus design is particularly relevant today as “learning” becomes a lifelong, year-round pursuit. Postsecondary education is now a necessary accompaniment of adult life, enabling people to ramp up skills, get needed credentials, and finally move from work to the rest of life. Given this, the idea of building a traditional university or college campus may be more and more of a distraction from what real investment in higher education is coming to mean.

The Rise of Exurbia

A rethinking of what a campus is may prove especially beneficial in “exurbia.” This is the name recently given to sprawling new communities like Mesa, Arizona, which are frequently home to as many people as older cities like St. Louis. Such locales evince all the forms of the twentieth-century American suburb, but without any sense of being tied to an original center. They are a logical next step from what Joel Kotkin and others have noted about U.S. demography: that since 1960, more than 90 percent of all population growth in America’s metropolitan areas has taken place in suburbia.1

Another social critic, David Brooks, attributes the rightward shift in American politics to exurbia, which he contends is not simply an “opting out” of the city, but also a more utopian impulse to reinvent the city, in the tradition of new towns from Ebenezer Howard forward.2

Exurbia may only be passing through a suburban stage on the way to becoming a new metropolis. But universities and colleges may contribute to this transition by helping to give it much-needed cultural and civic life.

Missed Opportunity

Despite the potential benefits that a rethinking of the relation between campus and city might entail, most large university systems continue to build according to old models. A good example is the construction of a tenth campus of the University of California, now underway in Merced. Merced is one of a chain of towns and small cities extending south from Sacramento to Bakersfield in the state’s vast Central Valley. This formerly agricultural area is today developing according to the classic exurban scenario, and all indications are that it will become California’s third megalopolis by 2050. As a result of this growth, the population of formerly sleepy Merced is expected to rise to 200,000 in the next forty years.

As the setting for a new urban agglomeration, the Central Valley has several things going for it. Older patterns of infrastructure and commerce already link its towns with a major highway (California 99) and several north-south rail lines, one of which the state may rebuild to accommodate high-speed passenger service. Furthermore, its older town centers, largely developed in the early twentieth century, offer attractive grids of tree-lined residential streets and tidy, if underutilized, commercial cores. Yet, instead of seizing on the potential offered by this pattern of existing settlement, with its transportation and communications infrastructure already in place, UC chose to locate its new campus (for an eventual population of some 30,000 students) on open ranchland some six miles out of town.

The University of California has a history of locating its new campuses on open land. Its oldest campus, at Berkeley, was founded when the university moved out of its original headquarters in downtown Oakland. Built on grazing land in a town that was mostly a summer refuge for San Franciscans, UC Berkeley was eventually surrounded by a new city that grew up around it.

The real antecedents for UC Merced are, however, the UC campuses developed in the 1950s and 1960s, like Santa Cruz and San Diego. Both were organized around separate, inward-looking academic/residential colleges. Both were also deliberately held at a distance from surrounding cities, a strategy that has proved especially problematic at Santa Cruz, where it has largely eliminated any possibility to share facilities with the larger community.

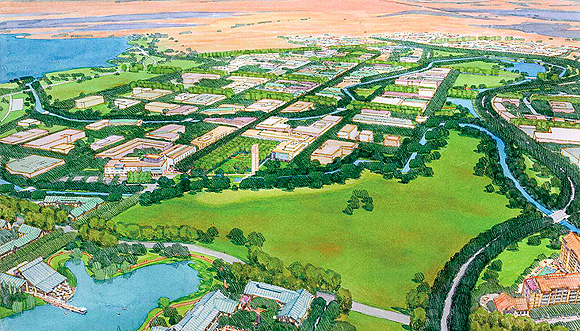

The design of the Merced campus, following a skillful overall design by a team led by John Kriken of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, San Francisco, largely adheres to this traditional territorial model.3 It proposes a tree-lined street grid, recognizing this as a pattern of Central Valley towns, as well as an effective way to make a compact and urbane campus that can mitigate the area’s extremely hot summers and cold, windy winters. But at Merced the distance between the existing town and the new camp u s appears to impede initial opportunities for synergy between the campus and the Merced community. With its implications for extended infrastructure, travel time, energy use, and pollution, six miles is just too far.

If planners had looked further back, past UC’s suburban precedents of the 1950s and ‘60s, they might have discovered models that specifically anticipated ways that a campus and a community might better evolve together. But this would undoubtedly have involved building closer to town, or even in town, and the political leaders of the multi-campus UC system did not want to take on the problem of assembling land in an area where patterns of development had already been established. Instead, they opted to site the new campus on “empty,” supposedly trouble-free, land that they were able to obtain relatively easily. As it has turned out, however, environmental problems related to the presence of vernal pools and other environmental constraints have now contributed to a nearly decade-long delay in construction.

Today they have also led to the first phase of the campus being located on an adjoining former golf course, an area not included in its original 2001 master plan. One other obvious problem with the chosen site was the lack of any surrounding amenities. To make up for this, however, a new General Plan for the City of Merced, produced in parallel with that for the campus, calls for a series of planned residential developments between the existing town and the site of the campus, anchored by a “town center”—a private shopping area.

Meanwhile, although the opportunity was constantly pointed out during the planning process, the town and the university both failed to engage each other and find concrete ways they could benefit from the other’s presence. Libraries, museums, medical facilities, playfields, stadiums, and even things like utilities and police and fire services were all potential candidates for joint development. By banking land for future growth, they could both have gained from the rise in Merced land values.

From a regional standpoint, the decision was similarly flawed. If a site had been selected that was more closely related to Highway 99 and the north-south rail corridors that historically linked the Central Valley towns, it might have better fulfilled UC Merced’s potential to serve the whole region, not just one part of it. Indeed, in the run-up to the opening of the new campus, the university has opened academic sub-centers in other valley towns and cities, and it has become clear that many students will commute from their homes up and down the valley. Given such an existing pattern, it is ironic that the final decision focuses all the state’s resources in one out-of-the-way location.

An American “New Town”?

Ironically, UC Davis—the one campus that most obviously reflects the University of California’s land-grant heritage (for years, one of its great strengths was agriculture and natural resources-related research)—comes closest to being the model that might have provided the most sensible basis for a design that could have served both UC Merced and the larger Central Valley community.

Adjacent to a rail corridor that links the Bay Area to Sacramento, Davis also falls within a fast-developing “exurban” corridor—one that extends east along I-80 from Vallejo to Sacramento, and beyond to Roseville (along I-80) and Placerville (along US50). Like the Merced campus, the Davis campus was originally laid out on a grid pattern; unlike Merced, the Davis campus was conceived as a loose extension of the adjacent town. Even the creek that runs through it helps connect them.

The Davis example was not the only alternative that could have been seized upon as a precedent. Before the Merced site was chosen, the larger Central Valley city of Fresno had proposed that the core of the new campus occupy a section of its early-twentieth- century downtown, the Fourth Street Mall. This area had been a center of prosperity in the pre-freeway era, but for many years it had been bypassed, as suburban development spread to the northeast. In addition to many underutilized properties, it offered good proximity to an existing train station and good access from Highway 99.

Those with experience of European campuses might recognize the Bologna model in such a plan to re-inhabit an older urban area. In the US, the benefits of such a strategy have also been reaped in Manhattan, where NYU has for years renovated industrial lofts as classrooms and student residences, and in a broader sense has adapted itself to the urban fabric of that city. DePaul has also followed this strategy in Chicago’s Loop. In other historic European towns like Siena, a further benefit is that the university can play the role of custodian of important elements of its historic fabric, while locating other parts of its program, like laboratories and athletic facilities, outside the town’s historic zone.

Looking farther afield, it is possible to see an even more relevant example. In the 1960s, about the same time that UC Santa Cruz was being developed, the French new town of Cergy-Pontoise was being created outside of Paris. The town was to incorporate several existing villages, but universities were planned to be among its earliest new elements. Today these institutions include ESSEC, one of the leading business and management schools in Europe. A technical university was also created, and it now supports many of the high-tech companies that have relocated to the region. They were initially brought in as a way to provide jobs that would induce people to move there or “reverse commute” from central Paris—part of a regional strategy that also saw the development of the RER line passing through Paris to connect new towns to Central Paris, Orly, and Charles de Gaulle International Airport.

Like Merced, Cergy-Pontoise is located on the fringe of a major urban center. The great amount of farmland that surrounds it and its proximity to the large Vexin regional park are also similar to the position of Merced—also surrounded by farmland, and which often refers to itself as a gateway to nearby recreation areas in the Sierra foothills and Yosemite National Park.

The success of these planning initiatives forty years ago has now become fully evident.4 Cergy-Pontoise today has a population of close to 200,000 people, along with 25,000 university students. Moreover, the recent development of high-speed rail service to the UK has situated Cergy-Pontoise along a linear network of towns that are becoming proximate to London as well as Paris, underscoring its role in an expanded regional economy. Businesses in the town are already connected to this corridor’s fiber-optic line, which runs along the National Highway right-of-way next to the technical university at Cergy-Pontoise.

Evolving Exurbia

Unlike the development of most new US communities, of course, the building of Cergy-Pontoise involved a major initial public investment in physical and social infrastructure. Indeed, part of the goal of the new-town effort around Paris was to shift the center of development pressure away from its historic center.

In comparison to the French model, such peripheral development in the U.S. usually emerges “in reverse.” The private sector usually leads the way—with low-density projects coming first, followed typically by privately developed shopping malls. If there is an existing town, as there is in Merced, it often must compete with—and may ultimately be undermined by—this piecemeal development. The choice of where to locate a major public university could, however, have been regarded as a strategic intervention to encourage a more sensible and coherent (and less costly and destructive) pattern of development. While the planning of the UC Merced campus aimed within its own boundaries for this kind of coherence, it missed it entirely in terms of what the campus could do for Merced, and vice versa. This was equally true for the Merced General Plan—which suggests that both entities failed to understand the exurban phenomenon.

Exurbia has tended to grow on an ad-hoc basis as an agglomeration of “planned communities” that are relatively low density and car dependent, with few public or community spaces. Schools and churches are often the first civic buildings, and cultural life often begins with them, along with shopping and movies. In this context, a university or college campus could help provide the missing elements—the “collegial” and cultural settings that support the civic and cultural life of the community—along with opportunities for education and training. One example of such a relationship can be found in the community of Cypress-Fairchild (actually a school district) outside Houston, where the local government partnered with a community-college district to develop a campus whose civic, cultural, learning, and recreational facilities serve a population that runs the gamut from toddlers (and their moms) to younger postsecondary students, adult workers, and the retirees who enroll in its Senior Academy—one of its fastest growing programs.

One characteristic of these exurban campuses is the way they seek to capitalize on the interplay between learning and a broader community of learners—and vice versa. Another is how their physical form evolves in relation to their communities. In this sense, Cy-Fair College is both a college, albeit with a broader constituency than most universities, and a town center.

Need for Stewardship

The last point reflects on what should be an important concern for campus planners generally: that, in developing a university or college in an exurban context, it may be particularly important to tailor development to where a community is in its lifecycle. Following such a tenet, what would have made more sense in a place like Merced than to utilize already existing, undervalued resources as a way to build together toward a common future?

In fifty years, UC Merced may come to seem a part of its community. By then, the population of the town may, in classic exurban style, “fill in” the agricultural land between the new campus and the existing town. It may even grow right up to its gates, so to speak, and create the same problems of boundaries and edges that cause such difficulties between other UC campuses and their surrounding neighborhoods. But until then the town will not gain much from the presence of the campus, and the campus will not gain much from the town. The region, similarly, will be only poorly served.

This may be the most salient point today—that towns or cities and their colleges or universities need to see each other as partners. Both need to share a sense of stewardship. As Frederic Law Olmsted put it, a campus needs to provide settings for learning for its students that reflect “the work of disciplined mind.” In exurbia, especially early on in its development, doing so may be particularly valuable. Ebenezer Howard, who we might think of as one of the fathers of exurbia, saw new towns as an opportunity to build a new civilization. In a real sense, the campuses of the new exurban universities and colleges, UC Merced among them, are opportunities to bring the benefits of the city to areas that are ready to embrace them, but in a new form.

Notes

- Joel Kotkin’s books include The New Geography: How the Digital Revolution is Reshaping the American Landscape (New York; Random House, 2000). His The City: A Global History will be published in April by Modern Library Chronicles.

- David Brooks, “Take a Ride to Exurbia,” The New York Times, November 9, 2004.

- John Lund Kriken, “Principles of Campus Master Planning,” Planning for Higher Education, July-August 2004; and University of California Office of the President, Long Range Development Plan: The University of California, Merced, Public Draft, August 2001.

- Bertrand Warnier, “Cergy-Pontoise: Du Projet à la Realité,” Atlas Commente (Heyden, Belgium: Pierre Mardaga Editions, 2004).

UC MERCED—TIME WILL TELL

Christopher Adams and John L. Kriken

Christopher Adams was Campus Planner for UC Merced from 1998-2003 and served on the staff that advised the UC Regents on selection of the site. Prior to that time, he was Director of Long-Range Planning for the entire UC system. John L. Kriken, FAIA, AICP, is a Consulting Partner at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill LLP, San Francisco. His work, during many years of distinguished practice, has ranged from regional policy and the structure of cities to the detailed design of neighborhoods, streets, and public spaces.

As the campus planner and lead campus design consultant for the new University of California, Merced, we wish to comment on the Spring 2005 article “New Campuses for New Communities: The University and Exurbia,” by Richard Bender and John Parman (Places, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 54-59). Among other things, this article dismisses the idea of a campus as “more and more of a distraction to what real investment in higher education is coming to mean.” Such provocative questioning is an important aspect of our profession, and, contrary to some of their assertions, the new UC Merced campus reflects this kind of investigation.

Contrary to Bender and Parman’s argument about the changing needs of university campus design, we believe that a UC campus remains a distinct and single place, in the sense described by Frances Halsband in the same issue. The University of California has a basic mission in the state for research and historically has served as the primary public institution for residentially focused undergraduate education. A UC campus is more than individual buildings to be inserted into the fabric of a town; it requires quasi-industrial districts for research, large playing fields, and significant land reserves for the housing of students and faculty.

The program for UC Merced was based on a study of the space requirements of public and private research universities throughout the United States. At such institutions, academic space needs are a function of number of faculty, not students. In converting space needs into land coverage, we considered elevator demand at class changes; building and safety codes, particularly for laboratories; and the surcharge for remodeling high-rise spaces, all of which led us to mid-rise coverage. Because a university is always changing, we provided land for construction staging at all levels of growth. Our observation of UC campuses over the last half century led us to provide generous reserves for faculty housing to allow Merced to remain competitive in recruiting faculty, regardless of the cost of housing in the adjacent community. Finally, parking demand, even at campuses with good public transportation, led us to provide realistic amounts of space for surface parking and eventually for parking structures. (For example, UC Berkeley is considering increasing its parking from approximately 7,700 spaces to 9,000, despite its location on a BART line and at the confluence of a number of bus lines.) The resulting total land area requirements were beyond what any city in California’s San Joaquin Valley could accommodate.

In proposing the integration of the new campus into the core of Merced, Bender and Parman make significant assumptions about the city’s eagerness to welcome the University with its power to reshape the community in pursuit of its academic mission. This proposal also assumes that the University has the administrative and financial resources to acquire the hundreds of separately owned parcels that the new campus would ultimately require. As Halsband noted, when faced with a campus pushing outward, “neighborhoods are likely to push back— and often with good reason, since these neighborhoods themselves have evolved into historic districts, with their own memorable and distinctive qualities of space and architecture.” Merced’s older neighborhood, with their tree-shaded street grid, provided us with a model to emulate, not to destroy.

Bender and Parman cite the examples of UC campuses built in the 1960s at Santa Cruz and San Diego, which, we agree, suffer from their degree of separation from their host communities. Instead, we studied UC Davis, Chico State University, and the Claremont Colleges, as well as older East Coast institutions in small cities, to see what worked and what didn’t. From these examples, we learned that a successful town/gown interface requires close and continuous proximity on at least one edge of both the campus and the town and that car and truck traffic should go around, not through, this interface.

Our solution, which was developed in concert with Merced County planners, places the campus at the border of a new community at the edge of the existing city, within a grid of streets—which would organize development of both. A town center, within the county’s plan and also shown in the campus master plan, forms the heart of the interface. Museums, performing arts facilities, and sports venues will be built at this interface, while other university operations, such as the storage of hazardous materials and certain kinds of research, will be located away from the town. Even further away, a reserve for future research facilities—perhaps for something that cannot even be imagined now—is provided. (Who would have imagined a cyclotron when Berkeley was established in 1878?) We planned that traffic would not separate the campus from the adjacent community, but instead would connect to a new loop road around Merced, which had been initiated prior to the decision on campus location.

In the long run (which is the only way to consider a university master plan), we believe that Merced, the campus, and Merced, the town, will develop jointly as a thriving and exciting community. It will take a while (see photo of UCLA in 1930), but we urge Bender and Parman to come back and take a look.

CARING FOR PLACES: QUESTIONING

Donlyn Lyndon, FAIA, editor, Places

Donlyn Lyndon, FAIA, is editor of Places and an Emeritus Professor of Architecture at the University of California, Berkeley.

Opening questions and turning attention are central purposes of our journal. We are concerned with the design of places—with examining decisions that affect the quality of our lives because they change the things that stand around us. The circumstances of daily life, one might say, are always being altered—it’s a fact of life. The days change, the seasons change, the landscape changes, we change; why shouldn’t places change? They should. They will.

How is change directed and by whom? Whom does it affect, and by what values is it measured? There are also questions of what can be done at any given time, and how we can turn attention to strategies for change that bring benefits to many—to the “have nots” as well as the “haves”; to subsequent generations, not only to “nows.” Change may be inexorable, but its nature seldom is.

Places has also sought to be a source of dialogue, and for this reason we initiated our “To Rally Discussion” section. Christopher Adams and John Kriken make good use of this section to question assertions made in our previous issue on “Considering the Place of Campus.” They argue, with care, in favor of decisions made as chief planner and lead design consultant for the new University of California campus at Merced. Many of these are wise decisions, but they are set within a framework that is questionable. Among the premises that can be questioned are the supposition that UC’s presence in the Central Valley needed to take the form of a single, integrated campus, and that its design and construction should follow the dictates of more commercial kinds of development: lowest available land cost, least complicated process, and most predictable result within the boundaries of the contract. More particularly, they argue persuasively for a vision of “town” facing “gown” across a traffic-less boundary. But that town will be of their own making, beyond the reach of the city that currently exists.

Merced, meanwhile, is left to its own inadequate devices as it copes with the influx of traffic, new populations, and its already heavy load of the underemployed and ill-housed. Like the profiteering developers before them, the university has chosen to move out into the farmlands, consume their apparent emptiness, and leave the troublesome city behind. By contrast, Frances Halsband, guest editor of the campus issue, argues that universities could well become the most enlightened developers/redevelopers of our cities. “Their mission statements suggest interest in educating the public (especially state universities!), in advancing knowledge, building on history and culture, and providing a forum for discussion—all good ideas for cities.”

This issue, “Retrofitting Suburbia,” reports on the many ways low-density, existing places are being reconceived to accommodate higher levels of civic amenity, meet the needs of differing populations and interests, and provide more engaging and effective systems of access (like walking). These are projects that seek an appropriate complexity and that chart new territories in areas previously abandoned by the market. They are a small sampling, but a welcome sign of growing interest in working with (rather than stepping away from) the complexities of the existing.

The projects and articles presented here argue vigorously that thoughtful adjustment should be at the center, not the periphery, of our concerns. They also remind us that to retrofit is not only to reinvest, but also to relive the places that we have. They argue implicitly against the incredible misuse of resources that comes from constantly moving into new areas beyond our previous investments, consuming more “empty” land and neglecting what’s left behind. Wasting places is a habit we can no longer afford. Finding opportunity is a skill we must nourish.