I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. — Henry David Thoreau, Walden

High on the hills of Marin County lies a new sacred ground, a sustainable cemetery where one pays a premium to be buried in unencumbered open space—as an act of land preservation—to return to the earth without toxicity and without markers, in a final exchange between man and nature. This ecological participation is an active call to feed the earth, rather than forge a memory within it.

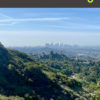

The Bay Area has long been a hotbed of cultural change, from home birthing to the Sierra Club, the Whole Earth Catalog, the progressive Edible Garden project, and most notably the organic movement. If this boomer generation has rewritten the practices of birth, created the eternal summer of love, and brought us back to regional living, why wouldn’t it rewrite the rituals of dying and death? Green burial highlights the debatable loss of our last landscapes, their architecture of remembrance, and the brave act of dying without a trace.

Forever Fernwood is situated in Mill Valley off of Tennessee Valley Road, a provider of green burials since 2004 and the only sustainable burial cemetery in Northern California. The 32-acre parcel backs up on the Golden Gate National Recreation Area and is open to the public 24/7, accessed by car through a limited network of hill roads or via hiking trails connecting the grounds to open space. Because the cemetery has existed since the late 1800s, the traditional section and the natural section lie side by side, yet are two distinct landscapes, one cultivated, requiring irrigation, the other a native landscape that is lush in the spring and brown in the heat of summer. In both sections, every grave is dug by hand to limit noise and disruption of the sloped land.

In 2009, Fernwood opened what is the first green Jewish cemetery in the United States. Situated along its western edge, it is delineated in three sections: orthodox, conservative, and renewal reform. The natural process of green burial is not new to the Jewish traditions, but merely consistent with historic practice; embalming and viewing are avoided, and the body is buried in a plain white shroud, because cremation is against teachings. The belief is that the body is a gift from God, and we should return it as soon as possible and in the best condition possible. Islamic burials are green as well, and, in addition, the body is placed to face Mecca. Christian customs, however, often include a funeral home service, which at the Fernwood facility is more typically used as a memorial rather than as a viewing or wake. All families are offered a virtual memorial, a biographical filmic story created by a partner company.

Our choices in death have a wide range of effects on the earth. Traditional inhumation (to bury or entomb), common to Christian and Anglo traditions, generates the greatest impact to the environment, due to toxic formaldehydes for embalming, and it requires the highest amounts of embedded energy for the production of caskets, concrete or polycarbonate vaults, and foundational headstone footings. These practices sit in contrast to green burials, where the shrouded body is either lowered into the ground by hand with cotton straps or coffined in a pine box, basket, or biodegradable urn. No chemicals are used, and no markers. Bodies are identified only through a GPS grave locator. One caveat is that the baskets available to purchase at Fernwood were made in and shipped from China.

Cremation negatively impacts the atmosphere, both in the amount of energy—natural gas fueling a three- to four-hour process at 1,800 degrees F for one cremation—and in the high level of emissions. The choices here are personal, spiritual, and economic. With green burials, western rituals of internment come full circle. In the wave of living simply, we are merely embracing what was done before—simple living.

The graveyard and cemetery are part of our regional memories as places of remembrance, landscapes of quietude and of retreat from the intensity of urbanity. They offer specificity within the endlessness of the rural landscape and provide sacredness to the profane commercial strip of the American suburb. They are where we have gone to think back and look forward, yet the distinct role of these fields of rest is to put us reverently in the present—and that has been inherently a function of their design and architecture. The historic Pere-Lachaise Cemetery, the largest park in Paris, is precursor to the city public parks of the United States. With its picturesque cobbled streets dense with trees, mausoleums, tombs, and miniature civic structures, it is a fiction of the city at rest, romantically depicting the tragic narrative of mortality and eternity. The Mt. Auburn Cemetery in Watertown, Massachusetts, close to Walden Pond, was established in the 1830s with the rise of American Transcendentalism. It is an Arcadian thereafter, with the traces of human existence set within a lush garden context. The cemetery was a cultivated landscape in the great outdoors, an intersection of leisure and sacred space depicting death in an idealized harmony with the earth and stars beyond. The beginnings of sustainability can be found in Transcendentalism, as well, in the 1836 publication of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Nature, a life philosophy reuniting man with nature.

However, many American cemeteries today have fallen into disrepair, been abandoned, or been completely reinvented. The Ventura Cemetery Memorial Park in Ventura, California, for example, opened in the late 19th century as St. Mary’s Cemetery and later religiously diversified. It fell into disrepair after the last body was buried in 1943. The property was sold to the county in 1964 after many of its headstones were removed. Now renamed Cemetery Park, with a field of unmarked graves, it is presently used for recreation under the shadow of its hidden sacred history. The Bayside/Acacia Cemetery in Queens, New York, is another ruinous beauty. Overgrown with chest-high weeds and filled with overturned headstones, it is a restoration challenge overwhelmed by both vandalism and nature’s aggressive repossession; maintaining the yards for its 35,000 residents has been difficult without a sufficient operating budget. Hollywood Forever, on the other hand, is thriving as a new financial model. Located on 64 acres in Los Angeles, and home to such residents as Cecil B. DeMille, Jayne Mansfield, and Rudolph Valentino, the cemetery is an active tourist and event destination. The grounds have recently been restored, but, more importantly, they have been renewed as public space.

The globalization of our cities and the increasing migration from places of birth have changed the ethos of the cemetery, and a new virtual geography has emerged, with online memorial sites like the worldwidecemetery.com, foreverlifestories.com, and myspaceafter.com. The act of “visiting the grave” and the intimacy of grieving can be experienced from anywhere in the world, and the space between us and our dearly departed have both collapsed and expanded to immeasurable distances. However, within the striking contradiction—the sobering task to sustain our natural world and the unconditional promise of virtual immortality— lies a new question: what role will architecture have, if any, in representing us in death? In the drive to conserve resources, we may choose no longer to leave the evidence of marks on the earth.

Green burials offer new opportunities for merging contemporary sensibilities with environmental politics and artistic expressions; at their highest level of commitment, these sacred acts are basic ecological unions that thrive on pure participation with the earth’s natural systems—without the traces of memory. However, as creators of the built environment, we have every reason to invest in the new architecture of death and its markings. Will future memorials embrace new cultural programs to integrate virtual and visceral geography; explore radical and global visions for cemetery planning; embrace the abstraction and emotion of death; and reclaim the universal desire to be physically remembered in our last exchange with the sublime stretch of the American landscape?

Oddly enough, some partial answers may lie in the past. Monumental acts of funerary architecture, from the indigenous burial mounds in North America to the engineered Egyptian pyramids, speak through impressive reformations of the land itself and interrupt our understanding of the world.

Transfiguration of the land is familiar territory to the land artists of the late 20th century as well; the works of Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria, James Turrell, Maya Lin, Andy Goldsworthy, and Bill Fontana, environmental interventions made with the site’s soil, rock, and water, as well as climatic elements and ambient sounds, bring forth ideas in art and culture through the rearrangement of ordinary ground. Heizer’s Double Negative at Mormon Mesa, Nevada, is a land excavation project of two massive trenches cut in alignment at a great distance from each other to imply an invisible and unattainable connection. Goldsworthy’s Cone sculptures, constructed with small fragments of rock and wood found within a site, are arranged in massive primitive totems to heighten our perceptions of the organic world around us. Turrell’s Roden Crater (not yet completed) centers our physical relationship with the sky. And Bill Fontana’s Sound Island, a live auditory transmission from France’s Normandy coast at the Arc De Triomphe in Paris, provides an unexpected sense of memory. Like the 19th-century picturesque, these works intensify our relationship with nature, yet the artists’ approaches are sensual and existential, driven by process versus product and abstraction versus representation. Might these tactile physical gestures combined with virtual remembrance be our precedents for sacred traces and replace the tombstone tracings of the past?

Author Elizabeth Ranieri, FAIA, LEED AP, is partner at Kuth/Ranieri Architects in San Francisco and Adjunct Professor at the California College of the Arts (CCA).

Originally published 4th quarter 2010, in arcCA 10.4, “Faith & Loss.”