Author’s note: Certain details of the following are tempered by the dimming of the memory of magical events that occurred 40-plus years ago in another country called Youth. The dialogue was reconstructed in Italian and translated.

“Signore Architetto Aidala, welcome please.” He gestured to a chair before the desk. “Bruno has brought to my attention the beautiful drawing you prepared for the presentation. Before we discuss that, I want very much to apologize for not taking the time to welcome you to the studio, but affairs prevailed, unfortunately.”

“I understand, sir, no harm done.”

“Good. Now to the drawing. I would like in the future, should such creative wants descend upon you, and I hope they continue to do so, that they manifest themselves more discreetly. I would beg you to acknowledge who feeds your needs currently and reserve the use of names on drawings to the discretion of the studio director. I can assure you the client would not know nor care who you are even if they discerned your name. Till now we have felt no need for advertisement, since fortunately clients have had no difficulty in finding me. Now then, dear Aidala, to the massing and prospectives (sic),” and then the words I wanted, “I have some thoughts I pray to share with you, since you will continue now solely with Appia Antica.”

With that he picked up a generously fat brush wired to a meter-long handle from among others that lay neatly on his desk. The desk was possibly a 15th- or 16th-century formal dining table bigger than the Fiat I was driving. Hell, it was about the size of the apartment’s kitchen we had recently rented.

The room in which Luigi Moretti had this desk was a high-ceilinged place that, to this impressionable youth, went halfway to heaven. Along the right side were alternating, decoratively stenciled wall panels and draped and shuttered alcove windows that went from sitting height to a few clouds short of the ceiling, stopping at an intricately carved string course. The double entry doors, some three to three-and-a-half meters high, clearly old, wooden, and intricately carved, as well, with scenes I took to be biblical.

The doors were attended to by Bruno, the Major Domo, through whom you had to go to get to them. Bruno was round, with an angelically innocent and open face. His eyes twinkled as though he were perpetually about to smile. He dressed in black (winter) or white (summer) pants and a black, collarless jacket with white pinstripes (winter) and the reverse in summer. Winter or summer, around his neck was a silk foulard that only an Italian or a 9th-century Persian could dream up and wear. I found out in time that he was also Moretti’s bodyguard and driver alternate and was always discreetly packing.

Moretti’s desk was about 8 meters from the entry doors and was approached through a thicket of some 50 easels haphazardly crammed this way and that, holding a changing display of his private collection. His likes and appreciations were as ample, erudite, and catholic as he was. Identified on the first of a few times Bruno let me wander the unoccupied room at leisure were paintings by Guido Reni, Helen Frankenthaler, Giorgio di Chirico, Morandi, a Matisse, a large Sienese predella, and a terra cotta bust of a boy by Houdon, among other equally impressive but unrecognizable works. I had never imagined a “private” collection. Was such discernment and ability to cohere seeming opposites a disposition, a talent, or luck? Whatever, he had it.

It was the first time I had been called to his salotto. I had been working for him for a bit over two months. His studio was housed in the upper two floors of one entire wing of the Palazzo Colonna in Rome.

I was there because in my senior year at U.C. Berkeley I had discovered his Fencing Academy and the “Casa Girasole,” two enormously seminal modern architectural works of pre- and postwar Italy. I had browsed through a few issues of Spazio, then and now perhaps the most important architectural publication of the postwar period, neither completely understanding the Italian nor partially understanding the math. Spazio was never a runway for taste or style. It offered reasoned descriptions of spatial manipulations and disquisitions on their three-dimensional consequences and how they are perceived. The analytical essays were authored by Luigi Moretti.

Arriving in Rome in the very early spring of 1958, I went straight to Moretti’s studio on Via di Sant’Apostoli and applied for a job. I was interviewed by Signora Gardella, the studio director, who was impressed I think by three things: I was the first American to seek work with Moretti, I was technically proficient to a degree young Italian architects and recent graduates at the time were not, and I could sort of speak Italian and therefore communicate with the Boss, who spoke no English. I got the job and four days later sold my wife’s and my return tickets.

Rome was to become home for the next three and a half years.

My acquaintance with Bruno was in hindsight a mutual cultivation of perceived exotics. He could not understand why in the blood of Christ anybody would come to Italy to work for meager wages, stand in unruly crowds for any public necessity, put up with primitive toilets and cold buildings while 7/8 of his countrymen were hoping, beseeching the pantheon of gods and goddesses, not to mention trying to bribe officials, to be given a chance to emigrate to America. On the other hand, I was trying to get him to come clean about why the Architect would need muscle. I did eventually get him to tell me. Too much, too politically incorrect and knotted for this reminiscence. Also, it did not take long to figure out that Bruno ruled. He knew everything about everybody, knew where everything was, and had the keys to it all.

Which found me about a month later following him into the attic in which Moretti’s archives were stored dustily and endlessly beneath the roof of the 15th-century palazzo, dimly glowing white like the bones in the Catacombs of Palermo. Perched on pedestals of equal height were the plaster castings of the interior spaces of the scores of buildings Moretti had analyzed in the pages of Spazio. Beyond them, beneath the weak yellow light of what appeared to be original Tesla bulbs, were the plaster models, interior and exterior, of every project he had done to date. On subsequent pilgrimages to my Jerusalem, I would come upon pristine, unopened sets of Spazio wrapped by issue, every one of them. So highly regarded was the magazine that the complete sets of issues were listed by the Belle Arte (the national watchdog of the artistic patrimony) as a national treasure and were not to be removed from Italy any longer without official dispensation.

I had to meet, to speak with him. “How,” I asked Bruno, “can this be done?”

“I really am sorry, Aidala, the architect has been traveling and has been very busy. He doesn’t usually meet with the colleagues unless they are assigned on a project directly with him. You have not been assigned as yet to a particular project and so don’t really have a reason. However, I’ll see if a way can be arranged or presents itself.”

Together we came upon a ploy for me to gain entrance to the Cathedral. I was to do some piece of work uniquely of the studio and at once mine that would catch Moretti’s attention. At the time I was working as a utility draftsman and renderer, filling in on projects where and when needed, usually doing the job in two to four days. I reported to the studio director, who doled out the work to me. I was an arm and hand and eye—brain was not needed. Brainwork was for an assignment to a project.

I was told to do a large presentation rendering of a site development plan for a project called “Appia Antica.” Yes, that one. It was a housing development of individual though clustered villas, priced attractively for deposed monarchy and others of the black aristocracy (which included film stars, singers, and other performers, what we today call “Eurotrash” or, if home raised, “masters of our universe” or celebrities).

The important thing about the project was that it was sited on an outparcel within the newly designated National Park of the Via Appia Antica.

Gardella had asked me if, rather than the buildings delineated as roofs, would I, as she had seen in some U.S. mags, render the ground floor plans. As a bonus, I could use my brain and furnish them, differently of course. The drawings would be used in a presentation that the architect Moretti would be making to the client in a week, so I did not have much time. I was to make the furnishings “chic.”

The client was very important, and a success on Via Appia could lead to an even larger project on a site he owned on the Yugoslavian coast. “Well,” I assured her, “I’ll take care of it.” With a property in a national park, the client was, I thought, probably some deposed monarch or family appended, sent into generous exile by the very grateful sort of democratically elected slate of left-wing thugs who usurped the entitlements of the right-wing thugs of the airless, dying aristocracies of a few countries. Turned out it was King Paul and his wife of whatever that part of Yugoslavia was called before it was torqued and hammered into place by Tito.

I worked my ass off. These were drawings in ink wash and pen on elephant-sized sheets of handmade, 100% cotton paper. I worked day. I worked night. And at the end of each shift thanked Providence I had not knocked over the inkbottle or broken a loaded pen point over a wash.

I finished the drawing early by a couple of days, to allow myself time to settle my affairs before being sent packing by Gardella or who knows what by Bruno.

What I had done was to render each unit’s carpet patterns or furniture shadows or landscaping so that the whole rendered project spelled out ambiguously, but there when looked at just so,

T-O-M-A-I-D-A-L-A-D-R-E-W-T-H-I-S.

(In Italian, of course.)

The studio director, quantity surveyor, and engineer missed it. Bruno the cool saw it. Bruno the non-architect, unblinded by expertise and immune to professional incomprehension that someone would try such a circus stunt, Bruno completely in touch with the creative energies needed for such skullduggery and intrigue carried in the Italian DNA, pointed out to Moretti the expertly crafted and quite beautifully subtle acing of the studio. I had done him proud. “Something outrageous, beautifully crafted, and easily altered, so as not to cause him embarrassment. The Architect likes that sort of thing,” he had suggested.

I was at the open doors; between me and Moretti, who was standing and beckoning me to enter, were the tangle of easels and a path more felt than seen.

Seeing him for the first time was recognizing a familiar. Jesus, I thought, he’s the Fat Man, Nero Wolfe, all 325 pounds of him dazzlingly turned out. He was wearing my yearly salary in clothes that draped about his enormous body, cloth so soft it would never wrinkle. As he sat down smiling, I wondered if he had seen a wrinkle in five years. “Signore Architetto Aidala, welcome please.” Nails buffed, skin firm and glowing, he exuded the inner health of a lack of concern about money. He had rather small hands for a man his size and on his right wore a gold ring embossed with the head of a Roman emperor or governor, said to me later to be an ancestor.

He picked up the brush by the meter-long handle and swirled it around in a pot of water and color on the floor next to him, unnoticed and hidden by the field of schemes that was his desk. I figured out what he was doing. It was then that Bruno appeared. Behind Moretti on the wall was a contraption that held a roll of heavy watercolor paper vertically, which Bruno, by turning a crank, caused to unroll and slide horizontally to the left. The paper was held in the contraption about eighteen inches behind Moretti. The bottom of the paper was at the level of Moretti’s seated shoulders and the top about four feet above that.

Leaning left to right across his amplitude, mixing at his floor palette, he said, “Architetto Aidala, the very first instantaneous impression you have of any object seen against a background, especially the sky, is the silhouette. The plans juxtaposed against the sky and terrain from the approach road lead me to concluding the silhouette of the roof edge of the first group of villas should look like this.” He lifted his arm and brush from left to right, turning his body over his right shoulder and either painted or the line leapt off the fully loaded brush onto the paper as lightning would. Thirty-plus years later, watching Montana throw that line to Dwight Clark that one time or Jerry Rice often, I would recognize the same lightning strike. That line going backward to his right over his shoulder was, I found out at my desk later, utterly accurate. Each zigzag break coincided with what I had been drawing for a week. It was, in retrospect, forty-plus years later, the best, truest, most accurate, shocking, brilliantly dazzling line I ever saw anybody draw except for Montana and Rice, and it took two of them. That line was drawn in less time than it took Montana to backpedal, and Moretti did it all by himself like Ginger, backwards.

I recognized and knew the power of a line as the contour of an idea, and it changed my life.

I shit you not.

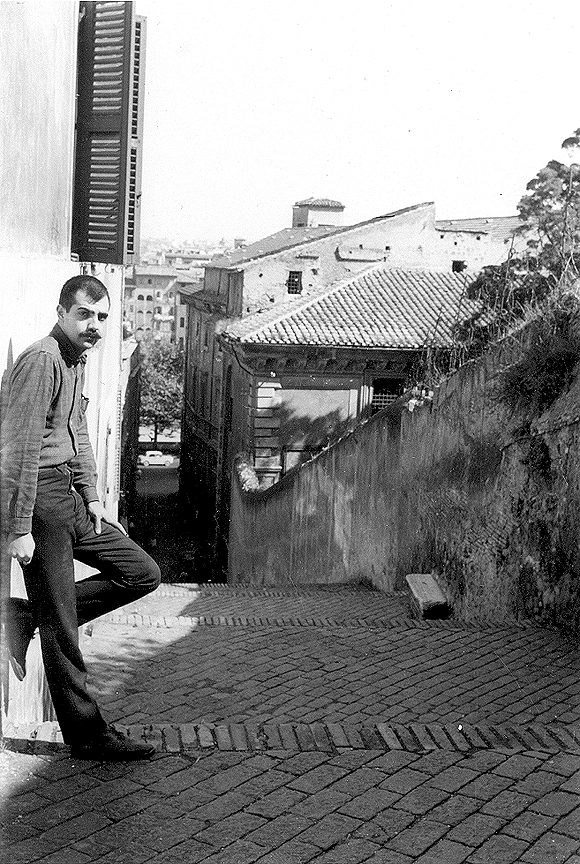

Author Thomas R. Aidala, FAIA (pictured as a young man in Rome), provides professional services to both the private and public sectors from his studio in Kelseyville, California. His award-winning work includes Zellerbach Hall at UC Berkeley, and he has set standards for planning and urban design with his projects for communities from St. Helena to Jerusalem. His early work includes three years in Rome working with Luigi Moretti, Walter Gropius, and The Architects Collaborative. More recently, he served as principal architect and urban designer for the San Jose Redevelopment Agency, where he directed the rebuilding of Downtown San Jose. In 1996, he received the AIA’s Thomas Jefferson Award, its highest national honor for design of public architecture.

Originally published 2nd quarter 2003, in arcCA 03.2, “Global Practice.”