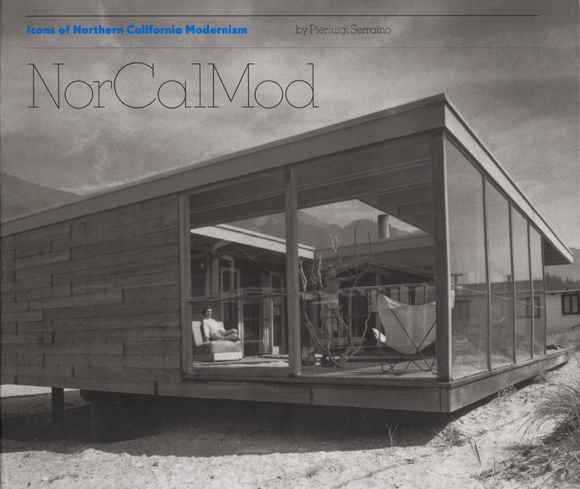

In his Modern Architecture, Kenneth Frampton distinguishes critical regionalism from regionalism as “a spontaneously produced” vernacular. Critical regionalism is intended “to identify those recent regional ‘schools’ whose primary aim has been to reflect and serve the limited constituencies in which they are grounded.” It depends on “a certain prosperity,” he writes, as well as “some kind of anti-centrist consensus, an aspiration at least to some form of cultural, economic, and political independence.” Frampton, like Lewis Mumford before him, counts San Francisco as such a school. A new book by the architect and critic Pierluigi Serraino, NorCalMod, challenges this view.

Interested in California’s mid-twentieth-century modernism and prompted by a suggestion from Elaine Jones to look at the Bay Area, “considered a hotbed of modern architecture in the fifties,” Serraino has written a revisionist history of its postwar period. Along the way, he also discusses the role of architectural photographers and the design press in drawing attention to architects at the periphery of their editorial vision.

Rethinking Bay Regionalism

Serraino argues that the official history of postwar Bay Regionalism distorts the facts by consciously excluding modernism and its Bay Area exponents. In his view, “the evidence reveals an incohesive chorus of voices, if not an atomized design aesthetic, among Northern California architects during this time.” He concludes that,

When all these dots are connected, the picture that emerges is rather different, indeed more comprehensive and richer in design vocabulary than one might expect: Northern California was an unrestrained laboratory for Modern architecture, propelled by the explosion of the national economy. Regionalists and Modernists alike promoted economy of design, but through profoundly different architectural expressions.

In the early eighties, I worked with Joe Esherick on an article in Space & Society on the evolution of his work. In one of our conversations, he said to me that he felt that the steady stream of national and international design magazines made it impossible for architects here to avoid the contamination of larger movements, whatever they might be. Does his comment exemplify the anti-centrism that Frampton believes is characteristic of regional schools?

Yet the “regional” architect who said it shares the status of an outlander with Bernard Maybeck, Chuck Bassett, and Stanley Saitowitz—to name three other of the Bay Area’s leading lights. All four arrived here trained in a larger tradition, and then absorbed what they found here— its history and most of all its sense of place. Esherick was the most directly influenced by older Bay Regional architects, but the work he and his EHDD collaborators produced was as eclectic as Serraino posits. Among the influences: Corbu and Kahn (through Esherick), and MLTW and Rossi (through his gifted partner George Homsey). Homsey, a kind of fifth Beatle to MLTW, influenced them in turn.

In a recent interview in AIA San Francisco’s LINE, architect and publisher Bill Stout notes ruefully that Allan Temko, Bay Regional Modernism’s main polemicist, paid no attention to houses. That omission left William Wurster free to frame the region’s story in his own image. San Francisco Modernism was the province of SOM—something imported. (It’s interesting that Wurster’s contribution to the Bank of America Tower was to look back to Timothy Pflueger for inspiration.) Not every Modernist here fell off the East Coast’s radar, but the story definitely got around.

Architecture and the Media

A practicing architect and independent scholar, Serraino teamed up with Julius Shulman on an earlier book on the work of this iconic photographer of mid-century modernism in Southern California. Not surprisingly, this beautifully illustrated new book is also an excellent primer for architects on how to document their work so historians can find it. This reflects Serraino’s view that only “that which is photographed, reported, and generations later still retrievable can continue to exist in architectural history.” In a maxim worthy of Goethe, he takes this thought a measure further:

Architecture without photographs is like a traveler without a passport: it has no identity as far as the media is concerned. Photography makes architecture noticeable. Also, photography is the oxygen of architecture. It keeps its sister field alive in the present and in the future.

His maxim refers to architects as well as architecture. Indeed, his best example is David Thorne. After designing a widely published modernist house in the Oakland hills for Dave Brubeck, he felt pressured by the resulting media coverage and deliberately slipped under the radar, changing his first name and assiduously keeping himself and his work out of the press. As a result, both “disappeared” until Serraino rediscovered them.

So is it “publish or perish,” even for architects? Serraino is right that it’s important to document and that the choice of a photographer matters in terms of securing coverage. That coverage has its limits, however. The design press is a distorting mirror, both in how it values and reports on contemporary work and the way it credits who did what. It’s also ephemeral, in terms of public consciousness. Houses aren’t the Acropolis, but they are sturdier than magazines, and they have owners. There’s a natural curiosity about their provenance, and of course in the Bay Region’s inflated housing market, provenance has value. Roger Lee may have been invisible nationally, but he’s still a known commodity in the East Bay.

Seeing the Work with New Eyes

The rise of Dwell and the importance now given to mid-century Modernist houses here make a book like Serraino’s, which reassesses the work of earlier decades in light of current tastes, seem almost inevitable. The passage of time also makes it easier to understand how the work of the Bay Regional Modernists differs from their contemporaries and builds imaginatively on Modernist antecedents. At the time, though, East Coast editors may have seen their work as derivative of trends more fully developed elsewhere. L.A., fueled by photographers like Shulman who made the work so sexy, got the attention.

What sets the modernism of the Bay Region apart from everywhere else is the place itself—its dramatic sites, especially for houses, and its remarkable light and climate. It’s not the only place with these characteristics, but they provide our version of mid-century Modernism with its DNA.

One of the best things about NorCalMod is its inclusiveness. Serraino understands how this sense of place links pure exemplars of the International Style, like Donald Olsen, to architects like Roger Lee who are much closer to the ranch house style that is as close as we really get to fifties and sixties vernacular. NorCalMod displays this vividly, drawing on our region’s best postwar architectural photographers.

Serraino’s tenacity in getting these remarkable photos into print is another reason to buy this terrific book—it’s like having your own archive of one of our region’s high points. Looking around, I would say we’re in another, so it’s a kind of love letter from the past to a new generation, with this talented Italian as its messenger. Good reading and timely!

Author John Parman writes for AIA San Francisco’s LINE and other publications.

Originally published 4th quarter 2006 in arcCA 06.4, “The UCs.”