If the recording of my world ever bordered on art, it was in the most casual manner, but a real human experience kept on oozing, dribbling, sprinkling, and sometimes freely flowing onto all kinds of accidental paper, whatever happened to be at hand. No spoken or slowly written word can quite express in the same way this past life, as lived in tiny fractions of time.—Richard J. Neutra, Life and Shape, 19621

In his autobiography Life and Shape, renowned Modernist architect Richard J. Neutra explains that travel sketches were his medium for capturing empathy or “in-feeling” with all he saw and encountered throughout his life.2 A sketchpad or sheaf of drawing paper were standard equipment on every trip Neutra took from his teenage years in Vienna to the end of his life. Through color, line, texture and shape, these graphic images depict many issues that informed Neutra’s architecture: the dominant role of environment over human habitat, the need to create places for human interaction, and the design of objects as cultural signifiers.

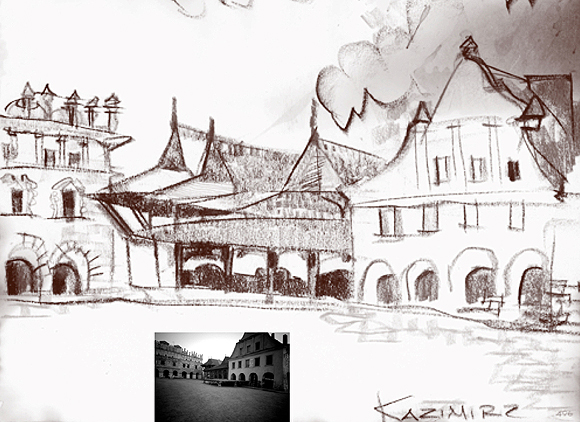

In the College of Environmental Design, California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, we are fortunate to own 106 Neutra travel sketches, made between the late 1940s and the end of the 1960s, just prior to his death in 1970.3 The drawings were donated by architect Dion Neutra, son of Richard and Dione Neutra. A selection of the travel sketches was exhibited at Cal Poly Pomona in 1986, and later at the University of Southern California.

In the small catalog accompanying the Cal Poly exhibition, former Dean Marvin Malecha (who shares Neutra’s passion for the travel sketch), noted that this medium “is far superior to the photograph when perception and understanding are the prime object…The designer can focus on those issues which are most important at the time or those which have made the biggest impression. Distortion, subtraction and even addition are essential to the travel sketch, and they are equally important to the schematic design drawing.”4

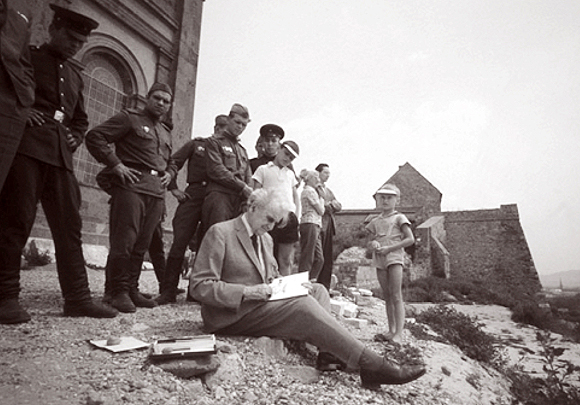

According to Dion Neutra, the act of drawing was a visceral process for his father; through the use of the motor skills required for drawing he became physically engaged with the site. The creation of the travel sketches was a social act for Neutra. It was a chance to connect with people, as is evidenced in a photograph of Neutra surrounded by a group of Russian soldiers, and other onlookers. Dion Neutra believes the travel sketches functioned as a “memory peg” for Neutra, reminding him of what he’d seen and where he’d been.

The early travel sketches, the majority of which are housed in the Richard J. Neutra Collection, Department of Special Collections, UCLA, exhibit the influence of Viennese artists Gustave Klimt and Egon Schiele on the young designer. The significance of drawing of all types was instilled in Neutra’s professional education at the Imperial Institute of Technology in Vienna (which he entered in 1911), followed by his experience in the office of Berlin architect Erich Mendelsohn, the office of Frank Lloyd Wright, and later in collaboration with R.M. Schindler in Los Angeles.

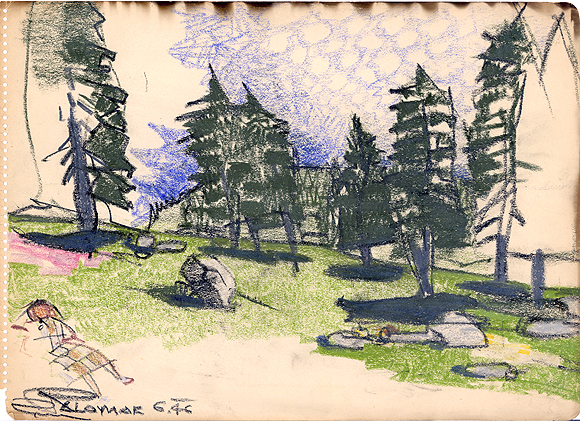

While the majority of the Cal Poly Pomona travel sketches date from the late years of Neutra’s life, the collection contains an earlier drawing of Mt. Palomar, in Southern California (1946). The mood of the drawing is somber: Neutra uses oil crayons to create a dense grouping of pine trees; with the edge of the crayon he crisply outlines boulders strewn in the foreground. As a foil to the sobriety of the scene, Neutra injects a small female figure in the lower left corner; she is tilting on one leg apparently buffeted by the wind that is blowing through the scene. The edges of the sheet are scorched, a reminder of the effect of the devastating fire that destroyed Neutra’s first VDL Studio/Residence in the Silverlake district of Los Angeles in 1963.

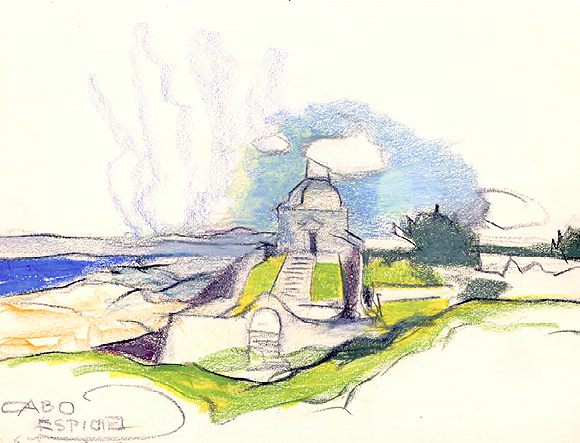

The majority of the Cal Poly Pomona sketches were executed with pastels. Dion Neutra has noted that his father used larger-dimensioned sheets in his later years, which may contribute to the often-expansive character to his images. Neutra chose to depict historically significant sites, yet one never gets the sense of preciousness or self-conscious reverence for his subject. Instead, he extracts, edits, and emphasizes the aspects of the view that interest him.

The drawings tell us about how Neutra literally saw the world. In Life and Shape he explains that his that his left eye had a lens defect and was shortsighted, while his right eye was normal. Over time, the left eye became farsighted, and the other became more normal. He describes the effect of this condition on his visual perception:

Since most of the time I saw and worked with one eye, either the right one for minute sharp detail or the left for over-all composition, my mind similarly also swung back and forth—oscillated, so to speak, between an attempt at total comprehension, an integrated over-all view, and the minute perfectionism of near-sightedness. But I kept using each eye, one imaginatively and wholesale for over-all form, the other more observationally, for tiny, neat detail.5

In his sketch titled “Wetmansherde” (1963), Neutra employs the traditional device of framing his subject through an arched opening. The scene is a grouping of vernacular. The key element of the drawing is a large tree that is planted near the base of the tower. The trunk and branches of the tree extend forward in the scene, its branches sending shock waves around the archway. Spatially the outline of the tree flattens the illusion of three-dimensional space created by the more traditional aspects of the composition. The eye of Neutra transformed the scene into one of considerable artistic interest.

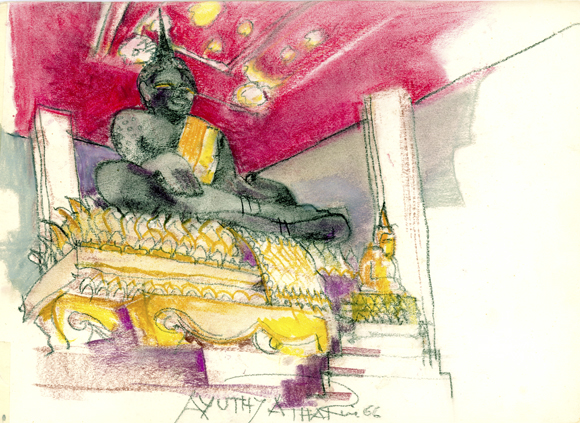

Neutra’s travels took him many points in Asia. A number of the travel sketches depict scenes in Thailand. His sketch of statue of the Buddha in Ayutthaya (1966) is the one the few interior drawings in the Cal Poly Pomona collection. The figure sits on a high throne, its green body contrasting with perspective so that he effectively fills the space near the back of the worship hall. Rather than treat the Buddha with extreme reverence, Neutra chose to capture the bemused expression of the figure as he looks down on his worshipers.

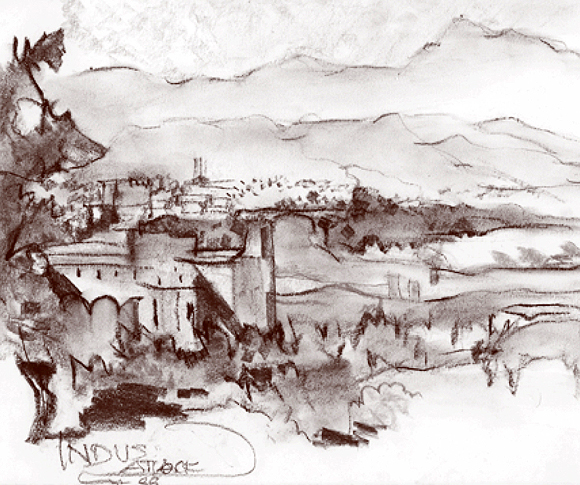

The breadth of Neutra’s vision is clearly evident in his sketch of “Indus. Attock.” (1968). Attock is a town located in the Punjab District of Pakistan. It is reported to have been along the route followed by Alexander the Great in 326 B.C. when he crossed the Hinduskush Mountains to capture the plains beyond the Indus River. The landscape embraces the town—the broad mountain range beyond is softly rendered, as is the vegetation and land—including an oxen in the foreground. The buildings are generalized, with a maroon edge defining an occasional corner or roof. The presence of the river is suggested. The overall effect is one of calmness, with the natural site conditions dominating the scene.

The Neutra travel sketches give us an insight into the great architect’s world. Richard and Dione Neutra traveled the globe at a time when many Euro- the golden throne and the deep red ceiling. Neutra peans and Americans were much more provincial in the range of places they chose to visit. The travel sketches give us an insight into what Neutra saw, and how he saw it. As such, they give us a glimpse into the think and perception of the man, and perhaps his architecture.

1. Richard Neutra. Life and Shape, New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1962, 82.

2. Ibid.

3. The Department of Special Collections, University of California, Los Angeles holds the earlier travel sketches, dating from the 1910s into the 1940s.

4. Marvin J. Malecha. “Introduction. Understanding Architecture through Drawing,” Richard Neutra Travel Sketches, The School of Environmental Design, Cal Poly University, Pomona, 20 October–7 November 1986, n.p.

5. Life and Shape, 73- 74.

6. The slides are housed in the Visual Resources Library, College of Environmental Design, California State Polytechnic University, Pomona.

Author Lauren Weiss Bricker, PhD, is an associate professor of architecture and director of the Archives-Special Collections in the College of Environmental Design, California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. Dr. Bricker is Chair of the State Historical Resources Commission in California and co-chair of the Commission’s Committee on the Cultural Resources of the Modern Age. She is a co-author of the forthcoming Mediterranean Revival House (Abrams), and is currently working on “The Pragmatists,” a study of the American response to the form and ideology of European Modernism, supported by a fellowship from the Clarence S. Stein Institute of Urban and Landscape Studies, Cornell University.

Originally published 3rd quarter 2005 in arcCA 05.3, “Drawn Out.”