Charles M. Davis, FAIA, is a founding partner of EHDD Architecture. In 1978, he undertook the seminal project of his career, the Monterey Bay Aquarium. The project was funded entirely by David and Lucile Packard, who were very involved in the building’s design. Davis talks about this remarkable collaboration and the changing nature of patronage. Interviewer Yosh Asato is a communications consultant and co-editor of LINE, AIA San Francisco’s online journal.

arcCA: The Packard Family and the Monterey Bay Aquarium have been your clients for nearly thirty years. What has this taught you about patronage and architecture?

Davis: We’ve been extremely fortunate with Monterey. The era of just calling up so-and-so because you’re comfortable with them or you’ve worked with them is almost a gone thing. Today it’s about competition.

arcCA: And what do you think is driving that?

Davis: It’s a natural outcome of the amount of information that we have available today. When I started, there were maybe three or four voices in the profession, magazines based in the east, and they gave out the monthly gospel. Now we have arcCA, we have Dwell, we have Wired, and countless online sources. A person who has a reasonable amount of brains will want to look at the array of choices.

arcCA: The Monterey Bay Aquarium was a family endeavor from its earliest moments. What were the implications of this?

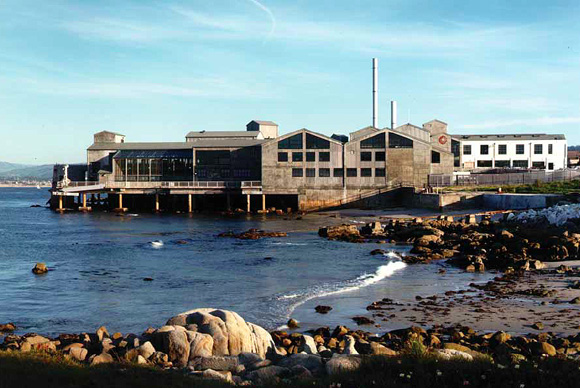

Davis: David Packard was the founder and president of HP for many years, and he had just stepped down. He was looking for something to do. It so happened that two of his daughters, Nancy Burnett and Julie Packard, were marine biologists, and they approached him and his wife with this idea of building an aquarium in Monterey that focused on the marine biology of the Monterey Bay. Packard hired Stanford Research Institute to do a feasibility study, and they said, “Well, if you build a modest aquarium in Cannery Row, you might get a million visitors per year.” That’s how it started. The next thing that happened was a competition. Big table, a lot of people. I was at one end of the table, Mr. Packard was at the other end of the table. It was an hour and a half long interview, and at the end he stood up and said, “When can you go to work?” I was shocked. It was the only time I’ve ever been hired on the spot.

It was on a Wednesday, and the next Monday, I was down in Monterey setting up an office. After two days, he showed up in his red pickup truck and dirty khakis and boots, and I didn’t even notice him. He walked up behind me and said, “Well, I can see you’re doing good here.” I had a Skil saw and tools, and I was making drafting tables. And he said, “Let’s take a walk.”

And I was thinking, “Oh, what the hell is this? I’m just barely getting started and now we’re taking a walk.”

So we walked looking over the Pacific, and he said, “The kids have this idea to do this damn aquarium, and I don’t know whether it’s a good idea or a bad idea. So, my deal with you is going to be this: I’m going to come every Friday to look at what you’ve done. If I like what you’ve done, we’ll work another week. If I don’t like what you’ve done, I’ll pay you off and send you home. Is that a deal?”

arcCA: And his decisiveness set the tone for the entire project?

Davis: He was very imposing; six foot eight and very gruff, an archetypical business tycoon, tough and opinionated. At the same time, I had never been around somebody who could take apart issues or problems and then make good decisions like he could. I’ve always said that if I needed a consultant to help me make ten life or death decisions, it would be David Packard.

So every Friday, he would come in around ten o’clock, and he’d be chatting with his wife, Lucile, or his daughter. Then we’d go into the conference room, and he would become all business, with a set jaw. I would present the results of the last week’s work, and he would ask some questions. And he would also fry me on something. He would jump up and say,

“What the hell is this right here?”

And I would say, “That’s the otter tank.”

And he would ask, “How much does that tank weigh filled with water?”

“Oh, I don’t know. 400,000 pounds.”

“Why in the hell doesn’t it have a column underneath it? If you don’t know anything more about structure than that, we’re going to get somebody else to work on this project.” That’s the kind of guy he was, and he could always tell when he’d really gored you.

But after about an hour, he would calm down a bit and say, “Well, you know, Chuck, I’ve been thinking about the location of the otter tank. It’s out here in this wing, and I understand all this stuff about the storyline and where it fits in the story, but what is Ruth from Duluth going to see when she comes in the front door?”

I would say, “Well, there’s no big exhibit right there right now.”

“Exactly. So I think we ought to put that otter tank over there by the front door.”

“Wow. That’s interesting, that’s a good idea. I’m going to look at that immediately.”

Then we’d go have lunch at a really terrible Chinese restaurant. That was how the project developed, and it’s how the relationships between all of us developed. It was arduous, it was tough, but it was a lot of fun.

By the next meeting, I had moved the otter tank. Of course, the exhibit designers were all fried, because it wasn’t sequential learning and all of that kind of stuff. But there was always a very healthy dialogue between him and his wife, sometimes Julie, sometimes Nancy. And I was taking in everything, and doing what the architect does, which is sift it, grind it, and by the next week we had a response to it.

I was able to withstand the withering ground fire, but I also was able to very slowly earn his respect. He realized that I was working my butt off. I usually would come home on Friday night, do the errands around the house, because I was a bachelor at the time, and then I would drive back in on Sunday and start all over. It was the most intense six months of my career.

I was able to establish a dialogue with him about what the building was going to look like. I think Mrs. Packard thought of the building being much more finished on the inside. But I tried to sell him on the idea that the building would have exposed surfaces and be easy to maintain. We were concerned about leaking pipes and a lot of water flying around overhead. I thought it made good sense that all of that stuff would be organized and exposed, and if you had a problem, you could get to it. Well, he got really excited about that, because he identified that with one of his chip plants.

I got along with him really well, because I had been a general’s aide in the Army, which meant that I shined the boots and got the guy to meetings on time. And so I was used to that sort of authority figure. I always told consultants on the team, “Listen, this guy is not like your dad. He is not like anyone you know. This guy is Mr. Packard, and he is different, and you have to show him respect, or you’ll be history.” And we fired a lot of consultants. We’d call them in, and they’d do their presentation, and he’d say, “Thank you very much, but we don’t need your services anymore, so could you please leave immediately?”

arcCA: Yet your instincts recognized the remarkable potential of this project and this client.

Davis: It was the seminal project in my career, and it did two things for the firm. It convinced people that we could do large projects, and it opened up a whole new dimension of work for us. And, of course, the Monterey Bay Aquarium keeps coming back to us. We did the first expansion, which opened in 1996, and we’re getting ready to do another remodeling of the exhibits.

arcCA: When they did the expansion, was David Packard still involved?

Davis: Not to the same extent, but he would come to board meetings where the progress of the project was presented. Mrs. Packard was very involved in the interiors. She was the leveler, the one who could smooth over the rough edges of the old man. And, no joke, he loved her dearly and he respected her enormously, but there were even sparks between them, because he was a tough dude.

But you have to earn the return gig. Since we started to work on Monterey, whenever Julie Packard or Linda Rhodes or Marty Manson or whoever is involved in Monterey calls, I drop everything and I take care of it. I’ve always put their needs and their interests first and have been very careful to keep my ego in my back pocket, which isn’t the trend nowadays. It’s been almost twenty-nine years, and there’s been huge continuity of people. Six months into the first project, Packard hired Linda Rhodes, who had been working for me, to be his project manager, and we’re grateful that she has since managed all of the aquarium’s major projects. But the organization also has changed, and my organization has changed a bit, too. Now, Marc L’Italien, one of my partners, will carry on and continue to keep the institution happy and contribute to its future quality.

Originally published 1st quarter 2007 in arcCA 07.1, “Patronage.”